Recollections of Abraham Lincoln, 1847-1865 by Ward Hill Lamon

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

RECOLLECTIONS

of

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

1847-1865

By

WARD HILL LAMON

EDITED BY DOROTHY LAMON TEILLARD

WASHINGTON, D. C.

PUBLISHED BY THE EDITOR

1911

Copyright

By Dorothy Lamon

A.D. 1895

Copyright, 1911

By Dorothy Lamon Teillard

All rights reserved

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

PREFACE.

The reason for thinking that the public may be interested in my father's recollections of Mr. Lincoln, will be found in the following letter from Hon. J. P. Usher, Secretary of the Interior during the war:—

Lawrence, Kansas, May 20, 1885.

Ward H. Lamon, Esq., Denver, Col.

Dear Sir, — There are now but few left who were intimately acquainted with Mr. Lincoln. I do not call to mind any one who was so much with him as yourself. You were his partner for years in the practice of law, his confidential friend during the time he was President. I venture to say there is now none living other than yourself in whom he so much confided, and to whom he gave free expression of his feeling towards others, his trials and troubles in conducting his great office. You were with him, I know, more than any other one. I think, in view of all the circumstances and of the growing interest which the rising generation takes in all that he did and said, you ought to take the time, if you can, to commit to writing your recollections of him, his sayings and doings, which were not necessarily committed to writing[vi] and made public. Won't you do it? Can you not, through a series of articles to be published in some of the magazines, lay before the public a history of his inner life, so that the multitude may read and know much more of that wonderful man? Although I knew him quite well for many years, yet I am deeply interested in all that he said and did, and I am persuaded that the multitude of the people feel a like interest.

Truly and sincerely yours,

(Signed) J. P. Usher.

In compiling this little volume, I have taken as a foundation some anecdotal reminiscences already published in newspapers by my father, and have added to them from letters and manuscript left by him.

If the production seems fragmentary and lacking in purpose, the fault is due to the variety of sources from which I have selected the material. Some of it has been taken from serious manuscript which my father intended for a work of history, some from articles written in a lighter vein; much has been gleaned from copies of letters which he wrote to friends, but most has been gathered from notes jotted down on a multitude of scraps scattered through a mass of miscellaneous material.

D. L.

Washington, D. C.,

March, 1895.

PREFACE

TO THE SECOND EDITION.

In deciding to bring out this book I have had in mind the many letters to my father from men of war times urging him to put in writing his recollections of Lincoln. Among them is one from Mr. Lincoln's friend, confidant, and adviser, A. K. McClure, one of the most eminent of American journalists, founder and late editor of "The Philadelphia Times," of whom Mr. Lincoln said in 1864 that he had more brain power than any man he had ever known. Quoted by Leonard Swett, in the "North American Review," the letter is as follows:—

Philadelphia, Sept. 1, 1891.

Hon. Ward H. Lamon, Carlsbad, Bohemia:

My dear old Friend, — ....I think it a great misfortune that you did not write the history of Lincoln's administration. It is much more needed from your pen than the volume you published some years ago, giving the history of his life. That straw has been thrashed over[viii] and over again and you were not needed in that work; but there are so few who had any knowledge of the inner workings of Mr. Lincoln's administration that I think you owe it to the proof of history to finish the work you began. —— and —— never knew anything about Mr. Lincoln. They knew the President in his routine duties and in his official ways, but the man Lincoln and his plans and methods were all Greek to them. They have made a history that is quite correct so far as data is concerned, but beyond that it is full of gross imperfections, especially when they attempt to speak of Mr. Lincoln's individual qualities and movements. Won't you consider the matter of writing another volume on Lincoln? I sincerely hope that you will do so. Herndon covered about everything that is needed outside of confidential official circles in Washington. That he could not write as he knew nothing about it, and there is no one living who can perform that task but yourself....

Yours truly,

(Signed) A. K. McClure.

I have been influenced also by a friend who is a great Lincoln scholar and who, impressed with the injustice done my father, has urged me for several years to reissue the book of "Recollections," add a sketch of his life and publish letters that show his standing during Lincoln's administration. I hesitated to do this, remembering the following words of Mr. Lincoln at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on his way to Washington: "It is well known that the more a man speaks the less he is[ix] understood—the more he says one thing, the more his adversaries contend he meant something else." I am now yielding to these influences with the hope that however much the book may suggest a "patchwork quilt" and be permeated with Lamon as well as Lincoln, it will yet appeal to those readers who care for documentary evidence in matters historical.

Dorothy Lamon Teillard.

Washington, D. C.,

April, 1911.

CONTENTS.

| Letter from Ex-Secretary Usher. | |

| Letter from A. K. McClure. | |

| Memoir of Ward H. Lamon. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Page | |

| EARLY ACQUAINTANCE. | |

| Prominent Features of Mr. Lincoln's Life written by himself | 9 |

| Purpose of Present Volume | 13 |

| Riding the Circuit | 14 |

| Introduction to Mr. Lincoln | 14 |

| Difference in Work in Illinois and in Virginia | 15 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Victory over Rev. Peter Cartwright | 15 |

| Lincoln Subject Enough for the People | 16 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Love of a Joke—Could "Contribute Nothing to the End in View" | 16 |

| A Branch of Law Practice which Mr. Lincoln could not learn | 17 |

| Refusal to take Amount of Fee given in Scott Case | 18 |

| Mr. Lincoln tried before a Mock Tribunal | 19 |

| Low Charges for Professional Service | 20 |

| Amount of Property owned by Mr. Lincoln when he took the Oath as President of the United States | 20 |

| Introduction to Mrs. Lincoln | 21 |

| Mrs. Lincoln's Prediction in 1847 that her Husband would be President | 21 |

| The Lincoln and Douglas Senatorial Campaign in 1858 | 22 |

| "Smelt no Royalty in our Carriage" | 22 |

| Mr. Lincoln denies that he voted against the Appropriation for Supplies to Soldiers during Mexican War | 23 |

| Jostles the Muscular Democracy of a Friend | 24 |

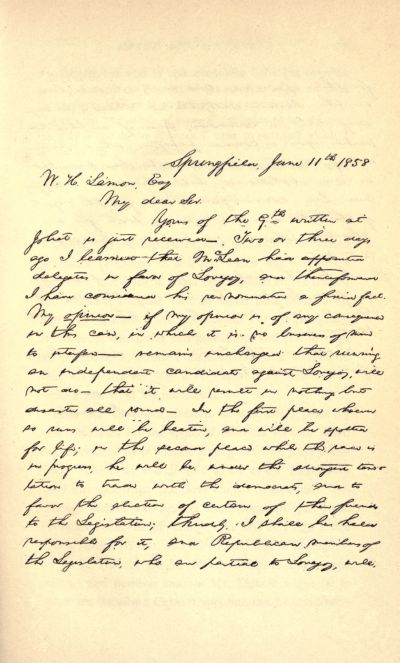

| Political Letter of 1858 | 26 |

| Prediction of Hon. J. G. Blaine regarding Lincoln and Douglas | 27 |

| Time between Election and Departure for Washington | 28 |

| [xii] | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| JOURNEY FROM SPRINGFIELD TO WASHINGTON. | |

| Mr. Lincoln's Farewell to his Friends in Springfield | 30 |

| At Indianapolis | 32 |

| Speeches made with the Object of saying Nothing | 33 |

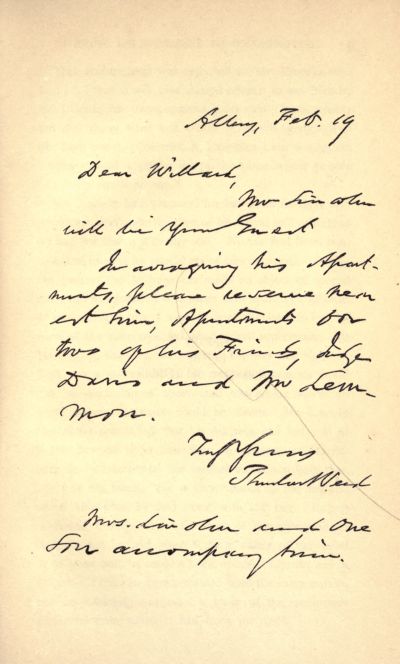

| At Albany—Letter of Mr. Thurlow Weed | 34 |

| Loss of Inaugural Address | 35 |

| At Philadelphia—Detective and alleged Conspiracy to murder Mr. Lincoln | 38 |

| Plans for Safety | 40 |

| At Harrisburg | 40 |

| Col. Sumner's Opinion of the Plan to thwart Conspiracy | 41 |

| Selection of One Person to accompany Mr. Lincoln | 42 |

| At West Philadelphia—Careful Arrangements to avoid Discovery | 43 |

| At Baltimore—"It's Four O'clock" | 45 |

| At Washington | 45 |

| Arrival at Hotel | 46 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| INAUGURATION. | |

| Formation of Cabinet and Administration Policy | 48 |

| Opposition to Mr. Chase | 49 |

| Alternative List of Cabinet Members | 50 |

| Politicians realize for the First Time the Indomitable Will of Mr. Lincoln | 51 |

| Mr. Seward and Mr. Chase, Men of Opposite Principles | 51 |

| Mr. Seward not to be the real Head of the Administration | 52 |

| Preparations for Inauguration | 53 |

| Introduction by Senator Baker | 53 |

| Impression made by Inaugural Address | 54 |

| Oath of Office Administered | 54 |

| The Call of the New York Delegation on the President | 55 |

| [xiii] | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| GLOOMY FOREBODINGS OF COMING CONFLICT. | |

