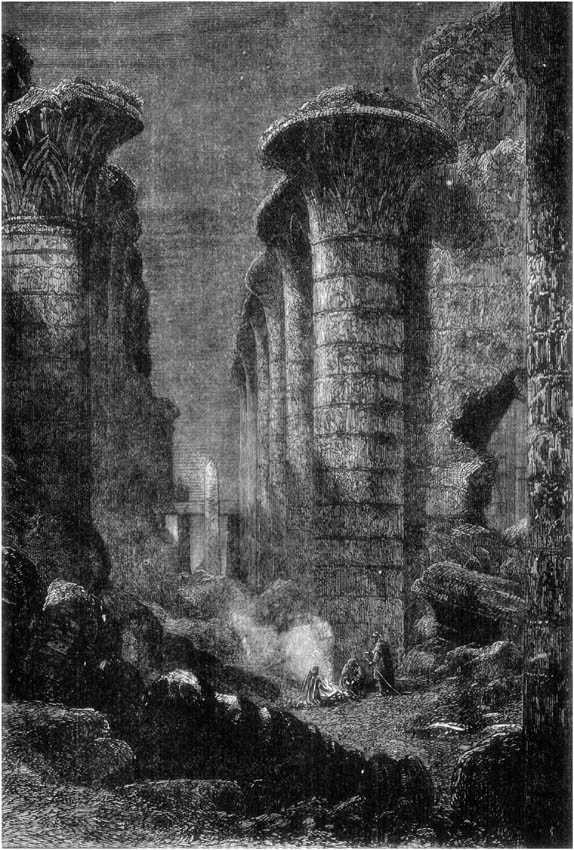

Painted by J.M.W. Turner, R.A. Engraved & Printed by Illman Brothers.

THE PALACE OF THE CAESARSToList

MUSEUM

OF

ANTIQUITY

A DESCRIPTION OF

ANCIENT LIFE:

THE

EMPLOYMENTS, AMUSEMENTS, CUSTOMS AND HABITS,

THE CITIES, PALACES, MONUMENTS AND TOMBS,

THE LITERATURE AND FINE ARTS

OF 3,000 YEARS AGO.

BY

L.W. YAGGY, M.S.,

AND

T.L. HAINES, A.M.,

AUTHORS OF THE "ROYAL PATH OF LIFE,"

"OUR HOME COUNSELOR,"

"LITTLE GEMS."

ILLUSTRATED.

MADISON, WIS.:

J.B. FURMAN & CO.

WESTERN PUBLISHING HOUSE, CHICAGO, ILL.

1884.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1880 by

L.W. Yaggy & T.L. Haines,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D.C.

[iii]

PREFACE.

Egypt, Greece and Italy were the fountain heads of our civilization and the source of our knowledge; to them we can trace, link by link, the origin of all that is ornamental, graceful and beautiful. It is therefore a matter of greatest interest to get an intimate knowledge of the original state, and former perfection, the grandeur, magnificence and high civilization of these countries, as well as of the homes, the private and domestic life, the schools, churches, rites, ceremonies, &c.

The many recent excavations in Troy, Nineveh, Babylon and the uncovering of the City of Pompeii, with its innumerable treasures, the unfolding of the long-hoarded secrets, have revealed information for volumes of matter. But works that treat on the various subjects of antiquity are, for the most part, not only costly and hard to procure, but also far too voluminous. The object of this work is to condense into the smallest possible compass the essence of information which usually runs through many volumes, and place it into a practical form for the common reader. We hope, however, that this work will give the reader a greater longing to extend his inquiries into these most interesting subjects, so rich in everything that can refine the taste, enlarge the understanding and improve the heart. It has been our object, so far as possible, to avoid every expression of opinion, whether our own or that of any school of thinkers, and to supply first, facts, and secondly, careful references by which the citations of those facts, may be verified, and the inferences from them traced by the reader himself, to their legitimate result.

Before we close, we would tender our greatest obligations to the English and German authors, from whom we have drawn abundantly in preparing this work; also to the Directors of the British Museum of London, and the Society of Antiquarians of Berlin, and especially to the authorities of the excavated City of Pompeii and its treasures in the Museum of Naples, where we were furnished with an intelligent guide and permitted to spend days in our researches. To each and all of these, who have so kindly promoted our labor, our heartfelt thanks are cordially returned.

