SIX MONTHS IN MEXICO

BY

NELLIE BLY

AUTHOR OF "TEN DAYS IN A MAD HOUSE," ETC., ETC.

NEW YORK

AMERICAN PUBLISHERS CORPORATION

1888

TO

GEORGE A. MADDEN,

MANAGING EDITOR

OF THE

PITTSBURG DISPATCH,

IN REMEMBRANCE OF HIS NEVER-FAILING KINDNESS

JAN. 1st, 1888.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I.

ADIEU TO THE UNITED STATES.

One wintry night I bade my few journalistic friends adieu, and, accompanied by my mother, started on my way to Mexico. Only a few months previous I had become a newspaper woman. I was too impatient to work along at the usual duties assigned women on newspapers, so I conceived the idea of going away as a correspondent.

Three days after leaving Pittsburgh we awoke one morning to find ourselves in the lap of summer. For a moment it seemed a dream. When the porter had made up our bunks the evening previous, the surrounding country had been covered with a snowy blanket. When we awoke the trees were in leaf and the balmy breeze mocked our wraps.

Three days, from dawn until dark, we sat at the end of the car inhaling the perfume of the flowers and enjoying the glorious Western sights so rich in originality. For the first time I saw women plowing while their lords and masters sat on a fence smoking. I never longed for anything so much as I did to shove those lazy fellows off.

After we got further south they had no fences. I was glad of it, because they do not look well ornamented with lazy men.

The land was so beautiful. We gazed in wonder on the cotton-fields, which looked, when moved by the breezes, like huge, foaming breakers in their mad rush for the shore. And the cowboys! I shall never forget the first real, live cowboy I saw on the plains. The train was moving at a "putting-in-time" pace, as we came up to two horsemen. They wore immense sombreros, huge spurs, and had lassos hanging to the side of their saddles. I knew they were cowboys, so, jerking off a red scarf I waved it to them.

I was not quite sure how they would respond. From the thrilling and wicked stories I had read, I fancied they might begin shooting at me as quickly as anything else. However, I was surprised and delighted to see them lift their sombreros, in a manner not excelled by a New York exquisite, and urge their horses into a mad run after us.

Such a ride! The feet of the horses never seemed to touch the ground. By this time nearly all the passengers were watching the race between horse and steam. At last we gradually left them behind. I waved my scarf sadly in farewell, and they responded with their sombreros. I never felt as much reluctance for leaving a man behind as I did to leave those cowboys.

The people at the different stopping-places looked at us with as much enjoyment as we gazed on them. They were not in the least backward about asking questions or making remarks. One woman came up to me with a smile, and said:

"Good-mornin', missis; and why are you sittin' out thar, when thar is such a nice cabin to be in?"

She could not understand how I could prefer seeing the country to sitting in a Pullman.

I had imagined that the West was a land of beef and cream; I soon learned my mistake, much to my dismay. It was almost an impossibility to get aught else than salt meat, and cream was like the stars—out of reach.

It was with regret we learned just before retiring on the evening of our third day out from St. Louis, that morning would find us in El Paso. I cannot say what hour it was when the porter called us to dress, that the train would soon reach its destination. How I did wish I had remained at home, as I rubbed my eyes and tried to dress on my knees in the berth.

"It's so dark," said my mother, as she parted the curtains. "What shall we do when we arrive?"

"Well, I'm glad it's dark, because I won't have to button my boots or comb my hair," I replied, laughing to cheer her up.

I did not feel as cheerful as I talked when we left the train. It had been our home for three days, and now we were cast forth in a strange city in the dark. The train employés were running about with their lanterns on their arms, but no one paid any attention to the drowsy passengers.

There were no cabs or cabmen, or even wheelbarrows around, and the darkness prevented us from getting a view of our surroundings.

"This has taught me a lesson. I shall fall into the arms of the first man who mentions marry to me," I said to my mother as we wended our way through freight and baggage to the waiting-room, "then I will have some one to look after me."

She looked at me with a little doubting smile, and gave my arm a reassuring pressure.

I shall never forget the sight of that waiting-room. Men, women, and children, dogs and baggage, in one promiscuous mass. The dim light of an oil-lamp fell with dreary effect on the scene. Some were sleeping, lost for awhile to all the cares of life; some were eating; some were smoking, and a group of men were passing around a bottle occasionally as they dealt out a greasy pack of cards.

It was evident that we could not wait the glimpse of dawn 'mid these surroundings. With my mother's arm still tightly clasped in mine, we again sought the outer darkness. I saw a man with a lantern on his arm, and went to him and asked directions to a hotel. He replied that they were all closed at this hour, but if I could be satisfied with a second-class house, he would conduct us to where he lived. We were only too glad for any shelter, so without one thought of where he might take us, we followed the light of his lantern as he went ahead.

It was only a short walk through the sandy streets to the place. There was one room unoccupied, and we gladly paid for it, and by the aid of a tallow candle found our way to bed.

CHAPTER II.

EL PASO DEL NORTE.

"My dear child, do you feel rested enough?" I heard my mother ask.

"Are you up already?" I asked, turning on my side, to see her as she sat, dressed, by the open window, through which came a lazy, southern breeze.

"This hour," she replied, smiling at me; "you slept so well, I did not want to rouse you, but the morning is perfect and I want you to share its beauties with me."

The remembrance of our midnight arrival faded like a bad nightmare, and I was soon happy that I was there; only at mealtime did I long for home.

We learned that the first train we could get for Mexico would be about six o'clock in the afternoon, so we decided "to do" the town in the meanwhile.

El Paso, which is Spanish for "The Pass," is rather a lively town. It has been foretold that it will be a second Denver, so rapid is its growth. A number of different railway lines center here, and the hotels are filled the year round with health and pleasure seekers of all descriptions. While it is always warm, yet its climate is so perfect that it benefits almost any sufferer. The hotels are quite modern, both in finish and price, and the hack-drivers on a par with those in the East.

The prices for everything are something dreadful to contemplate. The houses are mostly modern, with here and there the adobe huts which once marked this border. The courthouse and jail combined is a fine brick structure that any large city might boast of. Several very pretty little gardens brighten up the town with their green, velvety grasses and tropical plants and trees. The only objection I found to El Paso was its utter lack of grass.

The people of position are mainly those who are there for their health, or to enjoy the winter in the balmy climate, or the families of men who own ranches in Texas. The chief pleasure is driving and riding, and the display during the driving hour would put to shame many Eastern cities. The citizens are perfectly free. They speak and do and think as they please.

In our walks around we had many proffer us information, and even ask permission to escort us to points of interest.

A woman offered to show us a place where we could get good food, and when she learned that we were leaving that evening for the City of Mexico, she urged us to get a basket of food. She said no eating-cars were run on that trip, and the eating gotten along the way would be worse than Americans could endure. We afterward felt thankful that we followed her advice.

El Paso, the American town, and El Paso del Norte (the pass to the north), the Mexican town, are separated, as New York from Brooklyn, as Pittsburgh from Allegheny. The Rio Grande, running swiftly between its low banks, its waves muddy and angry, or sometimes so low and still that one would think it had fallen asleep from too long duty, divides the two towns.

Communication is open between them by a ferryboat, which will carry you across for two and one half cents, by hack, buggies, and saddle horses, by the Mexican Central Railway, which transports its passengers from one town to the other, and a street-car line, the only international street-car line in the world, for which it has to thank Texas capitalists.

It is not possible to find a greater contrast than these two cities form, side by side. El Paso is a progressive, lively, American town; El Paso del Norte is as far back in the Middle Ages, and as slow as it was when the first adobe hut was executed in 1680. It is rich with grass and shade trees, while El Paso is as spare of grass as a twenty-year old youth is of beard.

On that side they raise the finest grapes and sell the most exquisite wine that ever passed mortals' lips. On this side they raise vegetables and smuggle the wine over. The tobacco is pronounced unequaled, and the American pockets will carry a good deal every trip, but the Mexican is just as smart in paying visits and carrying back what can be only gotten at double the price on his side; but the Mexican custom-house officials are the least exacting in the world, and contrast as markedly with the United States' officials as the two towns do one to the other.