| Geographical Lines distinctly drawn | 56 |

| Behavior of the 36th Congress | 57 |

| Letter of Hon. Joseph Holt on the "Impending Tragedy" | 58 |

| South Carolina formally adopts the Ordinance of Secession | 62 |

| Southern Men's Opinion of Slavery | 62 |

| Mr. Lincoln imagines Himself in the Place of the Slave-Holder | 65 |

| Judge J. S. Black on Slavery as regarded by the Southern Man | 66 |

| Emancipation a Question of Figures as well as Feeling | 66 |

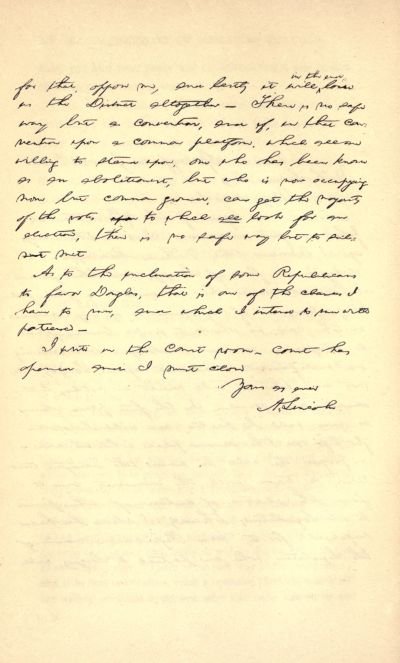

| Mission to Charleston | 68 |

| "Bring back a Palmetto, if you can't bring Good News" | 70 |

| Why General Stephen A. Hurlbut went to Charleston | 70 |

| Visit to Mr. James L. Pettigrew—Peaceable Secession or War Inevitable | 71 |

| "A great Goliath from the North"—"A Yankee Lincoln-Hireling" | 72 |

| Initiated into the great "Unpleasantness" | 73 |

| Interview with Governor Pickens—No Way out of Existing Difficulties but to fight out | 74 |

| Passes written by Governor Pickens | 75,78 |

| Interview with Major Anderson | 75 |

| Rope strong enough to hang a Lincoln-Hireling | 76 |

| Timely Presence of Hon. Lawrence Keith | 77 |

| Extremes of Southern Character exemplified | 77 |

| Interview with the Postmaster of Charleston | 78 |

| Experience of General Hurlbut in Charleston | 79 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| HIS SIMPLICITY. | |

| The Ease with which Mr. Lincoln could be reached | 80 |

| Visit of a Committee from Missouri | 81 |

| A Missouri "Orphan" in Trouble | 82 |

| Protection Paper for Betsy Ann Dougherty | 83 |

| Case of Young Man convicted of Sleeping at his Post | 86 |

| [xiv] | |

| Reprieve given to a Man whom a "little Hanging would not hurt" | 87 |

| An Appeal for Mercy that failed | 88 |

| An Appeal for the Release of a Church in Alexandria | 89 |

| "Reason" why Sentence of Death should not be passed upon a Parricide | 90 |

| The Tennessee Rebel Prisoner who was Religious | 90 |

| The Lord on our Side or We on the Side of the Lord | 91 |

| Clergymen at the White House | 91 |

| Number of Rebels in the Field | 92 |

| Mr. Lincoln dismisses Committee of Fault-Finding Clergymen | 93 |

| Mistaken Identity and the Sequel | 94 |

| Desire to be like as well as of and for the People | 96 |

| Hat Reform | 97 |

| Mr. Lincoln and his Gloves | 97 |

| Bearing a Title should not injure the Austrian Count | 99 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| HIS TENDERNESS. | |

| Mr. Lincoln's Tenderness toward Animals | 101 |

| Mr. Lincoln refuses to sign Death Warrants for Deserters—Kind Words better than Cold Lead | 102 |

| How Mr. Lincoln shared the Sufferings of the Wounded Soldiers | 103 |

| Letters of Condolence | 106-108 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| DREAMS AND PRESENTIMENTS. | |

| Superstition—A Rent in the Veil which hides from Mortal View what the Future holds | 111 |

| The Day of Mr. Lincoln's Renomination at Baltimore | 112 |

| Double Image in Looking-Glass—Premonition of Impending Doom | 112 |

| Mr. Lincoln relates a Dream which he had a Few Days before his Assassination | 114 |

| [xv] | |

| A Dream that always portended an Event of National Importance | 118 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Last Drive | 119 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Philosophy concerning Presentiments and Dreams | 121 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE HUMOROUS SIDE OF HIS CHARACTER. | |

| Mr. Lincoln calls himself "Only a Retail Story-Dealer" | 123 |

| The Purpose of Mr. Lincoln's Stories | 124 |

| Mr. Lincoln shocks the Public Printer | 124 |

| A General who had formed an Intimate Acquaintance with himself | 125 |

| Charles I. held up as a Model for Mr. Lincoln's Guidance in Dealing with Insurgents—Had no Head to Spare | 127 |

| Question of whether Slaves would starve if Emancipated | 127 |

| Mr. Lincoln expresses his Opinion of Rebel Leaders to Confederate Commissioners at the Peace Conference | 128 |

| Impression made upon Mr. Lincoln by Alex. H. Stephens | 129 |

| Heading a Barrel | 129 |

| A Fight, its Serious Outcome, and Mr. Lincoln's Kindly View of the Affair | 130 |

| Not always easy for Presidents to have Special Trains furnished them | 132 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Reason for not being in a Hurry to Catch the | |

| Train | 133 |

| "Something must be done in the Interest of the Dutch" | 134 |

| San Domingo Affair | 134 |

| Cabinet had shrunk up North | 135 |

| Ill Health of Candidates for the Position of Commissioner of the Sandwich Islands | 135 |

| Encouragement to Young Lawyer who lost his Case | 136 |

| Settle the Difficulty without Reference to Who commenced the Fuss | 137 |

| "Doubts about the Abutment on the Other Side" | 138 |

| Mr. Anthony J. Bleeker tells his Experience in Applying for a Position—Believed in Punishment after Death | 138 |

| Mr. Lincoln points out a Marked Trait in one of the Northern Governors | 140 |

| "Ploughed around him" | 142 |

| Revenge on Enemy | 143 |

| [xvi] | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE ANTIETAM EPISODE.—LINCOLN'S LOVE OF SONG. | |

| If a Cause of Action is Good it needs no Vindication | 144 |

| Letter from A. J. Perkins | 145 |

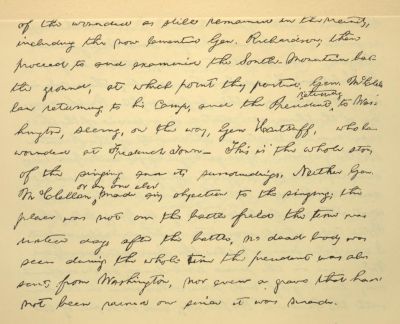

| Mr. Lincoln's Own Statement of the Antietam Affair | 147 |

| One "Little Sad Song" | 150 |

| Well Timed Rudeness of Kind Intent | 151 |

| Favorite Songs | 152 |

| Adam and Eve's Wedding Day | 152 |

| Favorite Poem: "O Why Should the Spirit of Mortal be Proud?" | 153 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| HIS LOVE OF CHILDREN. | |

| The Incident which led Mr. Lincoln to wear a Beard | 158 |

| The Knife that fairly belonged to Mr. Lincoln | 159 |

| Mr. Lincoln is introduced to the Painter of his "Beautiful Portrait" | 160 |

| Death of Mr. Lincoln's Favorite Child | 161 |

| Measures taken to break the Force of Mr. Lincoln's Grief | 162 |

| The Invasion of Tad's Theatre | 164 |

| Tad introduces some Kentucky Gentlemen | 166 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE TRUE HISTORY OF THE GETTYSBURG SPEECH. | |

| The Gettysburg Speech | 169 |

| A Modesty which scorned Eulogy for Achievements not his Own | 170 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Regret that he had not prepared the Gettysburg | |

| Speech with Greater Care | 173 |

| Mr. Everett's and Secretary Seward's Opinion of the Speech | 174 |

| The Reported Opinion of Mr. Everett | 174 |

| Had unconsciously risen to a Height above the Cultured Thought of the Period | 176 |

| Intrinsic Excellence of the Speech first discovered by European Journals | 176 |

| [xvii] | |

| How the News of Mr. Lincoln's Death was received by Other Nations | 176 |

| Origin of Phrase "Government of the People, by the People, and for the People" | 177 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| HIS UNSWERVING FIDELITY TO PURPOSE. | |

| An Intrigue to appoint a Dictator | 180 |

| "Power, Plunder, and Extended Rule" | 181 |

| Feared Nothing except to commit an Involuntary Wrong | 182 |

| President of One Part of a Divided Country—Not a Bed of Roses | 182 |

| Mr. Lincoln asserts himself | 184 |

| Demands for General Grant's Removal | 184 |

| Distance from the White House to the Capitol | 185 |

| Stoical Firmness of Mr. Lincoln in standing by General Grant | 185 |

| Letter from Mr. Lincoln to General Grant | 186 |

| The Only Occasion of a Misunderstanding between the President and General Grant | 187 |

| Special Order Relative to Trade-Permits | 188 |

| Extract from Wendell Phillips's Speech | 189 |

| Willing to abide the Decision of Time | 190 |

| Unworthy Ambition of Politicians and the Jealousies in the Army | 191 |

| Resignation of General Burnside—Appointment of Successor | 192 |

| War conducted at the Dictation of Political Bureaucracy | 193 |

| Letter to General Hooker | 194 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Treatment of the Subject of Dictatorship | 195 |

| Symphony of Bull-Frogs | 196 |

| "A Little More Light and a Little Less Noise" | 198 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| HIS TRUE RELATIONS WITH McCLELLAN. | |

| Mr. Lincoln not a Creature of Circumstances | 199 |

| Subordination of High Officials to Mr. Lincoln | 200 |

| The Condition of the Army at Beginning and Close of General McClellan's Command | 201 |