Many of the engravings are from drawings made on the spot, but a greater number are from photographs, and executed with the greatest fidelity by German and French artists.

[iv]

Steel Plate Engravings.

| PAGE | |

| The Palace of the Cæsars, | 1 |

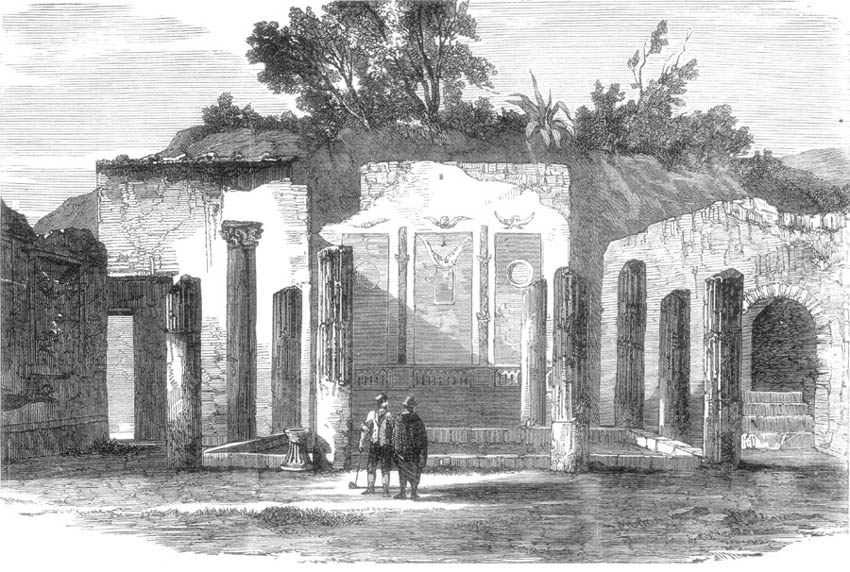

| House of the Tragic Poet—Sallust, | 112 |

| Egyptian Feast, | 270 |

| Approach to Karnac, | 384 |

| Temple of Karnac, | 470 |

| The Philae Islands, | 656 |

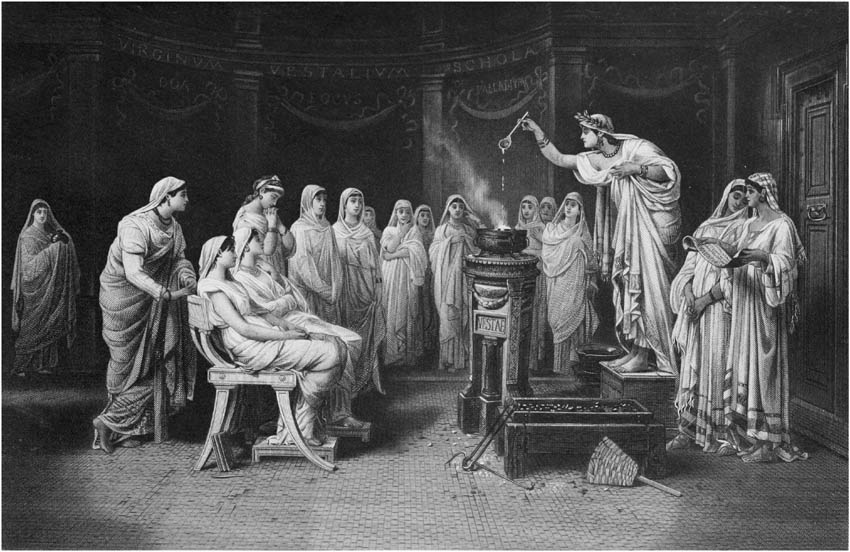

| School of the Vestal Virgins, | 832 |

[v]