One of the special attractions of El Paso del Norte (barring the tobacco and wine) is a queer old stone church, which is said to be nearly 300 years old. It is low and dark and filled with peculiar paintings and funnily dressed images.

The old town seems to look with proud contempt on civilization and progress, and the little padre preaches against free schools and tells his poor, ignorant followers to beware of the hurry and worry of the Americans—to live as their grand- and great-grandfathers did. So, in obedience they keep on praying and attending mass, sleeping, smoking their cigarettes and eating frijoles (beans), lazily wondering why Americans cannot learn their wise way of enjoying life.

One can hardly believe that Americanism is separated from them only by a stream. If they were thousands of miles apart they could not be more unlike. There smallpox holds undisputed sway in the dirty streets, and, in the name of religion, vaccination is denounced; there Mexican convict-soldiers are flogged until the American's heart burns to wipe out the whole colony; there fiestes and Sundays are celebrated by the most inhuman cock-fights and bull-fights, and monte games of all descriptions. The bull-fights celebrated on the border are the most inhuman I have seen in all of Mexico. The horns of the toros (bulls) are sawed off so that they are sensitive and can make but little attempt at defense, which is attended with extreme pain. They are tortured until, sinking from pain and fatigue, they are dispatched by the butcher.

El Paso del Norte boasts of a real Mexican prison. It is a long, one-storied adobe building, situated quite handy to the main plaza, and within hearing of the merry-making of the town. There are no cells, but a few adobe rooms and a long court, where the prisoners talk together and with the guards, and count the time as it laggingly slips away. They very often play cards and smoke cigarettes. Around this prison is a line of soldiers. It is utterly impossible to cross it without detection.

Mexican keepers are not at all particular that the prisoners are fed every day. An American, at the hands of the Mexican authorities, suffers all the tortures that some preachers delight to tell us some human beings will find in the world to come.

Fire and brimstone! It is nothing to the torments of an American prisoner in a Mexican jail. Two meals, not enough to sustain life in a sick cat, must suffice him for an entire week. There are no beds, and not even water. Prisoners also have the not very comfortable knowledge that, if they get too troublesome, the keepers have a nasty habit of making them stand up and be shot in the back. The reports made out in these cases are "shot while trying to escape."

In the afternoon I exchanged my money for Mexican coin, getting a premium of twelve cents on every dollar. I had a lunch prepared, and as the shades of night began to envelop the town, we boarded the train for Mexico. After we crossed the Rio Grande our baggage was examined by the custom-house officers while we ate supper at a restaurant which, strangely enough, was run by Chinamen. This gave us a foretaste of Mexican food and price.

It was totally dark when we entered the car again, and we were quite ready to retire. There were but two other passengers in the car with us. One was a Mexican and the other a young man from Chicago.

We soon bade them good-night, and retired to our berths to sleep while the train bore us swiftly through the darkness to our destination.

CHAPTER III.

ALONG THE ROUTE.

"Thirty minutes to dress for breakfast," was our good-morning in Mexico. We had fallen asleep the night previous as easily as a babe in its crib, with an eager anticipation of the morrow. Almost before the Pullman porter had ceased his calling, our window shades were hoisted and we were trying to see all of Mexico at one glance.

That glance brought disappointment. The land, almost as far as the eye could carry, which is a wonderful distance in the clear atmosphere of Mexico, was perfectly level. Barring the cacti, with which the country abounds, the ground was bare.

"And this is sunny Mexico, the land of the gods!" I exclaimed, in disgust.

By the time we had completed our toilet the train stopped, and we were told to got off if we wanted any breakfast. We followed our porter to a side track where, in an old freight car, was breakfast. We climbed up the high steps, paying our dollar as we entered, and found for ourselves places at the long table. It was surrounded by hungry people intent only on helping themselves. Everything was on the table, even to the coffee.

I made an effort to eat. It was impossible. My mother succeeded no better.

"Are you not glad we brought a lunch?" she asked, as her eyes met mine.

We went back to the car and managed to make a tolerable breakfast on the cold chicken and other eatables we found in our basket.

But the weather! It was simply perfect, and we soon forgot little annoyances in our enjoyment of it. We got camp chairs, and from morning until night we occupied the rear platform.

As we got further South the land grew more interesting. We gazed in wonder at the groves of cacti which raised their heads many feet in the air, and topped them off with one of the most exquisite blossoms I have ever seen.

At every station we obtained views of the Mexicans. As the train drew in, the natives, of whom the majority still retain the fashion of Adam, minus fig leaves, would rush up and gaze on the travelers in breathless wonder, and continue to look after the train as if it was the one event of their lives.

As we came to larger towns we could see armed horsemen riding at a 2:09 speed, leaving a cloud of dust in their wake, to the stations. When the train stopped they formed in a decorous line before it, and so remained until the train started again on its journey. I learned that they were a government guard. They do this so, if there is any trouble on the train or any raised at the station during their stop, they could quell it.

Hucksters and beggars constitute most of the crowd that welcomes the train. From the former we bought flowers, native fruit, eggs, goat milk, and strange Mexican food. The pear cacti, which is nursed in greenhouses in the States, grows wild on the plains to a height of twenty feet, and its great green lobes, or leaves, covered thickly with thorns, are frequently three feet in diameter. Some kinds bear a blood-red fruit, and others yellow. When gathered they are in a thorny shell. The Mexican Indians gather them and peel them and sell them to travelers for six cents a dozen. It is called "tuna," and is considered very healthy. It has a very cool and pleasing taste.

From this century-plant, or cacti, the Mexicans make their beer, which they call pulque (pronounced polke). It is also used by the natives to fence in their mud houses, and forms a most picturesque and impassable surrounding.

The Indians seem cleanly enough, despite all that's been said to the contrary. Along the gutters by the railroad, they could be seen washing their few bits of wearing apparel, and bathing. Many of their homes are but holes in the ground, with a straw roof. The smoke creeps out from the doorway all day, and at night the family sleep in the ashes. They seldom lie down, but sleep sitting up like a tailor, strange to say, but they never nod nor fall over.

The whirlwinds, or sand spouts, form very pretty pictures on the barren plain. They run to the height of one thousand feet, and travel along the road at a 2:04 gait, going up the mountain side as majestic as a queen. But then their race is run, for the moment they begin to descend their spell is broken, and they fall to earth again to become only common sand, and be trod by the bare, brown feet of the Indian, and the dainty hoofs of the burro.

Some one told me that when a man sees a sand spout advancing, and he does not want to be cornered by it, he shoots into it and it immediately falls. I can't say how true it is, but it seems very probable.

We had not many passengers, but what we had, excepting my mother and myself, were all men. They all carried lunch-baskets. Among them was one young Mexican gentleman who had spent several years in Europe, where he had studied the English language. He was very attentive to us, and taught me a good deal of Spanish. He had been away long enough to learn that the Mexicans had very strange ideas, and he quite enjoyed telling incidents about them.

"When the Mexican Railway was being built," he said, "wheelbarrows were imported for the native laborers. They had never seen the like before, so they filled them with earth, and, putting them on their backs, walked off to the place of deposit. It was a long time before they could be made to understand how to use them, and even then, as the Mexicans are very weak in the arms, little work could be accomplished with them.

"You would hardly believe it," he continued, "but at first the trains were regarded as the devil and the passengers as his workers. Once a settlement of natives decided to overpower the devil. They took one of their most sacred and powerful saints and placed it in the center of the track. On their knees, with great faith, they watched the advance of the train, feeling sure the saint would cause it to stop forever in its endless course. The engineer, who had not much reverence for that particular saint or saints in general, struck it with full force. That saint's reign was ended. Since then they are allowed to remain in their accustomed nooks in the churches, while the natives still have the same faith in their powers, but are not anxious to test them."