| [xviii] | |

| Mr. Lincoln wanted to "borrow" the Army if General McClellan did not want to use it | 202 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Opinion of General McClellan. A Protest denouncing the Conduct of McClellan | 203 |

| Mr. Lincoln alone Responsible to the Country for General McClellan's Appointment as Commander of the Forces at Washington | 204 |

| Confidential Relationship between Francis P. Blair and Mr. Lincoln | 205 |

| Mr. Blair's Message to General McClellan | 206 |

| General McClellan repudiates the Obvious Meaning of the Democratic Platform | 207 |

| Mr. Lincoln hopes to be "Dumped on the Right Side of the Stream" | 208 |

| Last Appeal to General McClellan's Patriotism | 208 |

| Proposition Declined | 210 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| HIS MAGNANIMITY. | |

| Public Offices in no Sense a Fund upon which to draw for the Payment of Private Accounts | 212 |

| Busy letting Rooms while the House was on Fire | 214 |

| Peremptory Order to General Meade | 214 |

| Conditions of Proposition to renounce all Claims to Presidency and throw Entire Influence in Behalf of Horatio Seymour | 215 |

| Mr. Thurlow Weed to effect Negotiation | 216 |

| Mr. Lincoln deterred from making the Magnanimous Self-Sacrifice | 217 |

| How Mr. Lincoln thought the Currency was made | 217 |

| Mr. Chase explains the System of Checks—The President impressed with Danger from this Source | 218 |

| First Proposition to Mr. Lincoln to issue Interest-Bearing Notes as Currency—The Interview between David Taylor and Secretary Chase | 220 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Honesty—Some Legal Rights and Moral Wrongs | 222 |

| Mr. Lincoln annuls the Proceedings of Court-Martial in Case of Franklin W. Smith and Brother | 222 |

| Senator Sherman omits Criticism of Lincoln | 223 |

| Release of Roger A. Pryor | 224 |

| [xix] | |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| CABINET COUNSELS. | |

| The "Trent" Affair | 227 |

| Spirit of Forgiveness (?) toward England | 229 |

| The Interview which led to the Appointment of Mr. Stanton as Secretary of War | 230 |

| Correspondence with Hon. William A. Wheeler | 231 |

| The Appointment of Mr. Stanton a Surprise to the Country | 232 |

| Mr. Stanton's Rudeness to Mr. Lincoln in 1858 | 236 |

| Mr. Lincoln abandons a Message to Congress in Deference to the Opinion of his Cabinet—Proposed Appropriation of $3,000,000 as Compensation to Owners of Liberated Slaves | 237 |

| Mr. Stanton's Refusal of Permits to go through the Lines into Insurgent Districts | 239 |

| Not Much Influence with this Administration | 239 |

| Mr. Stanton's Resignation not accepted | 239 |

| The Seven Words added by Mr. Chase to the Proclamation of Emancipation | 240 |

| Difference between "Qualified Voters" and "Citizens of the State" | 240 |

| Letter of Governor Hahn | 241 |

| Universal Suffrage One of Doubtful Propriety | 242 |

| Not in Favor of Unlimited Social Equality | 242 |

| The Conditions under which Mr. Lincoln wanted the War to Terminate | 243 |

| The Rights and Duties of the Gentleman and of the Vagrant are the Same in Time of War | 245 |

| What was to be the Disposition of the Leaders of the Rebellion | 246 |

| Mr. Lincoln and Jefferson Davis on an Imaginary Island | 247 |

| Disposition of Jefferson Davis discussed at a Cabinet Meeting | 248 |

| Principal Events of Life of Mr. Davis after the War | 249 |

| Discussing the Military Situation—Terms of Peace must emanate from Mr. Lincoln | 250 |

| Telegram to General Grant | 251 |

| Dignified Reply of General Grant | 252 |

| [xx] | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| CONFLICT BETWEEN CIVIL AND MILITARY AUTHORITY. | |

| Difficulties attending the Execution of the Fugitive Slave Law | 254 |

| Civil Authority outranked the Military | 255 |

| District Jail an Objective Point | 257 |

| Resignation of Marshal | 258 |

| Marshal's Office made a Subject of Legislation in Congress | 259 |

| A Result of Blundering Legislation | 259 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Existence embittered by Personal and Political Attacks | 260 |

| Rev. Robert Collyer and the Rustic Employee | 261 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| PLOTS AND ASSASSINATION. | |

| Conspiracy to kidnap Mr. Buchanan | 264 |

| Second Scheme of Abduction | 265 |

| Mr. Lincoln relates the Details of a Dangerous Ride | 265 |

| A Search for Mr. Lincoln | 271 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Peril during Ceremonies of his Second Inauguration—Booth's Phenomenal Audacity | 271 |

| The Polish Exile from whom Mr. Lincoln feared Assault | 273 |

| An Impatient Letter appealing to Mr. Lincoln's Prudence | 274 |

| Mr. Lincoln's high Administrative Qualities | 276 |

| But Few Persons apprehended Danger to Mr. Lincoln | 276 |

| General Grant receives the News of the Assassination of Mr. Lincoln—A Narrow Escape | 278 |

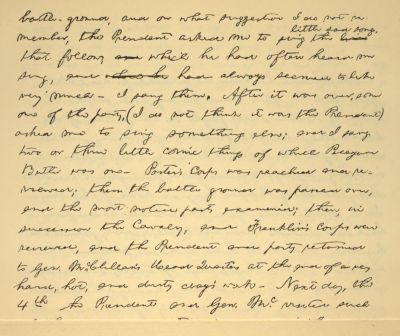

| Last Passport written by Mr. Lincoln | 280 |

| Mr. Lincoln requested to make a Promise | 280 |

| Mr. Lincoln's Farewell to his Marshal | 281 |

| Lincoln's Last Laugh | 282 |

| Willing to concede Much to Democrats | 286 |

| Eastern Shore Maryland | 287 |

| Honesty in Massachusetts and Georgia | 287 |

| [xxi] | |

| McClellan seems to be Lost | 288 |

| Battle of Antietam, Turning-point in Lincoln's Career | 289 |

| Motto for the Greenback | 289 |

| "Niggers will never be higher" | 290 |

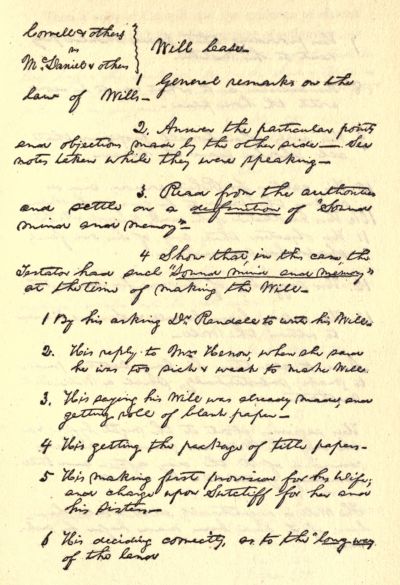

| Lincoln in a Law Case | 291 |

| Lincoln's Views of the American or Know-Nothing Party | 299 |

| Account of Arrangement for Cooper Institute Speech | 300 |

| "Rail Splitter" | 303 |

| Temperance | 305 |

| Shrewdness | 309 |

| Religion | 333 |

INDEX OF LETTERS.

Briggs, Jas. A., 300

Catron, J., 330

Davis, David, xxxii, 317, 324

Doubleday, A., 326

Douglas, S. A., 319

Faulkner, Chas. J., 327

Fell, Jesse W., 11

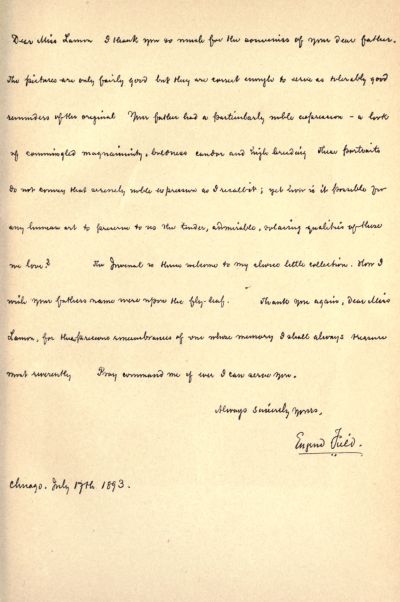

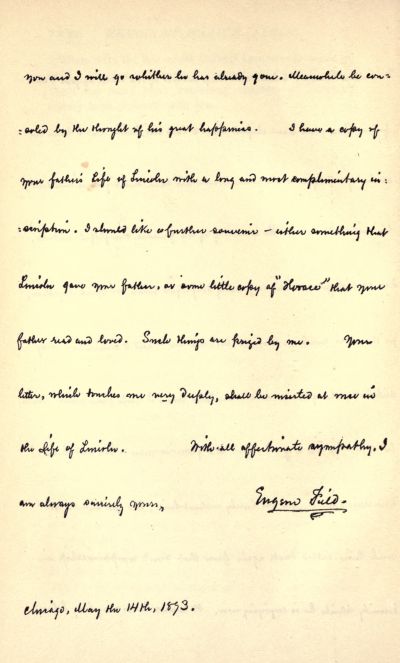

Field, Eugene, xxxv

Field, Kate, 306

Foster, Chas. H., 325

Grant, Gen., to Secy. Stanton, 252

Hanna, W. H., 317, 320, 326, 331

Harmon, O. F., 314

Hatch, O. M., 313, 316

Henderson, D. P., 331

Holt, J., 58

Hurlburt, Stephen A., 79

Kress, Jno. A., 256

Lamon, W. H., xxvi, 231, 274, 307, 333

Lemon, J. E., 319

Lincoln, A., xxxiii, xxix, 26, 106, 108, 186, 194, 241, 301, 309

Logan, S. T., xxviii, 328

McClure, A. K., vii

Murray, Bronson, 311, 312

Oglesby, R. J., 330

Perkins, A. J., 145

Pickens, Gov. F. W., 75, 78

Pleasanton, A., 289

Pope, John, 316

Scott, Winfield, 314

Seward, W. H., xxxi

Shaffer, J. W., 329

Smith, Jas. H., 312

Stanton, Ed. M., 252

Swett, Leonard, 313, 318

Taylor, Hawkins, 315, 327

Usher, Secy. J. P., v, xxv, 320, 322

Weed, Thurlow, 34

Weldon, Lawrence, xxxii, 318

Wentworth, Jno., 331

Wheeler, Wm. A., 234

Yates, Richard, xxiv

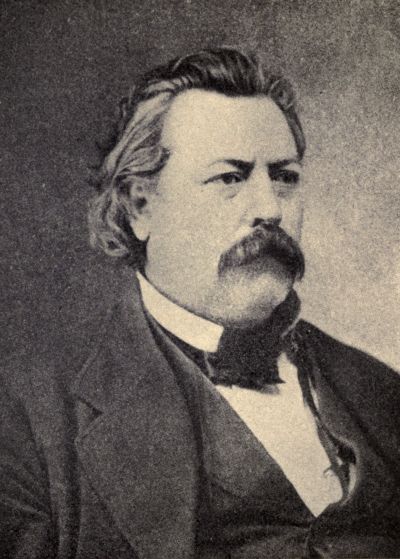

WARD HILL LAMON.