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| Pompeii. | |

| The Glory of the City—Destruction—Excavation—Entering Pompeii (Page 21-25)—The Streets of the City—The Theatres of Pompeii—Villa of Julia Felix—Pavements and Sidewalks—Arrangement of Private Houses (Page 26-53)—Elegance of Domestic Architecture—Ground Plan of Roman House—Exterior Apartments—Interior Apartments—Dining Halls—The Triclinium—Materials and Construction—The Salve Lucru—Paintings and Decorations—The Drunken Hercules—Wall Decoration—The Peristyle—The House of Siricus—Political Inscriptions—Electioneering Advertisements—The Graffiti—Street of the Lupanar—Eighty Loaves of Bread Found—The House of the Balcony—Human Bodies Preserved—Discovered Bodies—House of Diomedes (Page 54-74)—Location of the Villa—Ground Plan of the Villa—Detail of Ground Plan—The Caldarium—Galleries and Halls—Porticoes and Terraces—Tomb and Family Sepulchre—The Villa Destroyed—Conclusive Evidence—Jewels and Ornaments—Pliny's Account of a Roman Garden—Stores and Eating Houses (Page 75-81)—Restaurant—Pompeian Bill of Fare—Circe, Daughter of the Sun—Houses of Pansa and Sallust (Page 82-102)—Curious Religious Painting—General View of House—Worship of the Lares—Domesticated Serpents—Discoveries Confirm Ancient Authors—Ornamentation and Draperies—Remarkable Mansions—House of the Vestals—Surgical and other Instruments—Shop of an Apothecary—House of Holconius (Page 103-112)—Decorations of the Bed-Chambers—Perseus and Andromeda—Epigraphs and Inscriptions—Ariadne Discovered by Bacchus—General Survey of the City (Page 113-118)—Wine Merchant's Sign—Sculptor's Laboratory— House of Emperor Joseph II | 17-119 |

| Amusements. | |

| The Amphitheatre—Coliseum—84,000 Seats—The Bloody Entertainments—Examining the Wounded—Theatres—Roman Baths (Page 147-156)—Description of the Baths—Cold Baths—Warm Chambers—The Vapor Baths—Hot-Air Baths—Social Games and Sports (Page 157-162)—Domestic Games—Jugglers—Game of Cities—Gymnastic Arts—Social Entertainments (Page 163-180)—Characteristics of the [vi] Dance—Grace and Dress of the Dancers—Position at the Table—Vases and Ornaments—Food and Vegetables—Mode of Eating—Reminders of Mortality—Egyptian Music and Entertainments (Page 181-188)—Musical Instruments—Jewish Music—Beer, Palm Wine, Etc—Games and Sports of the Egyptians (Page 189-202)—Games with Dice—Games of Ball—Wrestling—Intellectual Capabilities—Hunting | 120-202 |

| Domestic Life. | |

| Occupation of Women—Bathing—Wedding Ceremonies—Children's Toys—Writing Materials—Families, Schools and Marriages—Duties of Children—Dress, Toilet and Jewelry (Page 219-232)—The Chiton—Dress Materials—Styles of Wearing Hair—Head-Dress of Women—Hair-Pins—Sunshades—Crimes and Punishments; Contracts, Deeds, Etc. (Page 233-252)—Punishments—Laws Respecting Debt—Contracts—Superstition—Cure of Diseases—Houses, Villas, Farmyards, Orchards, Gardens, Etc. (Page 253-270)—Character of the People—Construction of Houses—Plans of Villas—Irrigation—Gardens—Egyptian Wealth (Page 271-280)—Gold and Silver—Worth of Gold—Treasures—Total Value of Gold | 203-280 |