"Come, I want you to see the strangest mountain in the world," interrupted the conductor at this moment.

We followed him to the rear platform and there looked curiously at the mountain he pointed out. It rose, clear and alone, from the barren plains, like a nose on one's face. It seemed to be of brown earth, but it contained not the least sign of vegetation. It looked as high as the Brooklyn bridge from the water to top, and was about the same length, in an oblong shape. It was perfectly straight across the top.

"When this railroad was being built," he explained, "I went with a party of engineers in search of something new. Through curiosity alone, to get a good view of the land, we decided to climb that strange looking mountain. From here you can not see the vegetation, but it is covered with a low, brown shrub. Can you imagine our surprise when we got to the top to find it was a mammoth basin? Yes, that hill holds in it the most beautiful lake I ever saw."

"That seems most wonderful!" I exclaimed, rather dubiously.

"It is not more wonderful than thousands of other places in Mexico," he replied. "In the State of Chihuahua[1] is a Laguna, in which the water is as clear as crystal. When the Americans who were superintending the work on the railway found it, they decided to have a nice bath. It had been many days since they had seen any more water than would quench their thirst—in coffee, of course. Accordingly, some dozen or more doffed their clothing and went in. Their pleasure was short-lived, for their bodies began to burn and smart, and they came out looking like scalding pigs. The water is strongly alkaline; the fish in the lake are said to be white, even to their eyes; they are unfit to eat."

I give his stories for what they are worth; I did not investigate to prove their truth.

"We do not think much of the people who come here to write us up," the conductor said one day, "for they never tell the truth. One woman who came down here to make herself famous pressed me one day for a story. I told her that out in the country the natives roasted whole hogs, heads and all, without cleaning, and so served them on the table. She jotted it down as a rare item."

"If you tell strangers untruths about your own land can you complain, then, that the same strangers misrepresent it?" asked my little mother, quietly.

The conductor flushed, and said he had not thought of it in that light before.

While yet a day's travel distant from the City of Mexico, tomatoes and strawberries were procurable. It was January. The venders were quite up to the tricks of the hucksters in the States. In a small basket they place cabbage leaves and two or three pebbles to give weight; then the top is covered with strawberries so deftly that even the smartest purchaser thinks he is getting a bargain for twenty-five cents.

At larger towns a change for the better was noticeable in the clothing of the people. The most fashionable dress for the Mexican Indian was white muslin panteloons, twice as wide as those worn by the dudes last summer; a serape, as often cotton as wool, wrapped around the shoulders; a straw sombrero, and sometimes leather sandals bound to the feet with leather cords.

The women wear loose sleeveless waists with a straight piece of cloth pinned around them for skirts, and the habitual rebozo wrapped about the head and holding the equally habitual baby. No difference how cold or warm the day, nor how scant the lower garments, the serape and rebozo are never laid aside, and none seem too poor to own one. Apparently the natives do not believe much in standing, for the moment they stop walking they "hunker" down on the ground.

Never once during the three days did we think of getting tired, and it was with a little regret mingled with a desire to see more, that we knew when we awoke in the morning we would be in the City of Mexico.

[1] Pronounced Che-wa-wa.

CHAPTER IV.

THE CITY OF MEXICO.

"The City of Mexico," they had called. We got off, but we saw no city. We soon learned that the train did not go further, and that we would have to take a carriage to convey us the rest of the way.

Carriages lined the entrance to the station, and the cab men were, apparently from their actions, just like those of the States. When they procure a permit for a carriage in Mexico, it is graded and marked. A first-class carriage carries a white flag, a second-class a blue flag, and a third-class a red flag. The prices are respectively, per hour: one dollar, seventy-five cents, and fifty cents. This is meant for a protection to travelers, but the drivers are very cunning. Often at night they will remove the flag and charge double prices, but they can be punished for it.

We soon arrived at the Hotel Yturbide, and were assigned rooms by the affable clerk. The hotel was once the home of the Emperor Yturbide. It is a large building of the Mexican style. The entrance takes one into a large, open court or square. All the rooms are arranged around this court, opening out into a circle of balconies.

The lowest floor in Mexico is the cheapest. The higher up one goes the higher they find the price. The reason of this is that at the top one escapes any possible dampness, and can get the light and sun.

Our room had a red brick floor. It was large, but had no ventilation except the glass doors which opened onto the balcony. There was a little iron cot in each corner of the room, a table, washstand, and wardrobe.

It all looked so miserable—like a prisoner's cell—that I began to wish I was at home.

At dinner we had quite a time trying to understand the waiter and to make him understand us. The food we thought wretched, and, as our lunch basket was long since emptied, we felt a longing for some United States eatables.

I found we could not learn much about Mexican life by living at the hotels, so the first thing was to find some one who could speak English, and through them obtain boarding in a private family. It was rather difficult, but I succeeded, and I was glad to exchange quarters.

The City of Mexico makes many bright promises for the future. As a winter resort, as a summer resort, a city for men to accumulate fortunes; a paradise for students, for artists; a rich field for the hunter of the curious, the beautiful, and the rare. Its bright future cannot be far distant.

Already its wonders are related to the enterprizing people of other climes, who are making prospective tours through the land that held cities even at the time of the discovery of America.

Mexico looks the same all over; every white street terminates at the foot of a snow-capped mountain, look which way you will. The streets are named very strangely and prove quite a torment to strangers. Every block or square is named separately.

The most prominent street is the easiest to remember, and even it is peculiar. It is called the street of San Francisco, and the first block is designated as first San Francisco, the second as second San Francisco, and so on the entire street.

One continually sees poverty and wealth side by side in Mexico, and they don't turn up their noses at each other either; the half-clad Indian has as much room on the Fifth Avenue of Mexico as the millionaire's wife—not but what that land, as this, bows to wealth.

Policemen occupy the center of the street at every termination of a block, reminding one, as they look down the streets, of so many posts. They wear white caps with numbers on, blue suits, and nickel buttons. A mace now takes the place of the sword of former days. At night they don an overcoat and hood, which makes them look just like the pictures of veiled knights. Red lanterns are left in the street where the policemen stood during the daytime, while they retire to some doorway where, it is said, they sleep as soundly as their brethren in the States.

Every hour they blow a whistle like those used by street car drivers, which is answered by those on the next posts. Thus they know all is well. In small towns they call out the time of night, ending up with tiempo serono (all serene), from which the Mexican youth, with some mischievous Yankeeism, have named them Seronos.

CHAPTER V.

IN THE STREETS OF MEXICO.

In Mexico, as in all other countries, the average tourist rushes to the cathedrals and places of historic note, wholly unmindful of the most intensely interesting feature the country contains—the people.

Street scenes in the City of Mexico form a brilliant and entertaining panorama, for which no charge is made. Even photographers slight this wonderful picture. If you ask for Mexican scenes they show you cathedrals, saints, cities and mountains, but never the wonderful things that are right under their eyes daily. Likewise, journalists describe this cathedral, tell you the age of that one, paint you the beauties of another, but the people, the living, moving masses that go so far toward making the population of Mexico, are passed by with scarce a mention.

It is not a clean, inviting crowd, with blue eyes and sunny hair I would take you among, but a short, heavy-set people, with almost black skins, topped off with the blackest eyes and masses of raven hair. Their lives are as dark as their skins and hair, and are invaded by no hope that through effort their lives may amount to something.

Nine women out of ten in Mexico have babies. When at a very tender age, so young as five days, the babies are completely hidden in the folds of the rebozo and strung to the mother's back, in close proximity to the mammoth baskets of vegetables on her head and suspended on either side of the human freight. When the babies get older their heads and feet appear, and soon they give their place to another or share their quarters, as it is no unusual sight to see a woman carry three babies at one time in her rebozo. They are always good. Their little coal-black eyes gaze out on what is to be their world, in solemn wonder. No baby smiles or babyish tears are ever seen on their faces. At the earliest date they are old, and appear to view life just as it is to them in all its blackness.