WARD HILL LAMON.

MEMOIR OF WARD H. LAMON.

Ward H. Lamon was born in Frederick County, about two miles north of Winchester, in the state of Virginia, on the 6th day of January, 1828. Two years after his birth his parents moved to Berkeley County in what is now West Virginia, near a little town called Bunker Hill, where he received a common school education. At the age of seventeen he began the study of medicine which he soon abandoned for law. When nineteen years of age he went to Illinois and settled in Danville; afterwards attending lectures at the Louisville (Ky.) Law School. Was admitted to the Bar of Kentucky in March, 1850, and in January, 1851, he was admitted to the Illinois Bar, which comprised Abraham Lincoln, Judge Stephen T. Logan, Judge David Davis, Leonard Swett, and others of that famous coterie, all of whom were his fast friends.

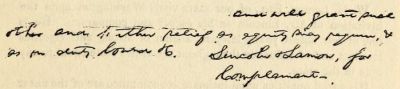

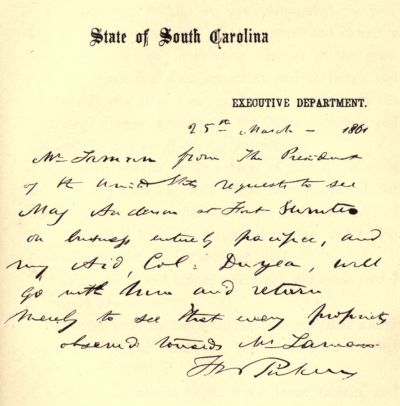

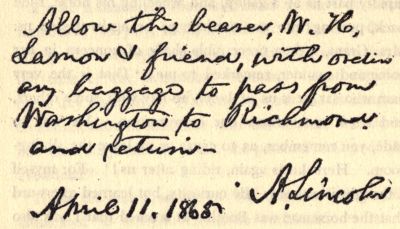

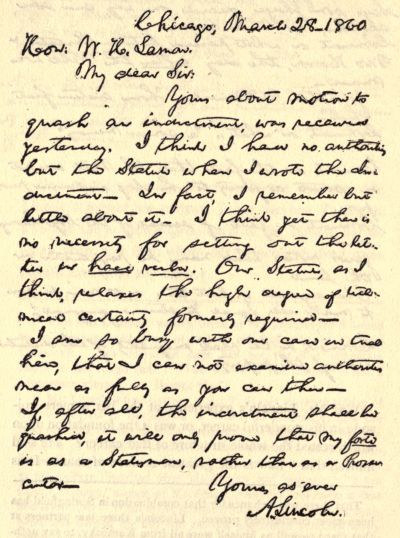

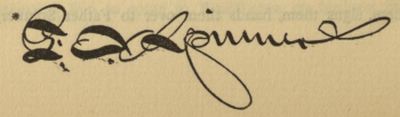

Conclusion of a Legal Document signed by Lincoln and Lamon.

Conclusion of a Legal Document signed by Lincoln and Lamon.

They all rode the circuit together, there being no railroads at that time in the State. And it has been said that, "It is doubtful if the bar of any other state of the union equalled that of the frontier state of Illinois in professional ability when Lincoln won his spurs." A legal partnership was formed between Mr. Lamon and Mr. Lincoln for the practice[xxiv] of law in the eighth District. Headquarters of this partnership was first at Danville and then at Bloomington. Was elected District Attorney for the eighth District in 1856, which office he continued to hold until called upon by Mr. Lincoln to accompany him to Washington. It was upon Mr. Lamon that Mr. Lincoln and his friends relied to see him safely to the National Capitol, when it became necessary at Harrisburg to choose one companion for the rest of the journey.[A]

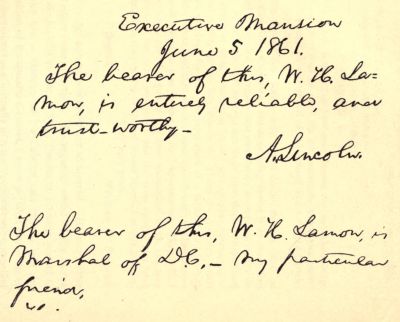

He was appointed Marshal of the District of Columbia, which position at that time was much more of a social function than it was in after years. The Marshal performed some of the ceremonies which have since been delegated to the Superintendent of Public Buildings and Grounds. He introduced people to the President on state occasions and[xxv] was the general social factotum of the Executive Mansion. The position of Marshal was not of his own choosing. Had he consulted his own taste he would have preferred some appointment in Europe.[B] It was almost settled that he was to be sent as Consul to Paris, but in deference to Mr. Lincoln's wish to have him near him in the trying times which he anticipated, he shouldered the duties of Marshal at this dangerous period, when it was one of much friction and difficulty, as slavery ruled for a hundred miles north and a thousand miles south and west of the Capitol.

After the law was passed emancipating the slaves in the District of Columbia, that territory was made, or sought to be made, the asylum for the unemancipated slaves of the States of Maryland and Virginia. Mr. Lincoln was not yet ready to issue his general emancipation proclamation; the Fugitive Slave law was still in force and was sought to be enforced. This condition of things was seized upon by many political demagogues to abuse the President over the shoulders of the Marshal. They exaggerated the truly deplorable condition of the bondmen and made execrable all officers of the Government, whose duty it became to execute laws of their own making.

The jail was at that time in the custody of the Marshal, and he was responsible for the safe keeping of twice as many criminals as his means of keeping them safely justified;[xxvi] Congress being responsible for the insufficiency of those means. To have performed the official requirements of that office in pursuance of the then existing laws and the official oath required, and at the same time given satisfaction to the radical element of the Republican party, was impossible; hence the vindictive persecution that followed which continued in the Republican party against Marshal Lamon to the end of his life.

Colonel Lamon was a strong Union man but was greatly disliked by the Abolitionists; was considered proslavery by them for permitting his subordinates to execute the old Maryland laws in reference to negroes, which had been in force since the District was ceded to the Federal Government. After an unjust attack upon him in the Senate, they at last reached the point where they should have begun, introduced a bill to repeal the obnoxious laws which the Marshal was bound by his oath of office to execute. When the fight on the Marshal was the strongest in the Senate, he sent in the following resignation to Mr. Lincoln:

Washington, D. C., Jany. 31, 1862.

Hon. A. Lincoln, President, United States:

Sir, — I hereby resign my office as Marshal for the District of Columbia. Your invariable friendship and kindness for a long course of years which you have ever extended to me impel me to give the reasons for this course. There appears to be a studious effort upon the part of the more radical portion of that party which placed you in power to pursue me with a relentless persecution, and I am now under condemnation by the United States Senate for doing what I am sure meets your approval, but by the course pursued by that honorable body I fear you will be driven to the necessity of either sustaining the action of that body, or breaking with them and sustaining me, which you cannot afford to do under the circumstances.

I appreciate your embarrassing position in the matter, and feel as unselfish in the premises as you have ever felt and acted[xxvii] towards me in the course of fourteen years of uninterrupted friendship; now when our country is in danger, I deem it but proper, having your successful administration of this Government more at heart than my own pecuniary interests, to relieve you of this embarrassment by resigning that office which you were kind enough to confide to my charge, and in doing so allow me to assure you that you have my best wishes for your health and happiness, for your successful administration of this Government, the speedy restoration to peace, and a long and useful life in the enjoyment of your present high and responsible office.

I have the honor to be

Your friend and obedient servant,

Ward H. Lamon.

Mr. Lincoln refused to accept this resignation for reasons which he partly expressed to Hon. William Kellogg, Member of Congress from Illinois, at a Presidential reception about this time. When Judge Kellogg was about to pass on after shaking the President's hand Mr. Lincoln said, "Kellogg, I want you to stay here. I want to talk to you when I have a chance. While you are waiting watch Lamon (Lamon was making the presentations at the time). He is most remarkable. He knows more people and can call more by name than any man I ever saw."

After the reception Kellogg said, "I don't know but you are mistaken in your estimate of Lamon; there are many of our associates in Congress who don't place so high an estimate on his character and have little or no faith in him whatever." "Kellogg," said Lincoln, "you fellows at the other end of the Avenue seem determined to deprive me of every friend I have who is near me and whom I can trust. Now, let me tell you, sir, he is the most unselfish man I ever saw; is discreet, powerful, and the most desperate man in emergency I have ever seen or ever expect to see. He is my friend and I am his and as long as I have these great responsibilities on me I intend to insist on his being with me, and I will stick by him at all hazards." Kellogg, seeing he[xxviii] had aroused the President more than he expected, said, "Hold on, Lincoln; what I said of our mutual friend Lamon was in jest. I am also his friend and believe with you about him. I only intended to draw you out so that I might be able to say something further in his favor with your endorsement. In the House today I defended him and will continue to do so. I know Lamon clear through." "Well, Judge," said Lincoln, "I thank you. You can say to your friends in the House and elsewhere that they will have to bring stronger proof than any I have seen yet to make me think that Hill Lamon is not the most important man to me I have around me."

