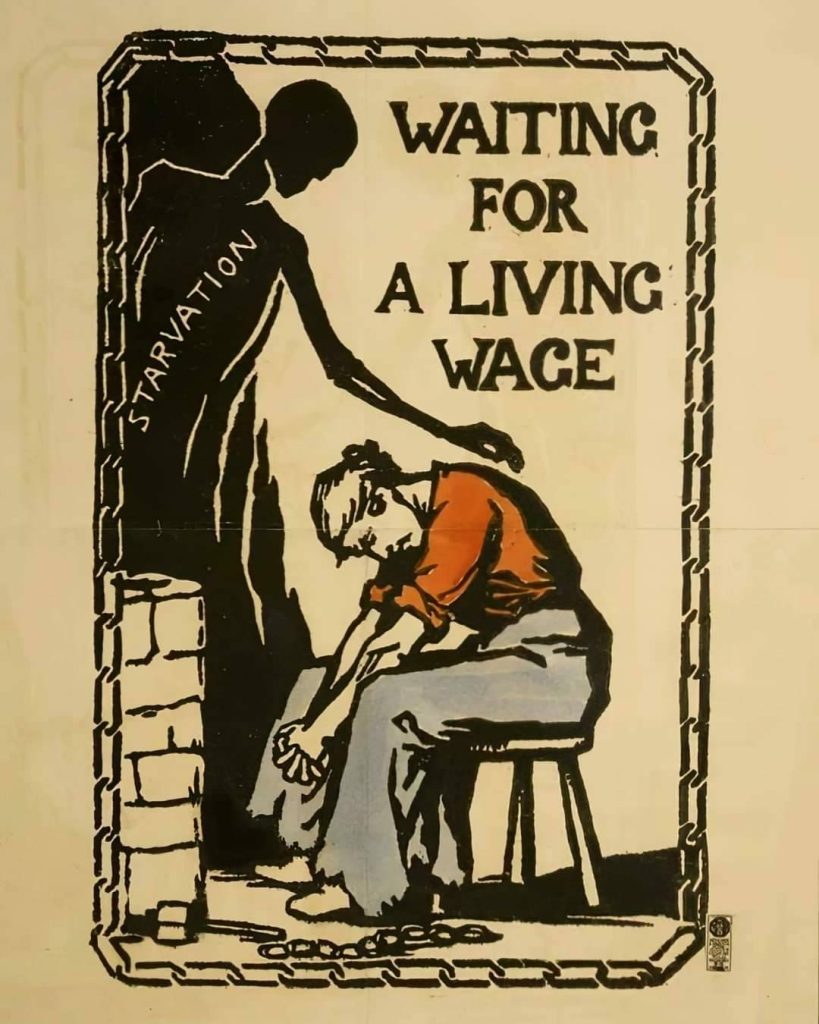

Union supporters distributed this poster during the 1910 Cradley Heath Chain Makers’ Strike in Great Britain.

At the start of the 20th century the campaign to end the exploitation of “sweated” labour gained increasing popular support. In 1909 the Liberal government passed the Trade Boards Act to set up regulatory boards to establish and enforce minimum rates of pay for workers in four of the most exploited industries – chain-making, box-making, lace-making and the production of ready-made clothing. In the Spring of 1910, the Chain Trade Board announced a minimum wage for hand-hammered chain-workers of two and a half pence an hour – for many women this was nearly double the existing rate. At the end of the Trade Board’s consultation period in August 1910, many employers refused to pay the increase. In response, the women’s union, the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW), called a strike.

The strike lasted 10 weeks and attracted immense popular support from all sections of society – nearly £4,000 of donations were received by the end of the dispute from individual workers, trade unions, politicians, members of the aristocracy, business community and the clergy. The founder of the NFWW, Mary Macarthur, used mass meetings and the media – including the new medium of cinema – to bring the situation of the striking women to a wider audience and the strike became an international cause célèbre. Within a month 60% of employers had signed the ‘White List’ and agreed to pay the minimum rate, the dispute finally ended on 22 October when the last employer signed the list.