They know no home, they have no school, and before they are able to talk they are taught to carry bundles on their heads or backs, or pack a younger member of the family while the mother carries merchandise, by which she gains a living. Their living is scarcely worth such a title. They merely exist. Thousands of them are born and raised on the streets. They have no home and were never in a bed. Going along the streets of the city late at night, you will find dark groups huddled in the shadows, which, on investigation, will turn out to be whole families gone to bed. They never lie down, but sit with their heads on their knees, and so pass the night.

When they get hungry they seek the warm side of the street and there, hunkering down, devour what they scraped up during the day, consisting of refused meats and offal boiled over a handful of charcoal. A fresh tortilla is the sweetest of sweetbreads. The men appear very kind and are frequently to be seen with the little ones tied up in their serape.

Groups of these at dinner would furnish rare studies for Rodgers. Several men and women will be walking along, when suddenly they will sit down in some sunny spot on the street. The women will bring fish or a lot of stuff out of a basket or poke, which is to constitute their coming meal. Meanwhile the men, who also sit flat on the street, will be looking on and accepting their portion like hungry, but well-bred, dogs.

This type of life, be it understood, is the lowest in Mexico, and connects in no way with the upper classes. The Mexicans are certainly misrepresented, most wrongfully so. They are not lazy, but just the opposite. From early dawn until late at night they can be seen filling their different occupations. The women sell papers and lottery tickets.

"See here, child," said a gray-haired lottery woman in Spanish. "Buy a ticket. A sure chance to get $10,000 for twenty-five cents." Being told that we had no faith in lotteries, she replied: "Buy one; the Blessed Virgin will bring you the money."

The laundry women, who, by the way, wash clothes whiter and iron them smoother even than the Chinese, carry the clothes home unwrapped. That is, they carry their hands high above their head, from which stream white skirts, laces, etc., furnishing a most novel and interesting sight.

"The saddest thing I ever saw," said Mr. Theo. Gestefeld, "among all the sad things in Mexico, was an incident that happened when I first arrived here. Noticing a policeman talking to a boy around whom a crowd of dusky citizens had gathered, I, true to journalistic instinct, went up to investigate. The boy, I found, belonged to one of the many families who do odd jobs in day time for a little food, and sleep at night in some dark corner. Strung to the boy's back was a dying baby. Its little eyes were half closed in death. The crowd watched, in breathless fascination, its last slow gasps. The boy had no home to go to, he knew not where to find his parents at that hour of the day, and there he stood, while the babe died in its cradle, his serape. In my newspaper career I have witnessed many sad scenes, but I never saw anything so heartrending as the death of that little innocent."

Tortillas is not only one of the great Mexican dishes but one of the women's chief industries. In almost any street there can be seen women on their knees mashing corn between smooth stones, making it into a batter, and finally shaping it into round, flat cakes. They spit on their hands to keep the dough from sticking, and bake in a pan of hot grease, kept boiling by a few lumps of charcoal. Rich and poor buy and eat them, apparently unmindful of the way they are made. But it is a bread that Americans must be educated to. Many surprise the Mexicans by refusing even a taste after they see the bakers.

There are some really beautiful girls among this low class of people. Hair three quarters the length of the women, and of wonderful thickness, is common. It is often worn loose, but more frequently in two long plaits. Wigmakers find no employment here. The men wear long, heavy bangs.

There is but one thing that poor and rich indulge in with equal delight and pleasure—that is cigarette smoking. Those tottering with age down to the creeping babe are continually smoking. No spot in Mexico is sacred from them; in churches, on the railway cars, on the streets, in the theaters—everywhere are to be seen men and women—of the elite—smoking.

The Mexicans make unsurpassed servants. Their thievery, which is a historic complaint, must be confined to those in the suburbs, for those in houses could not be more honest. There cleanliness is something overwhelming, when one recalls the tales that have been told of the filth of the "greasers." Early in the mornings the streets, walks in the plaza, and pavements are swept as clean as anything can be, and that with brooms not as good as those children play with in the States. Put an American domestic and a Mexican servant together, even with the difference in the working implements, and the American will "get left" every time. But this cleanliness may be confined somewhat to such work as sweeping and scrubbing; it does not certainly exist in the preparation of food. Pulque, which is sucked from the mother plant into a man's mouth and thence ejected into a water-jar, is brought to town in pig-skins. The skins are filled, and then tied onto burros, or sometimes—not frequently—carried in wagons, the filled skin rolling from side to side. Never less than four filled skins are ever loaded onto a burro; oftener eight and ten. The burros are never harnessed, but go along in trains which often number fifty. Mexican politeness extends even among the lowest classes. In all their dealings they are as polite as a dancing master. The moment one is addressed off comes his poor, old, ragged hat, and bare-headed he stands until you leave him. They are not only polite to other people, but among themselves. One poor, ragged woman was trying to sell a broken knife and rusty lock at a pawnbroker's stand. "Will you buy?" she asked, plaintively. "No, senora, gracias" (I thank you), was the polite reply.

The police are not to be excelled. When necessary to clear a hall of an immense crowd, not a rough word is spoken. It is not: "Get out of this, now;" "Get out of here," and rough and tumble, push and rush, as it is in the States among the civilized people. With raised cap and low voice the officer gently says in Spanish: "Gentlemen, it is not my will, but it is time to close the door. Ladies, allow me the honor to accompany you toward the door." In a very few moments the hall is empty, without noise, without trouble, just with a few polite words, among people who cannot read, who wear knives in their boots—if they have any—and carry immense revolvers strung to their belts; people who have been trained to enjoy the sight of blood, to be bloodthirsty. What a marked contrast to the educated, cultured inhabitants of the States.

Beneath all this ignorance there is a heart, as sympathetic, in its way, as that of any educated man. It is no unusual sight to see a man walk along with a coffin on his head, from which is visible the remains of some child. In an instant all the men in the gutters, on the walks, or in the doorways, have their hats off, and remain bare-headed until the sad procession is far away. The pall-bearer, if such he may be called, dodges in and out among the carriages, burros and wagons, which fill the street. The drivers lift their hats, but the silent bearer—generally the father—moves along unmindful of all. Funeral cars meet with the same respect.

In passing along where a new building was being erected, attention was attracted to the body of a laborer who had fallen from the building. A white cloth covered all of the body except his sandaled feet. "The Virgin rest his soul;" "Virgin Mother grant him grace," were the prayers of his kind as the policeman commanded his body to be carried away. These little scenes prove they are not brutes, that they are a little better than some intelligent people would have you believe.

The meat express does not, by any means, serve to make the meat, more palatable. Generally an old mule or horse that has reached its second childhood serves for the express. A long, iron rod, from which hooks project, is fastened on the back of the beast by means of straps. The meat is hung on these hooks, where it is exposed to the mud and dirt of the streets as well as the hair of the animal. Men with two large baskets, one in front, one behind, filled with the refuse of meat, follow near by. If they wear trousers they have them rolled up high so the blood from the dripping meat will not soil them, but run down their bare legs and be absorbed in the sand. It is asserted that the poor do not allow this mixture in the basket to go to waste, but are as glad to get it as we are to get sirloin steak.

Men with cages of fowls, baskets of eggs and bushels of roots and charcoal, come from the mountain in droves of from twenty-five to fifty, carrying packs which average three hundred pounds.

One form of politeness here is, that when complimenting or observing anything that belongs to a native, they will reply: "It is yours." That it means nothing but politeness some are slow to learn. "My house is yours; you have but to command me," said the hotel-keeper on the day of our arrival; but he made no move to vacate. A "greeny" from the States who was working for the Mexican Central tested some beer that was on its way to the city. "That is good beer," he remarked to the express man. "Si, senor! It is yours," was the reply. Mr. Green was elated, and trudged off home with the keg, much to the consternation and distress of the poor express man, who was compelled to pay out of his own purse for his politeness.