Every charge preferred against the Marshal was proven groundless, but the Senators and Representatives who had joined in this inexcusable persecution ever remained his enemies as did also the radical press.[C]

The following is a sample of many letters received by Colonel Lamon about this time:—

March, 23, 1862.

... — I was rather sorry that you should have thought that I needed to see any evidence in regard to the war Grimes & Company were making on you to satisfy me as to what were the facts. No one, however, had any doubt but that they made the attack on you for doing your duty under the law. Such men as he and his coadjutors think every man ought to be willing to commit perjury or any other crime in pursuit of their abolition notions.

We suppose, however, that they mostly designed the attack on you as a blow at Lincoln and as an attempt to reach him through[xxix] his friends. I do not doubt but they would be glad to drive every personal friend to Lincoln out of Washington.

I ought to let you know, however, that you have risen more than an hundred per cent in the estimation of my wife on account of your having so acted as to acquire the enmity of the Abolitionists. I believe firmly that if we had not got the Republican nomination for him (Lincoln) the Country would have been gone. I don't know whether it can be saved yet, but I hope so....

Write whenever you have leisure.

Yours respectfully,

S. T. Logan.

Mr. Lincoln had become very unpopular with the politicians—not so with the masses, however. Members of Congress gave him a wide berth and eloquently "left him alone with his Martial Cloak around him." It pained him that he could not please everybody, but he said it was impossible. In a conversation with Lamon about his personal safety Lincoln said, "I have more reason today to apprehend danger to myself personally from my own partisan friends than I have from all other sources put together." This estrangement between him and his former friends at such a time no doubt brought him to a more confidential relation with Colonel Lamon than would have been otherwise.

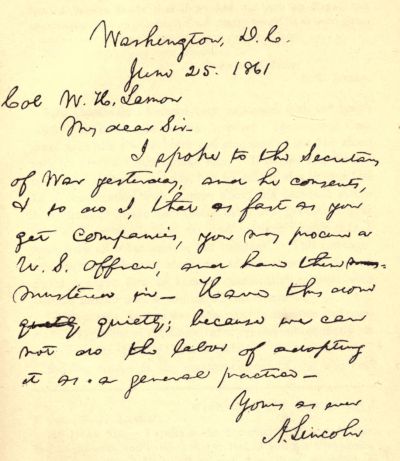

In May, 1861, Lamon was authorized to organize and command a regiment of volunteer Infantry, and subsequently his command was increased to a brigade.[D]

Raising troops at the commencement of the war cost[xxx] Colonel Lamon $22,000, for which he never asked the Government to reimburse a dollar. Mr. Lincoln urged him to put in his vouchers and receive it back, but Lamon did not want to place himself in the position that any evil-disposed person could question his integrity or charge him with having wrongfully received from the Government one dollar.

His military service in the field, however, was of short duration—from May, 1861, to December of that year—for his services were in greater demand at the Nation's Capital. He held the commission of Colonel during the war.

Colonel Lamon was charged with several important missions for Mr. Lincoln, one of the most delicate and dangerous being a confidential mission to Charleston, S. C., less than three weeks before the firing on Sumter.

At the time of the death of Mr. Lincoln, Lamon was in Richmond. It was believed by many who were familiar with Washington affairs, including Mr. Seward, Secretary of State, that had Lamon been in the city on the 14th of April, 1865, that appalling tragedy at Ford's Theatre would have been averted.

From the time of the arrival of the President-elect at Washington until just before his assassination, Lamon watched over his friend and Chief with exceeding intelligence and a fidelity that knew no rest. It has been said of Lamon that, "The faithful watch and vigil long with which he guarded Lincoln's person during those four years was seldom, if ever, equalled by the fidelity of man to man." Lamon is perhaps best known for the courage and watchful devotion with which he guarded Lincoln during the stormy days of the Civil War.

After Lincoln's death it was always distasteful to Lamon to go to the White House. He resigned his position in June following Mr. Lincoln's death in the face of the remonstrance of the Administration.

The following is a copy of a letter of Mr. Seward accepting his resignation:—

Department of State,

Washington, June 10, 1865.To Ward H. Lamon, Esq.,

Marshal of the United States

for the District of Columbia,

Washington, D. C.My Dear Sir, — The President directs me to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 8th instant, in which you tender your resignation as Marshal of the United States for the District of Columbia.

He accepts your resignation, as you desire, to take effect on Monday, the 12th instant, but in so doing deems it no more than right to say that he regrets that you should have asked him to do so. Since his advent here, he has heard from those well qualified to speak of your unwavering loyalty and of your constant personal fidelity to the late President. These are qualities which have obtained for you the reputation of a faithful and fearless public officer, and they are just such qualities as the Government can ill afford to lose in any of its Departments. They will, I doubt not, gain for you in any new occupation which you may undertake the same reputation and the same success you have obtained in the position of United States Marshal of this District.

Very truly yours,

(Signed)William H. Seward.

Colonel Lamon was never just to himself. He cared little for either fame or fortune. He regarded social fidelity as one of the highest virtues. When President Johnson wished to make him a Member of his Cabinet and offered him the position of Postmaster-General, Lamon pleaded the cause of the incumbent so effectually that the President was compelled to abandon the purpose.

Judge David Davis, many years on the U. S. Supreme Bench, and administrator of Mr. Lincoln's estate, wrote the following under date of May 23, 1865, to Hon. Wm. H. Seward, Secretary of State.

[xxxii]There is one matter of a personal nature which I wish to suggest to you. Mr. Lincoln was greatly attached to our friend Col. Ward H. Lamon. I doubt whether he had a warmer attachment to anybody, and I know that it was reciprocated. Col. Lamon has for a long time wanted to resign his office and had only held it at the earnest request of Mr. Lincoln.

Mr. Lincoln would have given him the position of Governor of Idaho. Col. Lamon is well qualified for that place. He would be popular there. He understands Western people and few men have more friends. I should esteem it as a great favor personally if you could secure the place for him. If you can't succeed nobody else can. Col. Lamon will make no effort and will use no solicitation.

He is one of the dearest friends I have in the world. He may have faults, and few of us are without them, but he is as true as steel, honorable, high minded, and never did a mean thing in his life. Excuse the freedom with which I have written.

May I beg to be remembered to your son and to your family.

Yours most truly,

David Davis.

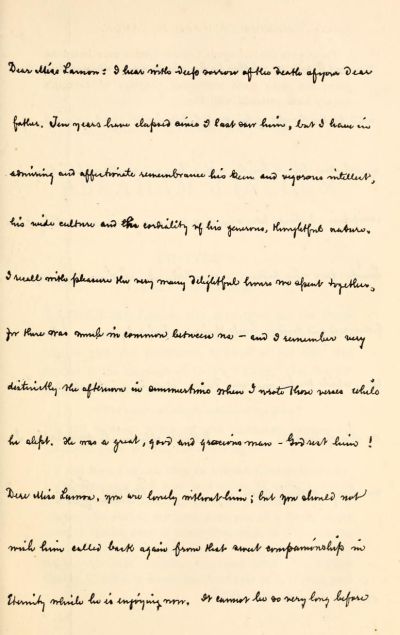

The faithfulness till death of this noble man's friendship is shown in the following letter written for him when he was dying, twenty-one years later.

Bloomington, Ill.,

June 22, 1886.Col. W. H. Lamon:

Dear Sir, — On my return from Washington about a month since Judge Davis said to me that he had a long letter from you which he intended to answer as soon as he was able to do so. Since that time the Judge has been declining in health until he is now beyond all capability of writing. I have not seen him for three weeks until yesterday morning when I found him in lowest condition of life. Rational when aroused but almost unconscious of his surroundings except when aroused.

He spoke in the kindest terms of you and was much annoyed because an answer to your letter was postponed. He requested me this morning through Mrs. Davis to write you, while Mrs. Davis handed me the letter. I have not read it as it is a personal letter to the Judge. I don't know that I can say any more.[xxxiii] It was one of the saddest sights of my life to see the best and truest friend I ever had emaciated with disease, lingering between life and death. Before this reaches you the world may know of his death. I understood Mrs. Davis has written you.

Very truly,

Lawrence Weldon.

In striking contrast to this beautiful friendship is another which one would pronounce equally strong were he to judge the man who professed it from his letters to Lamon, covering a period of twenty-five years, letters filled throughout with expressions of the deepest trust, love, admiration, and even gratitude; but in a book published last November [1910] there appear letters from this same man to one of Lamon's bitterest enemies. In one he says, "Lamon was no solid firm friend of Lincoln." Let us hope he was sincere when he expressed just the opposite sentiment to Lamon, for may it not have been his poverty and not his will which consented to be thus "interviewed." He alludes twice in this same correspondence to his poverty, once when he gives as his reason for selling something he regretted to have sold that "I was a poor devil and had to sell to live," and again, "—— are you getting rich? I am as poor as Job's turkey."

One of Lamon's friends describes him:—

"Of herculean proportions and almost fabulous strength and agility, Lamon never knew what fear was and in the darkest days of the war he never permitted discouragement to affect his courage or weaken his faith in the final success of the Nation. Big-hearted, genial, generous, and chivalrous, his memory will live long in the land which he served so well."

