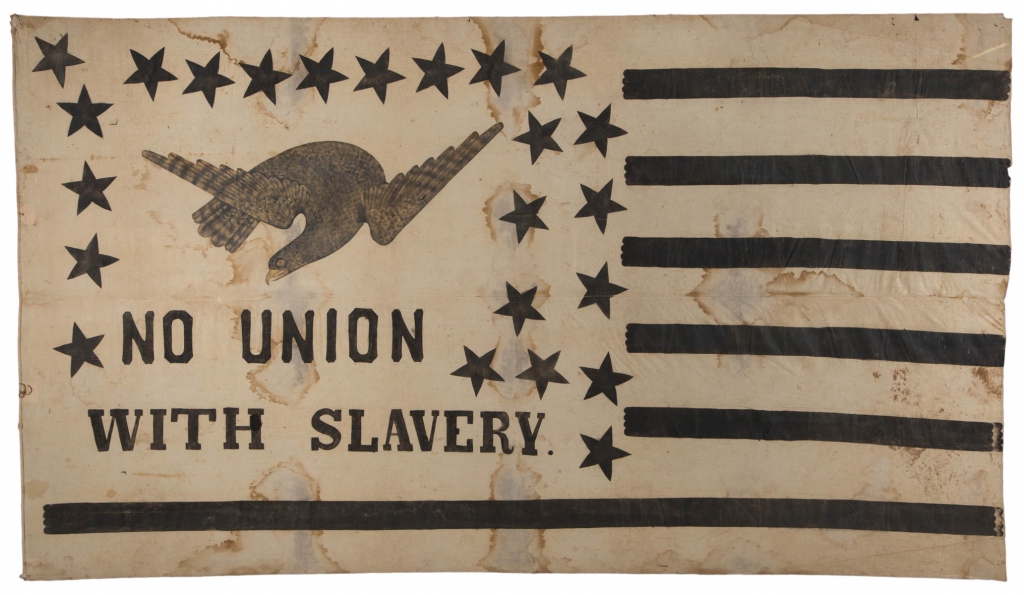

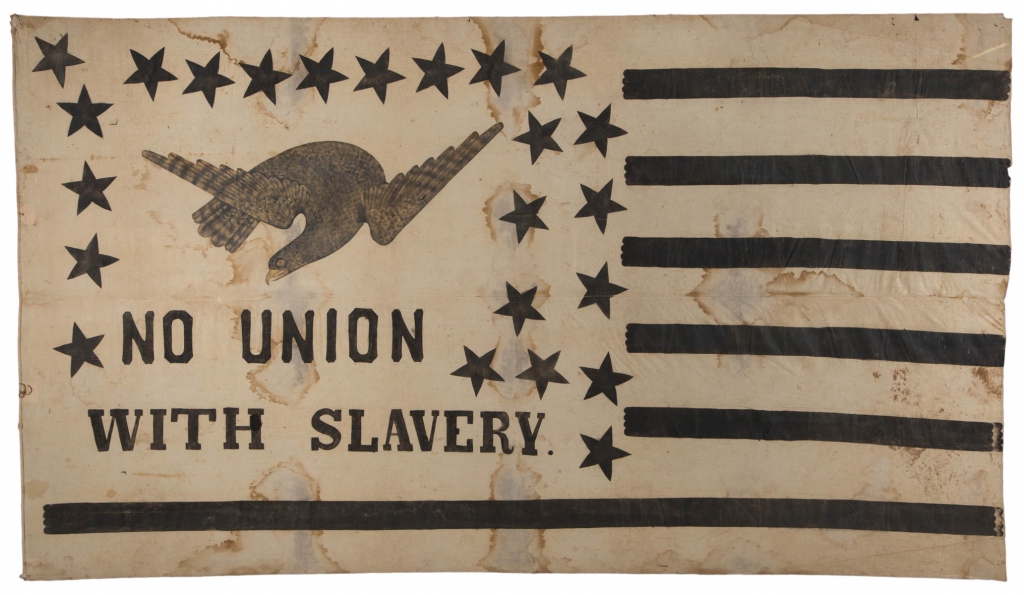

Abolitionist flag from the pre-Civil War era.

Just another nerd.

Abolitionist flag from the pre-Civil War era.

Jourdon Anderson’s letter to his former master, Colonel P. H. Anderson, was published in the Cincinnati Commercial in 1865 and then was reprinted in other newspapers and books.

Dayton, Ohio,

August 7, 1865

To My Old Master, Colonel P.H. Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee

Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again, and see Miss Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.