"You have very handsome coffins," was remarked to a man who, probably judging from our looks since we had struck Mexican diet, thought he had found a customer, and had insisted on showing every coffin in the house, even to the handles, plates, and linings. "Si, senorita, they are yours." Thinking they would be an unwelcome elephant on our hands we replied with thanks, and made our exit as quickly as possible. A young Spanish gentleman who, doubtless, was employed by the express company, said, after a few moments' conversation, "The express company and myself are yours, senorita." We confess to the stupidity of not accepting the bonanza, with him included.

A peep into doorways shows the people at all manner of occupations. Men always use the machines. Women and men put chairs together and weave bottoms in them. They also make shoes, the finest and most artistic shoe in the world, and the cobblers can make a good shoe out of one that is so badly worn as to be useless to our grandmothers as a rod of correction.

The water-carrier, aguador, is one of the most common objects on the street. They suspend water-jars from their heads, one in front, one back. Around their bodies are leather aprons to protect them from the water, which they get at big fountains and basins distributed throughout the city.

As a people they do not seem malicious, quarrelsome, unkind or evil-disposed. Drunkenness does not seem to be frequent, and the men, in their uncouth way, are more thoughtful of the women than many who belong to a higher class. The women, like other women, sometimes cry, doubtless for very good cause, and then the men stop to console them, patting them on the head, smoothing back their hair, gently wrapping them tighter in their rebozo. Late one night, when the weather was so cold, a young fellow sat on the curbstone and kept his arm around a pretty young girl. He had taken off his ragged serape and folded it around her shoulders, and as the tears ran down her face and she complained of the cold, he tried to comfort her, and that without a complaint of his own condition, being clad only in muslin trowsers and waist, which hung in shreds from his body.

Thus we leave the largest part of the population of Mexico. Their condition is most touching. Homeless, poor, uncared for, untaught, they live and they die. They are worse off by thousands of times than were the slaves of the United States. Their lives are hopeless, and they know it. That they are capable of learning is proven by their work, and by their intelligence in other matters. They have a desire to gain book knowledge, or at least so says a servant who was taken from the streets, who now spends every nickel and every leisure moment in trying to learn wisdom from books.

CHAPTER VI.

HOW SUNDAY IS CELEBRATED.

"A right good land to live in And a pleasant land to see."

Every day is Sunday, yet no day is Sunday, and Sunday is less Sunday than any other day in the week. Still, the Mexican way of spending Sunday is of interest to people of other climes and habits.

With the dawn of day people are to be seen wending their willing footsteps toward their church. The bells chime with their musical clang historic to Mexico, and men and women cross the threshold of churches older than the United States. Pews are unknown, and on the bare floor the millionaire is seen beside the poverty-stricken Indian; the superbly clad lady side by side with an uncombed, half naked Mexican woman. No distinction, no difference. There they kneel and offer their prayers of penitence and thanks, unmindful of rank or condition. No turning of heads to look at strange or gaze on new garments; no dividing the poor from the rich, but all with uniform thought and purpose go down on their knees to their God.

How a missionary, after one sight like this, can wish to convert them into a faith where dress and money bring attention and front pews, and where the dirty beggar is ousted by the janitor and indignantly scorned down by those in affluence, is incomprehensible.

No Mexican lady thinks it proper to wear a hat into church. She thinks it shows disgust; hence the fashion of wearing lace mantillas. In this city of rights there is nothing handsomer than a lady neatly clad in black with a mantilla gracefully wrapped around her head, under which are visible coal-black hair, sparkling eyes, and beautiful teeth.

A ragged skirt, and rebozo encircling a babe with its head on its mother's shoulder, fast asleep; black, silky hair which trails on the floor as she kneels, her wan, brown, pathetic face raised suppliantly in devotion, is one of the prettiest, though most common, sights in Mexico on Sunday morning.

This is the busiest day in the markets. Everything is booming, and the people, even on their way to and from church, walk in and out around the thousands of stalls, buying their marketing for dinner. Hucksters cry out their wares, and all goes as merry as a birthday party. Indians, from the mountains, are there in swarms with their marketing. The majority of stores are open, and the "second-hand" stalls on the cheap corner do the biggest business of the week.

Those who do not attend church find Mexico delightful on Sunday. In the alameda (park) three military bands, stationed in different quarters, play alternately all forenoon. The poor have a passion for music, and they crowd the park. After one band has finished, they rush to the stand of the next, where they stay until it has finished, and then move to the next. Thus all morning they go around in a circle. The music, of which the Mexican band was a sample, is superb; even the birds are charmed. Sitting on the mammoth trees, which grace the alameda, they add their little songs. All this, mingled with the many chimes which ring every fifteen minutes, make the scene one that is never forgotten. The rich people promenade around and enjoy themselves similar to the poor.

In the Zocalo, a plazo at the head of the main street and facing the palace and cathedral, the band plays in the evening; also on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

Maximilian planned and had made a drive which led to his castle at Chapultepec. It is 3750 feet long, wide enough to drive four, or even six teams abreast. It is planted on the east side with two rows of trees; one edging the drive, the other the walk, which is as wide as many streets. The trees are now of immense size, rendering this drive one of the handsomest, as well as most pleasant, in Mexico. Maximilian called it the Boulevarde Emperiale; but when liberty was proclaimed the name was changed to the Boulevarde of the Reform. On the same drive are handsome; nay more, magnificent statues of Columbus, Quatemoc, and an equestrian statue of Charles IV. of wonderful size, which has also been pronounced perfect by good judges. A statue of Cortez is being erected. This paseo is the fashionable promenade and drive from five to seven P.M. every day, and specially on Sunday afternoon. The music stands are occupied, and no vacant benches are to be found.

Those who call the Mexicans "greasers," and think them a dumb, ignorant class, should see the paseo on Sunday: tally-ho coaches, elegant dog-carts, English gigs, handsome coupes and carriages, drawn by the finest studs, are a common sight. Pittsburg, on this line, is nowhere in comparison. Cream horses, with silver manes and tails, like those so valued in other cities, are a common kind here. The most fashionable horse has mane and tail "bobbed." It might be added this style prevails to a great, very great extent among all animals. Cats and dogs appear minus ears and tails. Pets of every kind are much in demand. Ladies carry lap dogs, and gentlemen have chained to them blooded, dogs of mammoth size. The poor Mexican will have his tame birds; even roosters are stylish pets. "Mary had a little lamb" is respected too much here to be called "chestnut." The favorite pets of children are fleecy lambs, which, with bells and ribbons about their necks, accompany the children on their daily airing.

Mexico, while in the land of churches, would be rightly called the city of high heels, hats, powder and canes. Every gentleman wears a silk hat and swings a "nobby" cane. There are but two styles of hats—the tile hat and the sombrero. Every woman powders—lays it on in chunks—and wears the high heels known as the French opera heel. The style extends even to the men. One of the easiest ways to distinguish foreigners from natives is to look at their feet. The native has a neat shoe, with heels from two inches up, while the foreigner has a broad shoe and low heel. These people certainly possess the smallest hands and feet of any nation in the world. Ladies wear fancy shoes entirely—beaded, bronzed, colored leather, etc. A common, black leather shoe, such as worn by women in the States, is an unsalable article. Yet it is nothing strange to see a lady clad in silk or velvet, lift her dress to cross a street or enter a carriage, and display a satin shoe of exquisite make and above it the hosiery of Eve. In fact, very few women ever wear stockings at all.

This city is a second Paris in the matter of dress among the elite. The styles and materials are badly Parisian, and Americans who come here expecting to see poorly-dressed people are disappointed. Like people in the sister Republic, the Mexicans judge persons by their dress. It is the dress first and the man after.

On Sundays the streets and parks are thronged with men and women selling ice cream, pulque, candies, cakes, and other dainties. They carry their stock on their heads while moving, and when they stop they set it on a tripod, which they carry in their arms.

The flower sellers are always women, some of whom look quite picturesque in their gay-colored costumes. All the flowers are elegant, and are arranged in bouquets to suit either ladies or gentlemen.