Leonard Swett wrote in the "North American Review":—

"Lamon was all over a Virginian, strong, stout and athletic—a Hercules in stature, tapering from his broad shoulders to his heels, and the handsomest man physically I ever saw. He was six feet high and although prudent and cautious, was thoroughly courageous[xxxiv] and bold. He wore that night [when he accompanied Lincoln from Harrisburg to Washington] two ordinary pistols, two derringers and two large knives. You could put no more elements of attack or defence in a human skin than were in Lamon and his armory on that occasion.... Mr. Lincoln knew the shedding the last drop of blood in his defence would be the most delightful act of Lamon's life, and that in him he had a regiment armed and drilled for the most efficient service."

The four or five thousand letters left by Colonel Lamon show that his influence was asked on almost every question, and show that Mr. Lincoln was more easily reached through Colonel Lamon than by any other one man; even Mrs. Lincoln herself asked Lamon's influence with her husband. Extracts from some of these letters may be found at the end of this volume. They breathe the real atmosphere of other days.

After his resignation as Marshal, he resumed the practice of law in company with Hon. Jeremiah S. Black and his son, Chauncey F. Black.

Broken in health and in fortune, he went to Colorado in 1879, where he remained seven years. It was here that the beautiful friendship began between Colonel Lamon and Eugene Field. This friendship meant much to both of them. To Eugene Field, then one of the editors of the Denver "Tribune," who had only a boyhood recollection of Lincoln, it meant much to study the history of the War and the martyred President with one who had seen much of both. To Colonel Lamon it was a solace and a tonic, this association with one in whom sentiment and humor were so delicately blended.

One little incident of this friendship is worth the telling because of the pathetic beauty of the verses which it occasioned.

One day when Field dropped in to see Lamon he found him asleep on the floor. (To take a nap on the floor was a habit of both Lamon and Lincoln, perhaps because they[xxxv] both experienced difficulty in finding lounges suited to their length—Lamon was six feet two inches, Lincoln two inches taller.) Field waited some time thinking Lamon would wake up, but he did not; so finally Field penciled the following verses on a piece of paper, pinned it to the lapel of Lamon's coat, and quietly left:—

And dreamed sweet dreams upon the floor,

Into your hiding place I crept

And heard the music of your snore.

Who pipes as music'ly as thou—

Who loses self in slumbers deep

As you, O happy man, do now,

From troublous pangs and vain ado;

So ever may thy slumbers be—

So ever be thy conscience too!

Shall smooth the wrinkles from thy brow,

May God on high as gently guard

Thy slumbering soul as I do now.

This incident occurred in the summer of 1882. Eleven years after Colonel Lamon lay dying. He was conscious to the last moment, but for the last sixteen hours he had lost the power of speech. His daughter watched him for those sixteen hours, hoping every moment he would be able to speak. She was so stunned during this long watch that she could not utter a prayer to comfort her father's soul, but just before the end came, the last lines of the little poem came to her like an inspiration which she repeated aloud to her dying father:

Shall smooth the wrinkles from thy brow,

May God on high as gently guard

Thy slumbering soul as I do now.

[xxxvi]These were the last words Colonel Lamon ever heard on earth. He died at eleven o'clock on the night of May 7th, 1893; and many most interesting chapters of Lincoln's history have perished with him.

RECOLLECTIONS

OF

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

CHAPTER I.

EARLY ACQUAINTANCE.

When Mr. Lincoln was nominated for the Presidency in 1860, a campaign book-maker asked him to give the prominent features of his life. He replied in the language of Gray's "Elegy," that his life presented nothing but

"The short and simple annals of the poor."

He had, however, a few months previously, written for his friend Jesse W. Fell the following:—

I was born Feb. 12, 1809, in Harden County, Kentucky. My parents were both born in Virginia, of undistinguished families—second families, perhaps I should say. My mother, who died in my tenth year, was of a family of the name of Hanks, some of whom now reside in Adams, some others in Macon counties, Illinois—My paternal grandfather, Abraham Lincoln, emigrated from Rockingham County, Virginia, to Kentucky, about 1781 or 2, where, a year[10] or two later, he was killed by indians,—not in battle, but by stealth, when he was laboring to open a farm in the forest—His ancestors, who were quakers, went to Virginia from Berks County, Pennsylvania—An effort to identify them with the New England family of the same name ended in nothing more definite, than a similarity of Christian names in both families, such as Enoch, Levi, Mordecai, Solomon, Abraham, and the like—

My father, at the death of his father, was but six years of age; and he grew up, literally without education—He removed from Kentucky to what is now Spencer county, Indiana, in my eighth year—We reached our new home about the time the State came into the Union—It was a wild region, with many bears and other wild animals still in the woods—There I grew up—There were some schools, so called; but no qualification was ever required of a teacher, beyond "readin, writin, and cipherin" to the Rule of Three—If a straggler supposed to understand latin happened to sojourn in the neighborhood, he was looked upon as a wizzard—There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education. Of course when I came of age I did not know much—Still, somehow, I could read, write, and cipher to the Rule of Three; but that was all—I have not been to school since—The little advance I now have upon this store of education, I have picked up from time to time under the pressure of necessity—

I was raised to farm work, which I continued till I was twenty two—At twenty one I came to Illinois, and passed the first year in Macon county—Then I got to New-Salem at that time in Sangamon, now in Menard county, where I remained a year as a sort of Clerk in a store—Then came the Black Hawk war; and I was elected a Captain of Volunteers—a success which gave me more pleasure than any I have had since—I went the campaign, was elected, ran for the Legislature the same year[11] (1832) and was beaten—the only time I ever have been beaten by the people—The next, and three succeeding biennial elections, I was elected to the Legislature—I was not a candidate afterwards. During this Legislative period I had studied law, and removed to Springfield to practice it—In 1846 I was once elected to the lower House of Congress—Was not a candidate for re-election—From 1849 to 1854, both inclusive, practiced law more assiduously than ever before—Always a whig in politics; and generally on the whig electoral tickets, making active canvasses—I was losing interest in politics, when the repeal of the Missouri Compromise aroused me again—What I have done since then is pretty well known—

If any personal description of me is thought desirable, it may be said, I am, in height, six feet, four inches, nearly; lean in flesh, weighing, on an average, one hundred and eighty pounds; dark complexion, with coarse black hair, and grey eyes—No other marks or brands recollected—

Yours very truly

A. Lincoln.J. W. Fell, Esq.

Washington, D. C., March 20, 1872.

We the undersigned hereby certify that the foregoing statement is in the hand-writing of Abraham Lincoln.

David Davis.

Lyman Trumbull.

Charles Sumner.[E]

[12]Were I to say in this polite age that Abraham Lincoln was born in a condition of life most humble and obscure, and that he was surrounded by circumstances most unfavorable to culture and to the development of that nobility and purity which his wonderful character afterward displayed, it would shock the fastidious and super-fine sensibilities of the average reader, would be regarded as prima facie evidence of felonious intent, and would subject me to the charge of being inspired by an antagonistic[13] animus. In justice to the truth of history, however, it must be acknowledged that such are the facts concerning this great man, regarding whom nothing should be concealed from public scrutiny, either in the surroundings of his birth, his youth, his manhood, or his private and public life and character. Let all the facts concerning him be known, and he will appear brighter and purer by the test.

It may well be said of him that he is probably the only man, dead or living, whose true and faithful life could be written and leave the subject more ennobled by the minutiæ of the record. His faults are but "the shadows which his virtues cast." It is my purpose in these recollections to give the reader a closer view of the great war President than is afforded by current biographies, which deal mainly with the outward phases of his life; and in carrying out this purpose I will endeavor to present that many-sided man in those relations where his distinguishing traits manifest themselves most strongly.

With the grandeur of his figure in history, with his genius and his achievements as the model statesman and chief magistrate, all men are now familiar; but there yet remain to be sketched many phases of his inner life. Many of the incidents related in these sketches came to my knowledge through my long-continued association with him both in his private and public life; therefore, if the Ego shall seem at times pushed forward to undue prominence, it will be because of its convenience, or[14] rather necessity, certainly not from any motive of self-adulation.

My personal acquaintance with Mr. Lincoln dates back to the autumn of 1847. In that year, attracted by glowing accounts of material growth and progress in that part of the West, I left my home in what was then Berkeley County, Virginia, and settled at Danville, Vermillion County, Illinois. That county and Sangamon, including Springfield, the new capital of the State, were embraced in the Eighth Judicial Circuit, which at that early day consisted of fourteen counties. It was then the custom of lawyers, like their brethren of England, "to ride the circuit." By that circumstance the people came in contact with all the lawyers in the circuit, and were enabled to note their distinguishing traits. I soon learned that the man most celebrated, even in those pioneer days, for oddity, originality, wit, ability, and eloquence in that region of the State was Abraham Lincoln. My great curiosity to see him was gratified soon after I took up my residence at Danville.

I was introduced to Mr. Lincoln by the Hon. John T. Stuart, for some years his partner at Springfield. After a comical survey of my fashionable toggery,—my swallow-tail coat, white neck-cloth, and ruffled shirt (an astonishing outfit for a young limb of the law in that settlement),—Mr. Lincoln said: "And so you are a cousin of our friend John J. Brown; he told me you were coming. Going to try your hand at the law, are you? I should know at a glance that you were a Virginian; but[15] I don't think you would succeed at splitting rails. That was my occupation at your age, and I don't think I have taken as much pleasure in anything else from that day to this."

I assured him, perhaps as a sort of defence against the eloquent condemnation implied in my fashionable clawhammer, that I had done a deal of hard manual labor in my time. Much amused at this solemn declaration, Mr. Lincoln said: "Oh, yes; you Virginians shed barrels of perspiration while standing off at a distance and superintending the work your slaves do for you. It is different with us. Here it is every fellow for himself, or he doesn't get there."

Mr. Lincoln soon learned, however, that my detestation of slave labor was quite as pronounced as his own, and from that hour we were friends. Until the day of his death it was my pleasure and good fortune to retain his confidence unshaken, as he retained my affection unbroken.