I want to know particularly what the good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,—the folks call her Mrs. Anderson,—and the children—Milly, Jane, and Grundy—go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated. Sometimes we overhear others saying, “Them colored people were slaves” down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they hear such remarks; but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to Colonel Anderson. Many darkeys would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you master. Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars. Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq., Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense. Here I draw my wages every Saturday night; but in Tennessee there was never any pay-day for the negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter, please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up, and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve—and die, if it come to that—than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters. You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood. The great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

From your old servant,

Jourdon Anderson.

Henry Ward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, had an outsized influence on American religion and politics of the 19th century, but this tidbit from Wikipedia about his activity as an abolitionist is fascinating,

During the pre-Civil-War conflict in the Kansas Territory, known as “Bloody Kansas”, Beecher raised funds to send Sharps rifles to abolitionist forces, stating that the weapons would do more good than “a hundred Bibles”. The press subsequently nicknamed the weapons “Beecher’s Bibles”. Beecher became widely hated in the American South for his abolitionist actions and received numerous death threats.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database collects,

information on almost 36,000 slaving voyages that forcibly embarked over 10 million Africans for transport to the Americas between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. The actual number is estimated to have been as high as 12.5 million. The database and the separate estimates interface offer researchers, students and the general public a chance to rediscover the reality of one of the largest forced movements of peoples in world history.

It has a sister site, African Origins, which has compiled “the personal details of 91,491 Africans liberated by International Courts of Mixed Commission and British Vice Admiralty Courts.” For example, the entry on Barkan notes a 13-year-old boy by that name,

In 1845 an international court located in Freetown, Sierra Leone liberated Barkan a male of 13 years. He was on board the slaving vessel Uncas, which departed from the port of Cabinda before being intercepted and taken to Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Fascinating use of modern technologies to explorer and illuminate old crimes.

JohnHorse.Com is an extensive, but ultimately frustrating, look at the role that rebellious plantation slaves played in the Second Seminole War. Bird claims that by April 1836, almost 400 slaves had “defected to the Seminoles.”

The site’s author, J.B. Bird, argues that professional historians have largely ignored the large number of slaves who left their plantation to join the Seminoles in fighting against white plantation owners due to a bias toward diminishing acts of resistance by slaves. He doesn’t, however, provide any sort of critical look at traditional historian’s view of the role of black slaves in the Second Seminole War, so we’re left taking his word for it.

Frankly, although the site has some interesting information, the thing it is being noticed and praised for widely is the same thing that I found extraordinarily annoying — the site breaks up this extensive information about John Horse, the Seminoles, and plantation slaves into 400 small chunks of information Power Point style. That pretty much kills the narrative flow and makes it difficult to follow Bird’s argument as a whole.

Its a shame he doesn’t have the full text of his chunked-up thesis on the Seminoles available somewhere on his site for those who want more than the slideshow version of his research.

King Lepold’s Ghost

King Lepold’s Ghost

By Adam Hochschild

Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost is a gripping account of a murder mystery — a mystery made all the more horrific because it involves an estimated 10 million victims. Hochschild’s short book is simply one of the most powerful indictments of mass murder ever written, as well as a testament to how much influence even a single person acting on moral outrage over such an event can have.

The murderer, of course, was Belgium’s King Leopold I. Leopold was never satisfied with ruling the meager kingdom of Belgium, especially since his power was strongly circumscribed by an independent legislature. In the 1870s, Leopold began looking to Africa for a colony that would be his alone to rule — that colony turned out to be the Congo.

Using a cleverly run public relations campaign that asserted he simply wanted the Congo to bring civilization to the area and rid the Congo of Arab slave traders, Leopold used Henry Morton Stanley (the journalist famous for tracking down David Livingstone) to negotiate treaties granting Leopold control over the Congo. That most of the African leaders Stanley signed treaties with either did not have the authority to sign such treaties or did not understand what they were signing was of little consequence to either Stanley or Leopold.

Of course the treaties did not mean anything without recognition from other world powers and here, sadly, the United States played a crucial role in legitimizing Leopold’s control of the Congo. In 1884, driven by Leopold’s promise of free trade in the Congo (which would never actually happen), the United States became the first country to recognize Leopold’s claim over the colony and Leopold successfully maneuvered other countries into recognizing his claims as well.

And it was literally Leopold’s claim. Fearful of being saddled with any debt from the venture, the Belgium legislature had insisted on an agreement with Leopold that he would be solely responsible for the Congo — and, of course, be the sole source of power.