| Domestic Utensils. | |

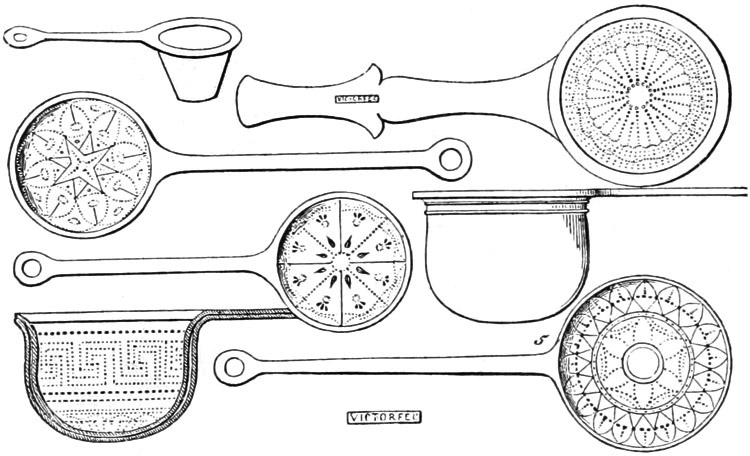

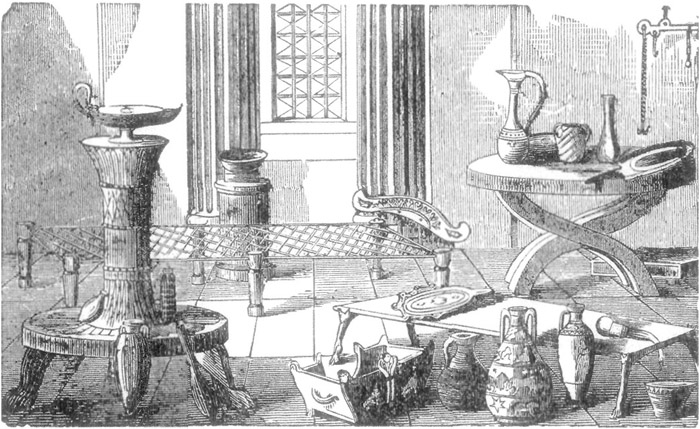

| Writing Materials—Literature—Curious Lamps—The Candelabrum—Candelabra—Oil-Lamps—The Steelyard—Drinking Vessels—Colored Glass—Glass—Glass Vessels—Articles of Jewelry—Toilet-Boxes, Etc.—Furniture (Page 309-322)—Chairs and Stools—Bed-Room Furniture—Tables, Etc.—Pottery—Drawings on Vases—Vases (Page 323-342)—Greek Vases—Inscriptions on Vases—Historical Subjects on Vases—Uses of Vases—Vases Found in Tombs—Silver Vessels—Decorated Vases | 281-342 |

| Employment. | |

| Colored Glass Vessels—Imitation Jewels—Potters—Carpenter's Tools—Professions—Husbandry—Rise of the Nile—Agricultural Implements—Agriculture—Baking, Dyeing and Painting (Page 363-384)—Flour Mills—Bread-Baking—Dyeing—Scouring and Dyeing—Coloring Substances—Mineral Used for Dyeing—Cost of Dyeing—Cloth Manufacture—Persian Costumes | 343-384 |

| Troy. | |

| Ruins at Hissarlik—Settlement of Troy—First Settlers—Scæan Gate—Call of Menelaus—Houses at Troy—Objects Found in Houses—Silver Vases—Taking out the Treasure—Shield of the Treasure—Contents of the Treasure—Ear-Rings and Chains—Gold Buttons, Studs, Etc.—Silver Goblet and Vases—Weapons of Troy—Terra Cotta Mugs—Condition of the Roads—Lack of Inscriptions | 385-422 |

| Nineveh and Babylon.[vii] | |

| Explorations of Niebuhr and Rich—Excavations at Kouyunjik Palace—Sennacherib's Conquests—Highly-Finished Sculptures—North Palace, Kouyunjik—Temple of Solomon—The Oracle—Description of the Palace—Modern Houses of Persia—Chambers in the Palace—The Walls—Grandeur of Babylon—Building Materials—History of Babylon—Karnac and Baalbec (Page 461-473)—Stupendous Remains—Temple of Luxor—Chambers of the Great Pyramid—The Great Temple—The Pantheon at Rome—Egyptian Obelisks—Obelisks | 423-484 |

| Religion or Mythology. | |

| Mythology—Mythological Characters—The Pythian Apollo—Phœbus Apollo—Niobe and Leto—Daphne—Kyrene—Hermes—The Sorrow of Demeter—The Sleep of Endymion—Phaethon—Briareos—Dionysos—Pentheus—Asklepios—Ixion—Tantalos—The Toils of Herakles—Admetos—Epimetheus and Pandora—Io and Prometheus—Deukalion—Poseidon and Athene—Medusa—Danae—Perseus—Andromeda—Akrisios—Kephalos and Prokris—Skylla—Phrixos and Helle—Medeia—Theseus—Ariadne—Arethusa—Tyro—Narkissos—Orpheus and Eurydike—Kadmos and Europa—Bellerophon—Althaia and the Burning Brand—Iamos | 485-642 |