Bull fights take no little part in the Sunday list of amusements, where the poor and rich mingle freely. Theaters have matinees and evening performances, and everything takes on a holiday look, and everybody appears happy and good-humored. This is nothing new in Mexico, however, for the most unusual sight is a fight or quarrel. These are left to the numerous dogs which belong to the city, and even they do little of it.

Riding horseback is a favorite pastime. Ladies only ride in the forenoon, as custom prevents them from indulging in the saddle after one o'clock. Gentlemen, however, ride mornings and evening. Among them are to be found the most graceful and daring riders in the world. Their outfits are gorgeous; true Mexican saddle trimmed with gold and silver, graceful flaps of the finest fur on bridles finished with numberless silver chains. The riders are superb in yellow goatskin suits, ornamented with silver horse shoes, whips, spurs, etc., with silver braid on the short coat. A handsome sombrero, finished in silver, with silver monogram of the owner, revolvers, and proud, fiery, high-stepping horse completed the picture. The ladies' habits are similar to those now in the States, except the fine sombrero which replaces the ugly, ungraceful high silk hats.

All day Sunday is like a pleasant Fourth of July, but after eight o'clock the carriages become scarcer and scarcer, the people go to the theaters and to their homes, the poor seek a soft flagstone, where they repose for the night, and by nine o'clock the streets make one think of a deserted city.

Mexicans do not go half way in the matter of style. At one o'clock Sunday afternoons policemen in fancy uniforms, mounted on handsome horses, equipped with guns and lassoes, ride down the Boulevard. They are stationed in the center of the drive one hundred yards apart, every alternate horse's head in the same direction. There they remain, like statues, the entire afternoon. Sunday is a favorite day for funerals and change of residence. Men with wardrobes, pianos, etc., on their backs are seen trotting up and down the streets like our moving wagons on the first day of April. They mean well by work on Sunday, but it would appear awful to some of our good people at home. There is this advantage, at least: they have something better to do than to congregate in back-door saloons or loaf on the streets.

CHAPTER VII.

A HORSEBACK RIDE OVER HISTORIC GROUNDS.

A Sunday in Mexico is one long feast of champagne, without a headache the next day. When the first streaks of dawn appear in the east people bob out from this street and that, hostlers hurry horses off to private residences, gay riders whirl by as if eager to catch the shades of night as they are sinking in the west, and by 6:30 it looks as if all Mexico was on horseback. Ladies wear beautiful costumes, dark habits, short skirts, silver and gold buttons, and broad sombreros. Men display greater variety of costumes: some wear yellow buckskin suits trimmed with gold or silver, others have a drab skin suit artistically trimmed, still others wear light cloth suits and high boots, buttoned at the side, and reaching the knee. A belt holding a revolver, and a Mexican saddle to which is fastened a sword complete this beautiful riding suit. And then what riders! It is the poetry of motion; they are as but part of the perfect horse they ride. Take the beautiful horses, artistic outfit, grand eyes glancing at you from beneath a pretty sombrero, and you have a Mexican scene which is irresistible. Even Americans are a thousand times handsomer when they don this outfit, and it is safe to wager that if the men in the States would adopt the Mexican riding-suit, there would not be a single man left after a two months' trial.

After searching the whole city over we at last found a woman we knew, who owned a habit. "Certainly you may have it, with great pleasure," and we thought what an angel she was until the time we needed it, when she sent a reply: "My riding-dress is, as I told you, at your service any day in the week but Sunday. I am surprised that you find need of it on that blessed day." That evening on going to a house for dinner we found her there, dressed to the height of fashion, discussing the people who had attended church in the morning and telling what a lovely drive she had on the paseo in the afternoon. She is a missionary.

However, as the sun was creeping up trying to catch night unawares, I mounted a horse, clad in a unique and original costume, to say the very least, which the gallant young men, however, pronounced odd and pretty, and wanted to know if it was the style of the States. The boulevard of the Reform looked as cool and sweet as a May morning in the country, and finer than a circus parade with the hundreds of horsemen going either way. "Vamos?" (Let us go). "Con mucho gusto" (with much pleasure), was our reply, and away flew our willing steeds, bearing us soon to the paradise of Mexico—Chapultepec.

Greeting the guards at the gate, we entered, riding under trees which sheltered Montezuma and his people, Cortes and his soldiers, poor Maximilian and Charlotta, where Mexican cadets laid down their lives in defense of their country, where the last battle was fought with the Americans, and where now is being prepared the future home of President Diaz. Around the castle and through the grounds we at last emerged at the opposite side. Here a scene worthy of an artist's brush was found. In a small adobe house, faced in front by a porch, were half-clad Mexicans dealing out coffee and pulque to the horsemen who surrounded the place. One had even ridden into the house. Awaiting our turn we viewed the scene. On our left were mounted and unmounted uniformed soldiers guarding one of the gates to Chapultepec. At our back were trains of loaded burros, about 200, on their way to market in the city. They stood around and about the old aqueduct, the picture of patience. Some few had lain down with their burdens and had to be assisted to their feet by their masters. Numerous little charcoal fires, above which were suspended pans and kettles, were being fanned by enterprising peons, who had started this restaurant to make a few pennies from their fellowmen. One fellow cut all kinds of meat, on a flat stone, into little pieces, which he deposited together in a kettle of boiling water, and picking them out again with a long stick sold them, half-cooked, to the waiting people. Some women were busily knitting, weaving baskets, etc., as they waited for this dainty repast. At last our turn came, and we turned our back on the outdoor restaurants while we endeavored to swallow a little bit of the miserable stuff they called coffee. As we started we saw the people adjust the burdens to their backs, take up their long walking-poles, and start their burros toward the city. They had feasted and were now ready to continue their journey.

Leaping a ditch we left the highway and traveled through the fields, stopping to gather a few pepper berries with which to decorate ourselves, admiring the many-colored birds flitting from tree to tree. Another ditch, which the horses cleared beautifully, was left behind, and we were once again on a highway, with dust about a foot deep, which made horses cough as well as their riders. "This is bad," one of the gentlemen managed to say at last. We were only able to give a sympathetic grunt and then had to gasp fifteen minutes before we could regain our breath. "There is a hacienda near where we will get a drink and change roads. Vamos." Off we went, leaving the dust behind, and were soon in the shaded drive leading to the hacienda.

Here, at Huischal, we soon forgot the scorching sun and blinding dust and gave ourselves up to the pleasure of the moment, watching the ever picturesque people gathered in groups beneath the shade. Under the trees were droves of horses, which were taken two by two, and led into a large walled pond. A peon walked on the wall, holding the bridle of the tethered horses, who swam from one end to the other, covered all but the head. After the bath the horses were rubbed well until they glistened like satin.

Climbing the hill we passed all kinds of Indians and huts. There were homes built entirely of the maguey plant, where straw mats served for beds. The people were all awake and engaged in various occupations; some women were washing, some were making their toilet—combing their hair with the same kind of brush they scrub with, and washing their bodies with a porous soapstone common to the country. Very few of the children had any clothing at all, but happiness reigned supreme. We passed several plain wooden crosses with inscriptions on them, asking travelers to pray for the deceased's soul. It brought forcibly to mind Byron's "Childe Harold."

Quite on the top of the hill, and facing Chapultepec, gleams a marble monument erected in honor of the Mexicans killed while defending Casa de Mata (the house of the dead) and El Molino del Rey (the mill of the king). The Americans discovered, while encamped near here, that cannon, etc., were being manufactured at El Molino, so they decided to storm the place; they found the work more difficult than they expected. The Mexicans were fighting for a country they loved, and for which they had been compelled to fight for generations. Their walls were strong, but at last they gave way before the heavy artillery of the Americans, and their dead covered the battlefield. Casa de Mata is now a garrison, and the soldiers march back and forth with sad faces. El Molino del Rey now furnishes flour for the city. It shows no trace of the assault. Near by is a foundry for the manufacture of guns and munitions.

