It seems like someone is constantly proclaiming the death of email as in this GigaOm article about IT firm Atos Origin planning to stop using email in its internal operations.

GigaOm writer Miguel Valdes Faura points to things like social networking and tools like Salesforce’s Chatter as things that are gradually replacing email.

Look, here’s the thing — the beauty of (most) email is that it is based on an open protocol, SMTP. I have email I sent and received in the late 1980s that I can still read on an email client that was just released yesterday, thanks to the wide support for SMTP.

I’ve also had the same email address for 16 years even though I’ve changed email hosts 6 or 7 times during that period. During a small part of those 16 years, my email was hosted at another company, but for most of the time I’ve owned the server that my email domain ran on. Today, it is dirt cheap for anyone to grab a domain name and a hosting account that includes a mail server.

Social networking and similar systems are largely the antithesis of prevailing state of affairs with email. I can use my Google+, Twitter, Facebook and other accounts only because those companies have decided to continue to allow me to — and their Terms of Service make it clear they can change their mind at any moment and cut me off for pretty much any reason.

On the other hand, if I get fed up with one of my social networks, there’s little I can do but close my account and leave. Since all of these companies use proprietary standards, I can’t easily move my Twitter account to Facebook, much less even consider moving either account to my own webserver.

I can (and do) get my data out of these systems, with varying degrees of difficulty, but just having static copies of the data doesn’t come close to replicating my account. Moreover, most of these systems seem to be getting less open. Twitter, for example, used to make it obvious where the RSS feed for your tweets was, but now they hide it like they’re ashamed of it (or, more likely, can’t figure out how to monetize it).

Every time I read someone write about relying on social networking or closed systems, I always think of the BBC’s Domesday Project — an early attempt at creating a digital artifact in which more than a million people participated. But, of course, the Domesday Project is famous in part because the BBC chose to use a proprietary technology that quickly became obsolete and almost rendered the entire project unreadable.

Social networking, as it is currently constituted, is one giant Domesday Project just waiting to happen.

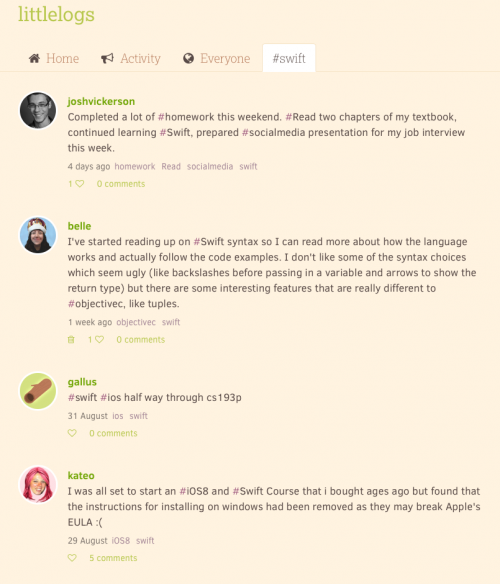

I’ve been playing the open beta of

I’ve been playing the open beta of