| Fine Arts. | |

| Egyptian Sculpture—Etruscan Painting—Renowned Painters—Parrhasius—Colors Used—Sculpture Painting—Fresco Painting—Sculpturing (Page 667-694)—Sculpture in Greece and Egypt—Sculptures of Ancient Kings—Animal Sculpture—Modeling of the Human Figure—"The Sculptor of the Gods"—Grandeur of Style—Statues—Description of Statues—Work of Lysippus—The Macedonian Age—Roman Art—Copies of Ancient Gods—Mosaic (Page 695-702)—Mosaic Subjects—Battle Represented in Mosaics—Grandeur of Style | 643-702 |

| Literature. | |

| Homer—Paris—Achilles—The Vengeance of Odysseus—Sophocles—Herodotus—The Crocodile—Artabanus Dissuades Xerxes—Socrates—Socrates and Aristodemus—Aristophanes—Plato—The Perfect Beauty—Last Hours of Socrates—Demosthenes—Philip and the Athenians—Measures to Resist Philip—Former Athenians Described—Oration on the Crown—Invective against Catiline—Expulsion of Catiline from Rome—The Tyrant Prætor Denounced—Immortality of the Soul—Julius Cæsar—The Germans—Battle of Pharsalia—Virgil—Employment of the Bee—Punishments in Hell—Horace—To Licinius—Happiness Founded on Wisdom—The Equality of Man—Plutarch—Proscription of Sylla—Demosthenes and Cicero Compared | 703-832 |

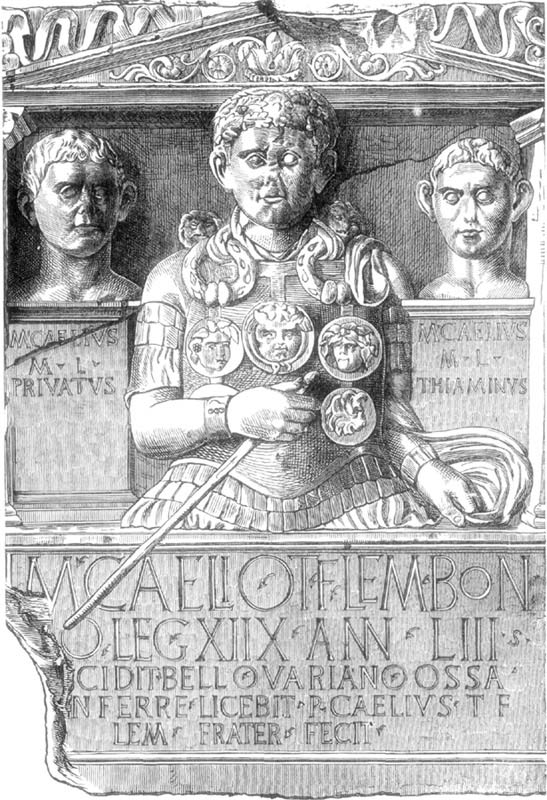

| Tombs and Catacombs.[viii] | |

| Extent of the Tombs—An Acre and a quarter in a Tomb—Sculpturings—Painting—Burying According to Rank—Mummies—Mummy Cases and Sarcophagi—Roman Tombs—Inscriptions—The Catacombs (Page 873-910)—Inscriptions—Catacombs—Christian Inscriptions—Early Inscriptions—Catacombs, nearly 900 miles long—Utensils from the Catacombs—Paintings—S. Calixtus—Lord's Supper | 833-910 |