The city of the dead, Dolores, lies to the back of the mill. Funeral cars and draped street cars were just returning from the cemetery, and as the people are not allowed to ride or drive along this carway, we crossed into a plantation of pulque plant. It is a resentful thing, and a whole army in itself. It ran its sharp prongs into the legs of the men, endeavored to pull the skirts off the women, and played spurs on the horses; but we finally emerged at the entrance of the cemetery, alive, but wiser from our experience.

Mexican cemeteries have a certain peculiar beauty, and yet they are ugly. No one is allowed to ride or drive through; coffins are carried in and everybody is compelled to walk. Beautiful trees are cultivated, even the apple and the peach being reared for ornament. The walks are laid out nicely. Spruce trees are trained to form an arbor for long distances. Where they are divided or meet another walk, flowing fountains with large basins and statues grace the spot. One statue, which looked rather singular, was apparently carved out of wood. It represented a man with flowing locks and beard, clad in a long gown and holding in one hand a round ball. Time had its hand on heavily, and the wood was seamed and browned. Altogether it was a disreputable-looking thing. The keeper said it represented Christ with the world in his hand. Not a sprig of grass is permitted to grow in any of the graveyards, and they are swept as clean as our grandmother's backyard used to be.

Men were busy digging graves, and new ones were completely hidden by fresh flowers, and the flowers on others were withered and dead, as if the one so lately buried was already forgotten. The monuments are quite fine. Some have little altars on which candles are lighted on certain days. The prevailing style of marble shaft is coffin shaped. Some graves have miniature summer-houses built over them, the framework covered with Spanish moss. The effect is beautiful. The poor have only black and white wooden crosses to mark their ashes. One family had built a cave, formed of volcanic stone, over the grave, the effect being quite pretty and unique.

After partaking of refreshments at a long, low building, just outside the cemetery gate, we rode across the country and into Tacubaya, an ancient city once the home of Montezuma's favorite chief, where the American soldiers were encamped, now the home of Mexican millionaires, the site of the feast of the gamblers, and the prettiest village in Mexico. The gambling feast has ended and the town has been restored to its usual quietness. In the center plaza a band was holding forth, as is the custom in every Mexican village on Sunday mornings. People had gathered in sun and shade listening. The markets were in full blast; the thousands of luscious fruits looking fresh and inviting as they were spread on the ground awaiting buyers. The native ware was so peculiar and the "merchant"—half-dressed, brown and pleasant—was more than we could resist, so buying two small cream jugs, made after the style in vogue fifty years ago, we paid him two reals (fifty cents) and departed, leaving him happy.

Once again the willing horses climbed the hill, and reaching the summit we inspected the waterworks which have so faithfully supplied the city for years. A weather-beaten frame house hid the well or spring that has given such a generous supply. A wooden wheel as large as the house itself, moved slowly, as if age and rheumatism had stiffened its joints. The water flowed gently through an open trench into another building, whence it rushed, white, foaming and sparkling, into the ground, leaving only high brick air-pipes to mark its course to the aqueduct.

By the side of the trench a woman was doing her washing, and two little lads, with poles across their shoulders and buckets suspended from either end, were carrying water to the houses down in the valley. An old cow with curly horns gazed at us in astonishment as we invaded her private meadow to get a view of a paper mill, which is built in the shape of an old English castle, down in a deep ravine in a nest of lovely green trees. The old cow had evidently come to the conclusion, after deliberate reasoning, that we were intruding, and she charged our horses in a first-class "toro" style. There were no capeadores to attract her attention, no bourladeras for us to hide behind, so we thought it best to fly, which we did with a Maud S speed. I did not mention I had lost my hat in the retreat until we were over the trench, and one of the young men gallantly started to recover it, against the protestations of the entire crowd. We expected to see him killed, but the cow stood watching him as he dismounted for the feminine headgear, gesticulating with head and tail and beating the earth with her fore legs. Remounting, he saluted her, then putting spurs to his horse he cleared the ditch, leaving the baffled and angry cow on the other side.

La Castaneda, the great pleasure-garden of the Mexicans, was next visited. Beautiful flowers, shrubbery and marble statues grace the well-kept resort. Neat little benches, cunning little vine-draped nooks, sprinkling-fountains, secluded dancing-stands, deep bathing-basins, are a few of the many attractions. Shaded walks and twisting stairways would always bring us to some new beauty. Music and dancing are always held here every afternoon, and although it was nearly noon they had not even so much as a cracker in the house. In Mexico nothing in the line of edibles is kept in the house overnight.

At Mixcoac we visited the famous flower gardens, and viewed the site where the American soldiers were garrisoned during the war. The Mexicans have found a new thing—a pun, and they are enjoying it heartily. It is not very brilliant or very funny, but it is traveling over the city, and every person has to repeat it to you. An American wanted to see Mixcoac—pronounced "Mis-quack." The conductor failed to let him out at the place, and turning to the Mexicans he said: "We have mis-t-quack." But it was funnier still to an American who was being showed around by a Mexican who spoke very little English. "I will take you to see Mis-quack," said the Mexican. The American expressed his pleasure and willingness. "This is all Mis-quack," said the Mexican, pointing around the entire town. "Indeed," ejaculated the astonished tourist; "Miss Quack must be very wealthy."

Down the dusty road we came, passing natives shooting the pretty birds just for the fun of the thing. All other riders had disappeared, and people looked at us from beneath the shade in amazement, and even we felt a little tired and heated after a thirty-mile ride. We reached home at one o'clock. Since then I have been wearing blisters on my cheeks and nose, and making frequent applications with the powder rag of the literary widow and old-maid artist who room across the way.

CHAPTER VIII.

A MEXICAN BULL-FIGHT.

Mexicans are always mauana until it comes to bull-fights and love affairs. To know a Mexican in daily life is to witness his courtesy, his politeness, gentleness; and then see him at a bull-fight, and he is hardly recognizable. He is literally transformed. His gentleness and "mauana" have disappeared; his eyes flash, his cheeks flush—in fact, he is the picture of "diabolic animation." It is all "hoy" to-day with him. Even the Spanish lady of ease and high heels forgets her mannerisms and appears like some painted heathen jubilant over the roasting of a zealous missionary.

There have been some very good bull-fights lately in the suburbs, for fighting is prohibited within a certain distance of the city. When they say a good bull-fight, it means that the bulls have been ferocious and many horses and men have been killed.

It is safe to say that the majority of Americans who visit Mexico do like the natives, even on the first Sunday; attend divine service in the morning, a bull-fight in the afternoon and theater in the evening. But it is with regret that I say that many Americans who are residents of the city now are as passionately fond of the national inhuman sport as a native who has been reared up to it. Some never miss a fight, and their American voice outstrips the Mexican in the shouts of "bravo" at the bloody thrusts. Yet there are tourists who cannot outsit one performance, and have no desire to attend a second. While we Americans cry "brutal" against the national amusement, they in return cry "brutal" to our prize-fights, in which they see nothing to admire, and a dog-fight is beneath their contempt.

"Your humane societies would prevent bull-fights in the States," said a Spanish gentleman; "your people would cry out against them. Yet they have strong men trying to pound one another to death, and the people clamor for admission to see the law kill men and women, while in health and youth, because of some deed done in the flesh. Yes, they witness and allow such inhuman treatment to a fellow mortal and turn around and affect holy horror at us for taking out of the world a few old horses and furnishing beef for the poor."

Read of glorious bull-fights and then witness one, and the scene is entirely changed. The day of their glory has departed. When Maximilian graced the country with his presence the fights were indeed fitted for royal sight. The costumes were of the costliest material; the horses were of the best blood and breed, and the bulls regular roaring Texans, which needed no second sight of a red capa to raise their feverish ire. No fight cost less than $5,000.

Now all is different. Maximilian lies in a grave to which a treacherous bullet consigned him; Carlotta, still what that bullet made her, a raving lunatic and a widow. Men of low degree are permitted to grace the fights, which are but miserable shadows, a farce of the former royal days.