Far from discouraging slavery, however, Hochschild makes clear that Leopold turned the Congo into a virtual slave state that rivaled Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Russia for the sheer level of barbarity. As with most acts of mass murder, the catalog of cruelties Hochschild’s documents are so extensive and frequent that the sheer repetition of the whole tends to numb the senses. This apparently afflicted those who administered and profited from the Congo — cruelty and torture were such an everyday part of life, they were hardly regarded as exceptional by soldiers, merchants and others.

An example that gets to the core of what Leopold’s Congo was about, however, is the matter of the severed hands. Natives required to perform labor were often reluctant to do so, and the Congo used a time honored method of forcing their compliance — they armed competing tribes and individuals and charged them with keeping the workers in line. There was a concern, however, that the native enforcers were trigger happy and wasted ammunition or used the guns they had been supplied with for hunting wild game. So after awhile they were charged with proving the bullets they used were really used to kill their fellow AFricans. Specifically, for every bullet they expended, they were expected to provide the severed hand of the victim.

Hochschild writes of the Rev. William Sheppard, a missionary who wrote about the grisly scenes he witnessed traveling across the Congo, including this scene,

In 1899 the reluctant Sheppard was ordered by his superiors to travel into the bush, at some risk to himself, to investigate the source of the fighting. There he found bloodstained ground, destroyed villages, and many bodies; the air was thick with the stench of rotting flesh. On the day he reached the marauders’ camp, his eye was caught by a large number of objects being smoked. The chief “conducted us to a framework of sticks, under which was burning a slow fire, and there they were, the right hands, I counted them, 81 in all.” The chief told Sheppard, “Se! Here is our evidence. I always have to cut off the right hands of those we kill in order to show the State how many we have killed.” He proudly showed Sheppard some of the bodies the hands had come from. The smoking preserved the hands in the hot, moist climate, for it might be days or weeks before the chief could display them to the proper official and receive credit for his kills.

Despite Sheppard’s accounts and the accounts of others, it was not until E.D. Morel took up the Congo’s cause that the horrors of what were happening in the Congo became widely known. Morel was an employee of a Belgium company that handled shipments to and from the Congo. Morel noticed that not only did the shipments he was seeing not match official Congo trade statistics, but that while ship after ship arrived from the Congo filled with rubber and other goods, the only thing that ever departed from Belgium were ships filled with weapons. The conclusion was obvious to Morel — there was no trade between the Congo and Belgium as Leopold and his agents claimed. As Morel later put it, “I was giddy and appalled at the cumulative significance of my discoveries. It must be bad enough to stumble upon a murder. I had stumbled upon a secret society of murderers with a King for a croniman.”

Morel, more than anyone else, was responsible for finally shining a light on the true nature of Leopold’s Congo in what Hochschild rightly describes as the first human rights campaign of the 20th century. Only seven years after Morel began his campaign against Leopold, the King was forced to sell the colony to the government of Belgium which took on the job of administering the colony.

Unfortunately, the story of the Congo does not have a happy ending. While many people saw Leopold’s sale as a victory — even Morel finally conceded victory in 1913 as interest in the Congo was waning — Hochschild makes clear that all that really changed was appearances.

World War I drove the Congo issue completely out of the papers, and Morel was slandered due to his anti-war stance. The Belgian government the outward trappings of forced labor, but simply turned to confiscatory taxation to accomplish the same thing. Brutalization of natives using the lash and other techniques continued in full force. Even the vestiges of an especially cruel system of state-sanctioned hostage taking remained in place, though covered in different finery and bureaucratic language.

More importantly, both the history and the lesson of the COngo were largely forgotten. Hochschild writes that although Belgium is home to the largest museum of Africana in the Western world, there is not a single mention of what happened in the Congo in that museum. Official state records that documented the horrors in the Congo were still marked as secret until just a couple decades ago, and have still been seen by only a handful of independent researchers.

The Congo received its independence in 1960. The United States and Belgium conspired together to overthrow the only democratically elected leader of that nation — Patrice Lumumba was murdered in January 1961 less than two months after being named the Congo’s prime minister. In his place, the United States gave more than $1 billion in aid to dictator Joseph Desire Mobutu, who was overthrown in 1997 by another dictator, Laurent Kabila, who himself was assassinated just a few years later.

Still, Hochschild argues that Morel and his movement accomplished two things. First, they created an extensive historical record that will never allow future generations to misunderstand just how horrific Leopold’s Congo was. Second,

The movement’s other great achievement is this. Among its supporters, it kept alive a tradition, a way of seeing the world, a human capacity for outrage at pain inflicted on someone of another color, in another country, at the end of the earth.

For his part, Hochschild has written an account that follows in the best tradition of that movement.