I was his local partner, first at Danville, and afterward at Bloomington. We rode the circuit together, traveling by buggy in the dry seasons and on horse-back in bad weather, there being no railroads then in that part of the State. Mr. Lincoln had defeated that redoubtable champion of pioneer Methodism, the Rev. Peter Cartwright, in the last race for Congress. Cartwright was an oddity in his way, quite as original as Lincoln himself. He was a foeman worthy of Spartan steel, and Mr. Lincoln's fame was greatly enhanced by his victory over the famous[16] preacher. Whenever it was known that Lincoln was to make a speech or argue a case, there was a general rush and a crowded house. It mattered little what subject he was discussing,—Lincoln was subject enough for the people. It was Lincoln they wanted to hear and see; and his progress round the circuit was marked by a constantly recurring series of ovations.

Mr. Lincoln was from the beginning of his circuit-riding the light and life of the court. The most trivial circumstance furnished a back-ground for his wit. The following incident, which illustrates his love of a joke, occurred in the early days of our acquaintance. I, being at the time on the infant side of twenty-one, took particular pleasure in athletic sports. One day when we were attending the circuit court which met at Bloomington, Ill., I was wrestling near the court house with some one who had challenged me to a trial, and in the scuffle made a large rent in the rear of my trousers. Before I had time to make any change, I was called into court to take up a case. The evidence was finished. I, being the Prosecuting Attorney at the time, got up to address the jury. Having on a somewhat short coat, my misfortune was rather apparent. One of the lawyers, for a joke, started a subscription paper which was passed from one member of the bar to another as they sat by a long table fronting the bench, to buy a pair of pantaloons for Lamon,—"he being," the paper said, "a poor but worthy young man." Several put down their names with some ludicrous subscription, and finally the paper[17] was laid by some one in front of Mr. Lincoln, he being engaged in writing at the time. He quietly glanced over the paper, and, immediately taking up his pen, wrote after his name, "I can contribute nothing to the end in view."

Although Mr. Lincoln was my senior by eighteen years, in one important particular I certainly was in a marvelous degree his acknowledged superior. One of the first things I learned after getting fairly under way as a lawyer was to charge well for legal services,—a branch of the practice that Mr. Lincoln never could learn. In fact, the lawyers of the circuit often complained that his fees were not at all commensurate with the service rendered. He at length left that branch of the business wholly to me; and to my tender mercy clients were turned over, to be slaughtered according to my popular and more advanced ideas of the dignity of our profession. This soon led to serious and shocking embarrassment.

Early in our practice a gentleman named Scott placed in my hands a case of some importance. He had a demented sister who possessed property to the amount of $10,000, mostly in cash. A "conservator," as he was called, had been appointed to take charge of the estate, and we were employed to resist a motion to remove the conservator. A designing adventurer had become acquainted with the unfortunate girl, and knowing that she had money, sought to marry her; hence the motion. Scott, the brother and conservator, before we[18] entered upon the case, insisted that I should fix the amount of the fee. I told him that it would be $250, adding, however, that he had better wait; it might not give us much trouble, and in that event a less amount would do. He agreed at once to pay $250, as he expected a hard contest over the motion.

The case was tried inside of twenty minutes; our success was complete. Scott was satisfied, and cheerfully paid over the money to me inside the bar, Mr. Lincoln looking on. Scott then went out, and Mr. Lincoln asked, "What did you charge that man?" I told him $250. Said he: "Lamon, that is all wrong. The service was not worth that sum. Give him back at least half of it."

I protested that the fee was fixed in advance; that Scott was perfectly satisfied, and had so expressed himself. "That may be," retorted Mr. Lincoln, with a look of distress and of undisguised displeasure, "but I am not satisfied. This is positively wrong. Go, call him back and return half the money at least, or I will not receive one cent of it for my share."

I did go, and Scott was astonished when I handed back half the fee.

This conversation had attracted the attention of the lawyers and the court. Judge David Davis, then on our circuit bench, called Mr. Lincoln to him. The judge never could whisper, but in this instance he probably did his best. At all events, in attempting to whisper to Mr. Lincoln he trumpeted his rebuke in about these[19] words, and in rasping tones that could be heard all over the court room: "Lincoln, I have been watching you and Lamon. You are impoverishing this bar by your picayune charges of fees, and the lawyers have reason to complain of you. You are now almost as poor as Lazarus, and if you don't make people pay you more for your services you will die as poor as Job's turkey!"

Judge O. L. Davis, the leading lawyer in that part of the State, promptly applauded this malediction from the bench; but Mr. Lincoln was immovable. "That money," said he, "comes out of the pocket of a poor, demented girl, and I would rather starve than swindle her in this manner."

That evening the lawyers got together and tried Mr. Lincoln before a moot tribunal called "The Ogmathorial Court." He was found guilty and fined for his awful crime against the pockets of his brethren of the bar. The fine he paid with great good humor, and then kept the crowd of lawyers in uproarious laughter until after midnight. He persisted in his revolt, however, declaring that with his consent his firm should never during its life, or after its dissolution, deserve the reputation enjoyed by those shining lights of the profession, "Catch 'em and Cheat 'em."

In these early days Mr. Lincoln was once employed in a case against a railroad company in Illinois. The case was concluded in his favor, except as to the pronouncement of judgment. Before this was done, he rose and[20] stated that his opponents had not proved all that was justly due to them in offset, and proceeded to state briefly that justice required that an allowance should be made against his client for a certain amount. The court at once acquiesced in his statement, and immediately proceeded to pronounce judgment in accordance therewith. He was ever ready to sink his selfish love of victory as well as his partiality for his client's favor and interest for the sake of exact justice.

In many of the courts on the circuit Mr. Lincoln would be engaged on one side or the other of every case on the docket, and yet, owing to his low charges and the large amount of professional work which he did for nothing, at the time he left Springfield for Washington to take the oath of office as President of the United States he was not worth more than seven thousand dollars,—his property consisting of the house in which he had lived, and eighty acres of land on the opposite side of the river from Omaha, Neb. This land he had entered with his bounty land-warrant obtained for services in the Black Hawk War.[1]

Mr. Lincoln was always simple in his habits and tastes. He was economical in everything, and his wants were few. He was a good liver; and his family, though not extravagant, were much given to entertainments, and saw and enjoyed many ways of spending money not observable by him. After all his inexpensive habits, and a long life of successful law practice, he was reduced to the necessity of borrowing money to defray expenses for[21] the first months of his residence at the White House. This money he repaid after receiving his salary as President for the first quarter.

A few months after meeting Mr. Lincoln, I attended an entertainment given at his residence in Springfield. After introducing me to Mrs. Lincoln, he left us in conversation. I remarked to her that her husband was a great favorite in the eastern part of the State, where I had been stopping. "Yes," she replied, "he is a great favorite everywhere. He is to be President of the United States some day; if I had not thought so I never would have married him, for you can see he is not pretty. But look at him! Doesn't he look as if he would make a magnificent President?"

"Magnificent" somewhat staggered me; but there was, without appearing ungallant, but one reply to make to this pointed question. I made it, but did so under a mental protest, for I am free to admit that he did not look promising for that office; on the contrary, to me he looked about as unpromising a candidate as I could well imagine the American people were ever likely to put forward. At that time I felt convinced that Mrs. Lincoln was running Abraham beyond his proper distance in that race. I did not thoroughly know the man then; afterward I never saw the time when I was not willing to apologize for my misguided secret protest. Mrs. Lincoln, from that day to the day of his inauguration, never wavered in her faith that her hopes in this respect would be realized.

[22]In 1858, when Mr. Lincoln and Judge Douglas were candidates for the United States Senate, and were making their celebrated campaign in Illinois, General McClellan was Superintendent of the Illinois Central Railroad, and favored the election of Judge Douglas. At all points on the road where meetings between the two great politicians were held, either a special train or a special car was furnished to Judge Douglas; but Mr. Lincoln, when he failed to get transportation on the regular trains in time to meet his appointments, was reduced to the necessity of going as freight. There being orders from headquarters to permit no passenger to travel on freight trains, Mr. Lincoln's persuasive powers were often brought into requisition. The favor was granted or refused according to the politics of the conductor.

On one occasion, in going to meet an appointment in the southern part of the State,—that section of Illinois called Egypt,—Mr. Lincoln and I, with other friends, were traveling in the "caboose" of a freight train, when we were switched off the main track to allow a special train to pass in which Mr. Lincoln's more aristocratic rival was being conveyed. The passing train was decorated with banners and flags, and carried a band of music which was playing "Hail to the Chief." As the train whistled past, Mr. Lincoln broke out in a fit of laughter and said, "Boys, the gentleman in that car evidently smelt no royalty in our carriage."

On arriving at the point where these two political[23] gladiators were to test their strength, there was the same contrast between their respective receptions. The judge was met at the station by the distinguished Democratic citizens of the place, who constituted almost the whole population, and was marched to the camping ground to the sound of music, shouts from the populace, and under floating banners borne by his enthusiastic admirers. Mr. Lincoln was escorted by a few Republican politicians; no enthusiasm was displayed, no music greeted his ears, nor, in fact, any other sound except the warble of the bull-frogs in a neighboring swamp. The signs and prospects for Mr. Lincoln's election by the support of the people looked gloomy indeed.