The National—a narrow gauge—and the Mexican Central, run special trains consisting of twenty and twenty-five cars, first, second, and third-class, to the fights every half hour. Tickets are sold during the week, which include railroad fare, admission to grounds and seat. Long before the time for leaving, carriages pull up to the stations and blooming senoras, fair senoritas, handsome senors and delicate, lovely children, dressed in the height of wealth and fashion, enter the railway coach and proceed to make themselves comfortable for the half hour or hour's ride which is to bring them to their destination. Bands march up and are disposed of in the coaches, and last comes a troop of soldiers, clad in buckskin suits, elaborately trimmed with silver ornaments, yard wide sombreros, and armed with gun, revolver, sword, dagger, mace, and lasso, which they have no hesitation in using in quite a characteristic manner, asking no questions, expecting no information, performing their duties fatally.

They are the "daisies" of Mexico, and in appreciation of which they are sent to grace every bull fight! They are the best paid soldiers in the Republic, receiving $1 a day, while the highest salary paid to any of the others is twenty-five cents daily, out of which they provide their own wearing apparel and food. The same "daisies" were all outlaws, bandits, fierce and uncontrollable. Their many deeds, always done in the name of the law, are fearful to relate, so the present president thought it policy to engage their services. They ride handsome horses, furnished by the government, and are said to be the most faithful, reliable men in the employ of the Republic. Their only fault is killing without asking questions, for which they go scot-free without even so much as a rebuke. The "daisies" have some of the finest specimens of manhood in Mexico, and number in their list some handsome, open-faced, youthful boys. They can maintain order among 6,000 people filled with pulque without uttering one word. Their presence is sufficient.

On speeds the train. Above the din arises the musical sound of a strange language. A view from the window exhibits some of Mexico's most beautiful scenery. Now we pass beautiful farms, magnificent artificial lakes covered with wild duck, which would delight the heart of our American hunters, as they arise in dark clouds on the approach of the train, and move off to a more secluded spot; beautiful fields of grain, and acres and acres of pulque plant, quaint huts, picturesque, historic churches, ancient monastries and convents, now used for other purposes, all surrounded by snow-capped mountains. For miles we keep our eyes on the strangest and grandest mountain in Mexico, the White Lady, or the Sleeping Virgin. It deserves chapters of description and praise, but feeling our inability to do it justice we shall confine ourselves to a brief remark.

Outlined against a blue sky, only such skies as are habitual to Italy and Mexico, is a snow-topped mountain in form of a woman lying on a straight cot; on the head is a snow band, such as worn by Sisters of Mercy. The arms are folded peacefully on the breast, and the snow garments fall in graceful folds over the feet. There she lies and has lain for centuries in perfect outline and peaceful repose. Even as we look the clouds play fantastically about the beauteous form. Now they cover her body like a dark shroud. Again they drape her cot like a pall, then rise in a threatening attitude above her fair head, but undisturbed she lies there with hands ever folded above the quiet heart, proudly indifferent to storm or shine, clad in her pure snowy garments, truly the most beauteous sight in Mexico. With a sigh we at last leave her behind and are rudely brought to earth by the announcement that we have reached our destination.

The bull ring resembles somewhat a racecourse; the highest row is covered and called boxes. They are divided into small squares, which are meant to hold six but are crowded with four. Miserable chairs without backs are the comfortable seats. Below is the amphitheater, arranged exactly like circus seats. Different prices are charged and the cheapest is the sunny side, where all the poor sit. A fence painted in the national colors—red, green and white—of some six feet in height, incloses the ring. Three band-stands, equal distances apart, are filled with brilliantly uniformed musicians.

The judge is appointed by the municipality, but the fighters have a right to refuse to fight under one judge whom they think will compel them to take unnecessary risks with a treacherous bull, for a judge once chosen his commands are law, and no excuse will be accepted for not obeying, but a fine deducted from the fighter's salary, and he loses cast with the audience. The judge is in a box in the center of the shady side; with him is some prominent man, for every fight must be honored with the presence of some "high-toned" individual, while behind stands the bugler, a small boy in gay uniform, with a bugle slung to his side, by which he conveys the judge's whispered commands to the fighters in the ring.

Below the judge hangs a row of banderillas. They are wooden sticks about two feet long with a barbed spear of steel in the end, which are stuck in the bull to gore him to madness. They are always gayly decorated with tinsel and gaudy streamers of the national colors. Sometimes firecrackers are ingeniously inserted, which go off when the banderilla is deftly fastened in the beast's quivering flesh.

The bands play alternately lively airs, the audience for once find no charms in the music and forget to murmur mauana, but soon begin to cry "El toro! El toro!" (The bull! the bull!)

The judge nods to the bugler, and as he trumpets forth the gate is swung open and the grand entry is made. First comes "El Capitan" or matador, chief of the ring, and the men who kill the bull with a sword. Next eight capeadores, whose duty consists in maddening the bull and urging it to fight by flinging gay-colored capas or capes in its face. Two picadores, who are armed with long poles, called picas, in the end of which are sharp steel spears which they fight the bull with. After come the lazadores, dressed in buckskin suits, elaborately trimmed with silver ornaments and broad, expensive sombreros. They ride fine horses, and do some very pretty work at lassoing. Three mules abreast, with gay plumes in their heads, and a man with a monstrous wheelbarrow of ancient make, close up the rear. All range before the judge and make a profound bow, after which the mules and wheelbarrow disappear.

The dresses of the fighters are very gorgeous: satin knee-breeches and sack coat of beautiful colors, and highly ornamented, beaded, etc. On the arm is carried the capa, a satin cape, the color of the suits, and little rough caps, tied under the chin, grace the head. At the back of the head is fastened false hair, like a Chinaman's, familiarly known as "pig tail." Two gayly painted clowns, who, unlike those in the States, never have anything to say, are always necessary to complete the company in the ring.

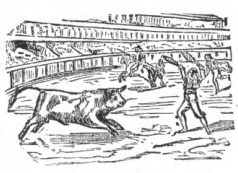

Again the bugle sounds, the band strikes out in all its might, the people rise to their feet and cry "El toro," the fighters form a semicircle around a door, el capitan draws a bolt, flings it open, and as the bull springs forth from his dark and narrow cell a man perched above sticks two banderillas into his neck to madden him. With a snort of rage he rushes for the capas. As they are flirted before his eyes, he tramples them under his hoofs, and the capeadores escape behind the bourladera, a partition six feet wide, placed in the arena at four places equally distant.

At the trumpet sound a banderilla runs out waving the banderillas above his head. He faces the maddened bull with a calm smile. The bull paws the ground, lowers his head, and with a bellow of rage makes for his victim. Your eyes are glued to the spot.

It is so silent you can hear your heart throb. There can be no possible escape for the man. But just as you think the bull will lift him on his horns you see the two banderillas stuck one in either side of the neck, and the man springs safely over the lowered head and murderous horns of the infuriated animal, as it rushes forward to find the victim has escaped. The audience shout "bravo," and wave their serapes, sombreros and clap their hands. The bull roars with pain, and the banderillas toss about in the lacerated flesh, from which the blood pours in crimson streams. "Poor beast! what a shame," we think, and even then the order is given for the picador to attack the bull.

The horse on which the picador is mounted is bought only to be killed. It is an old beast whose days of beauty and usefulness are over; $2 or $4 buys him for the purpose. Sometimes he is hardly able to walk into the ring. First the brute is blindfolded with a leather band, and a leather apron is fastened around his neck in pretense of saving him from being gored.

The picador guides the blinded horse to face the bull. Capas are flung before the bull tauntingly. The picador dives the pica into the beast and it vents its pain on the horse. Blood pours from the wound; trembling the horse stands, unable to see what has wounded it. Again, they coax the bull to charge, and place the horse so that the murderous horns will disembowel it. Down goes the blinded beast, and the capeadores flaunt their capas at the bull while the picadore gets off the dying animal, which is lassoed and dragged from the ring. Another horse is brought in, and the same work is gone over until the horse is killed.