Judge Douglas spoke first, and so great was the enthusiasm excited by his speech that Mr. Lincoln's friends became apprehensive of trouble. When spoken to on the subject he said: "I am not going to be terrified by an excited populace, and hindered from speaking my honest sentiments upon this infernal subject of human slavery." He rose, took off his hat, and stood before that audience for a considerable space of time in a seemingly reflective mood, looking over the vast throng of people as if making a preliminary survey of their tendencies. He then bowed, and commenced by saying: "My fellow-citizens, I learn that my friend Judge Douglas said in a public speech that I, while in Congress, had voted against the appropriation for supplies to the Mexican soldiers during the late war. This, fellow-citizens, is a perversion of the facts. It is true that I was opposed to[24] the policy of the Administration in declaring war against Mexico[2]; but when war was declared, I never failed to vote for the support of any proposition looking to the comfort of our poor fellows who were maintaining the dignity of our flag in a war that I thought unnecessary and unjust."[F] He gradually became more and more excited; his voice thrilled and his whole frame shook. I was at the time sitting on the stand beside Hon. O. B. Ficklin, who had served in Congress with Mr. Lincoln in 1847. Mr. Lincoln reached back and took Ficklin by the coat-collar, back of his neck, and in no gentle manner lifted him from his seat as if he had been a kitten, and said: "Fellow-citizens, here is Ficklin, who was at that time in Congress with me, and he knows it is a lie." He shook Ficklin until his teeth chattered. Fearing that he would shake Ficklin's head off, I grasped Mr. Lincoln's hand and broke his grip. Mr. Ficklin sat down, and Lincoln continued his address.

After the speaking was over, Mr. Ficklin, who had been opposed to Lincoln in politics, but was on terms of[25] warm personal friendship with him, turned to him and said: "Lincoln, you nearly shook all the Democracy out of me to-day."

Mr. Lincoln replied: "That reminds me of what Paul said to Agrippa, which in language and substance I will formulate as follows: I would to God that such Democracy as you folks here in Egypt have were not only almost, but altogether shaken out of, not only you, but all that heard me this day, and that you would all join in assisting in shaking off the shackles of the bondmen by all legitimate means, so that this country may be made free as the good Lord intended it."

Ficklin continued: "Lincoln, I remember of reading somewhere in the same book from which you get your Agrippa story, that Paul, whom you seem to desire to personate, admonished all servants (slaves) to be obedient to them that are their masters according to the flesh, in fear and trembling. It would seem that neither our Saviour nor Paul saw the iniquity of slavery as you and your party do. But you must not think that where you fail by argument to convince an old friend like myself and win him over to your heterodox abolition opinions, you are justified in resorting to violence such as you practiced on me to-day. Why, I never had such a shaking up in the whole course of my life. Recollect that that good old book that you quote from somewhere says in effect this, 'Woe be unto him who goeth to Egypt for help, for he shall fall. The holpen shall fall, and they shall all fall together.' The next thing we know, Lincoln,[26] you and your party will be advocating a war to kill all of us pro-slavery people off."

"No," said Lincoln, "I will never advocate such an extremity; but it will be well for you folks if you don't force such a necessity on the country."

Lincoln then apologized for his rudeness in jostling the muscular Democracy of his friend, and they separated, each going his own way, little thinking then that what they had just said in badinage would be so soon realized in such terrible consequences to the country.

The following letter shows Lincoln's view of the political situation at that time:—

Springfield, June 11, 1858.

W. H. Lamon, Esq.:

My dear Sir, — Yours of the 9th written at Joliet is just received. Two or three days ago I learned that McLean had appointed delegates in favor of Lovejoy, and thenceforward I have considered his renomination a fixed fact. My opinion—if my opinion is of any consequence in this case, in which it is no business of mine to interfere—remains unchanged, that running an independent candidate against Lovejoy will not do; that it will result in nothing but disaster all round. In the first place, whoever so runs will be beaten and will be spotted for life; in the second place, while the race is in progress, he will be under the strongest temptation to trade with the Democrats, and to favor the election of certain of their friends to the Legislature; thirdly, I shall be held responsible for it, and Republican members of the Legislature, who are partial to Lovejoy, will for that purpose oppose us; and, lastly, it will in the end lose us the District altogether. There is no safe way but a convention; and if in that convention, upon a common platform which all are willing to stand upon, one who has been known as an[27] Abolitionist, but who is now occupying none but common ground, can get the majority of the votes to which all look for an election, there is no safe way but to submit.

As to the inclination of some Republicans to favor Douglas, that is one of the chances I have to run, and which I intend to run with patience.

I write in the court room. Court has opened, and I must close.

Yours as ever,

(Signed) A. Lincoln.

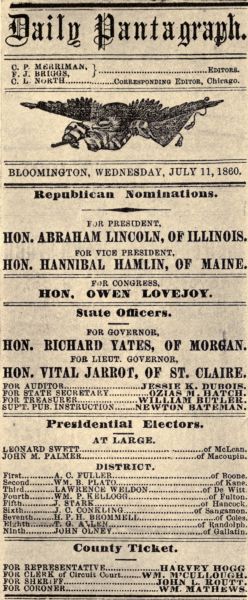

During this senatorial campaign in 1858, Hon. James G. Blaine predicted in a letter, which was extensively published, that Douglas would beat Lincoln for the United States Senate, but that Lincoln would beat Douglas for President in 1860. Mr. Lincoln cut out the paragraph of the letter containing this prediction, and placed it in his pocket-book, where I have no doubt it was found after his death, for only a very short time before that event I saw it in his possession.[3]

After Mr. Lincoln's election he was sorely beset by rival claimants for the spoils of office in his own State, and distracted by jealousies among his own party adherents. The State was divided so far as the Republican party was concerned into three cliques or factions. The Chicago faction was headed by Norman B. Judd and Ebenezer Peck, the Bloomington faction by Judge David Davis, Leonard Swett, and others, and that of Springfield by J. K. Dubois, O. M. Hatch, William Butler, and others; and however anxious Mr. Lincoln might be to honor his State by a Cabinet appointment, he was powerless[28] to do so without incurring the hostility of the factions from which he could not make a selection. Harmony was, however, in a large measure preserved among the Republican politicians by sending Judd as Minister to Prussia, and by anticipating a place on the Supreme Bench for Judge Davis. Swett wanted nothing, and middle Illinois was satisfied. Springfield controlled the lion's share of State patronage, and satisfaction was given all round as far as circumstances would allow.

Between the time of Mr. Lincoln's election and the 11th of February, 1861, he spent his time in a room in the State House which was assigned to him as an office. Young Mr. Nicolay, a very clever and competent clerk, was lent to him by the Secretary of State to do his writing. During this time he was overrun with visitors from all quarters of the country,—some to assist in forming his Cabinet, some to direct how patronage should be distributed, others to beg for or demand personal advancement. So painstaking was he, that every one of the many thousand letters which poured in upon him was read and promptly answered. The burden of the new and overwhelming labor came near prostrating him with serious illness.

Some days before his departure for Washington, he wrote to me at Bloomington that he desired to see me at once. I went to Springfield, and Mr. Lincoln said to me: "Hill, on the 11th I go to Washington, and I want you to go along with me. Our friends have already asked me to send you as Consul to Paris. You know I[29] would cheerfully give you anything for which our friends may ask or which you may desire, but it looks as if we might have war. In that case I want you with me. In fact, I must have you. So get yourself ready and come along. It will be handy to have you around. If there is to be a fight, I want you to help me to do my share of it, as you have done in times past. You must go, and go to stay."

CHAPTER II.

JOURNEY FROM SPRINGFIELD TO WASHINGTON.

On the 11th of February, 1861, the arrangements for Mr. Lincoln's departure from Springfield were completed. It was intended to occupy the time remaining between that date and the 4th of March with a grand tour from State to State and city to city. Mr. Wood, "recommended by Senator Seward," was the chief manager. He provided special trains, to be preceded by pilot engines all the way through.

It was a gloomy day: heavy clouds floated overhead, and a cold rain was falling. Long before eight o'clock, a great mass of people had collected at the station of the Great Western Railway to witness the event of the day. At precisely five minutes before eight, Mr. Lincoln, preceded by Mr. Wood, emerged from a private room in the station, and passed slowly to the car, the people falling back respectfully on either side, and as many as possible shaking his hand. Having reached the train he ascended the rear platform, and, facing the throng which had closed around him, drew himself up to his full height, removed his hat, and stood for several seconds in profound silence. His eye roved sadly over that sea of upturned faces; and he thought he read in them again the[31] sympathy and friendship which he had often tried, and which he never needed more than he did then. There was an unusual quiver on his lip, and a still more unusual tear on his furrowed cheek. His solemn manner, his long silence, were as full of melancholy eloquence as any words he could have uttered. Of what was he thinking? Of the mighty changes which had lifted him from the lowest to the highest estate in the nation; of the weary road which had brought him to this lofty summit; of his poverty-stricken boyhood; of his poor mother lying beneath the tangled underbrush in a distant forest? Whatever the particular character of his thoughts, it is evident that they were retrospective and painful. To those who were anxiously waiting to catch words upon which the fate of the nation might hang, it seemed long until he had mastered his feelings sufficiently to speak. At length he began in a husky tone of voice, and slowly and impressively delivered his farewell to his neighbors. Imitating his example, every man in the crowd stood with his head uncovered in the fast-falling rain.

"Friends, no one who has never been placed in a like position can understand my feelings at this hour, nor the oppressive sadness I feel at this parting. For more than a quarter of a century I have lived among you, and during all that time I have received nothing but kindness at your hands. Here I have lived from my youth, until now I am an old man. Here the most sacred ties of earth were assumed; here all my children were born; and here one of them lies buried. To you, dear friends, I owe all that I have, all that I am.[32] 'All the strange, checkered past seems to crowd now upon my mind.' To-day I leave you. I go to assume a task more difficult than that which devolved upon Washington. Unless the great God, who assisted him, shall be with me and aid me, I must fail; but if the same omniscient mind and almighty arm that directed and protected him shall guide and support me, I shall not fail,—I shall succeed. Let us all pray that the God of our fathers may not forsake us now. To Him I commend you all. Permit me to ask that, with equal security and faith, you will invoke His wisdom and guidance for me. With these few words I must leave you,—for how long I know not. Friends, one and all, I must now bid you an affectionate farewell."