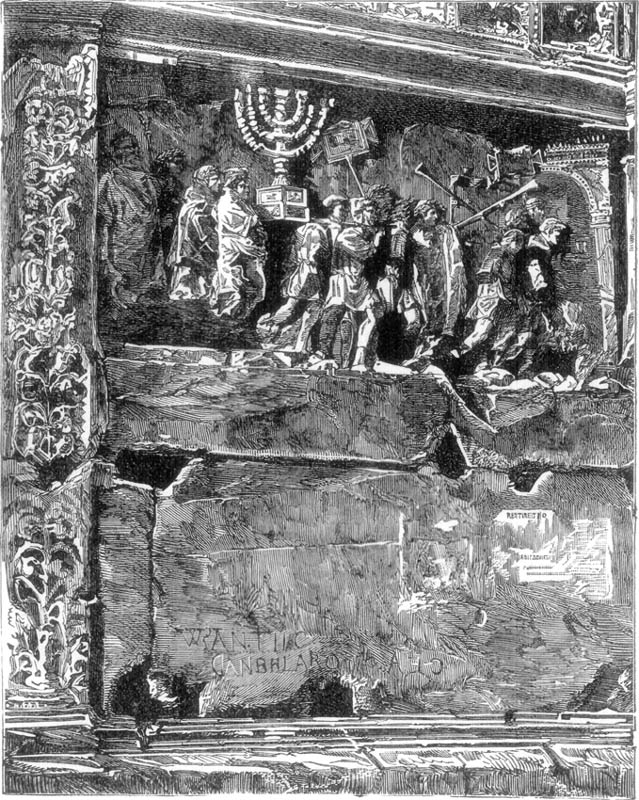

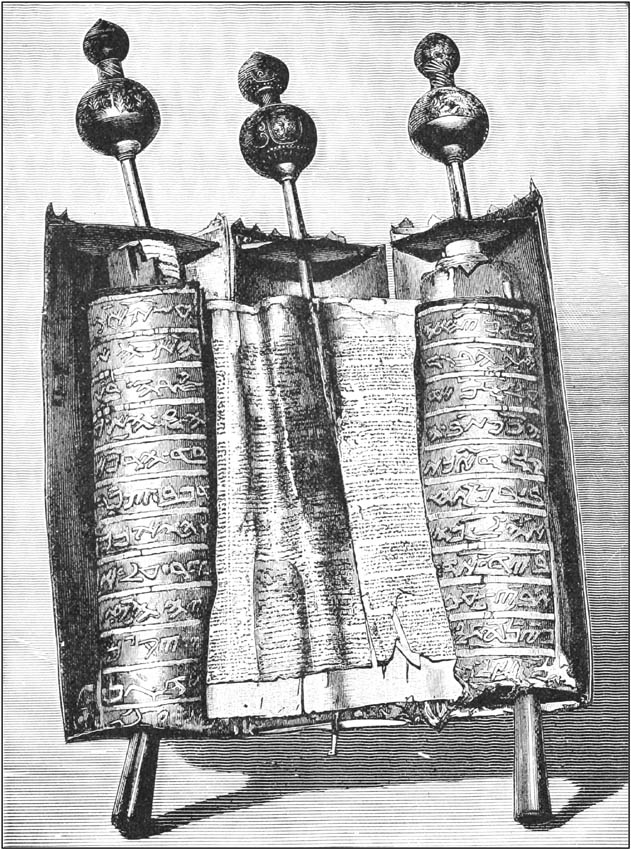

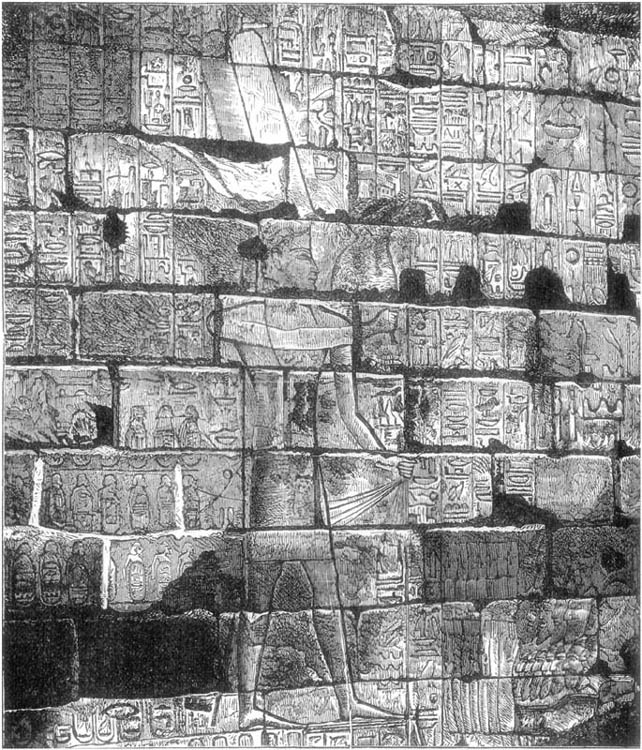

| Truth of the Bible. | |

| The Assyrian and Babylonian Discoveries—1100 Christian Inscriptions—The use of the Bible for Excavators—Accordance with Ancient Writings—Frieze from the Arch of Titus—No Book produced by Chance—God the Author—Its Great Antiquity—The Pentateuch—Preservation of the Scripture—Its Important Discoveries—Its Peculiar Style—Its Harmony—Its Impartiality—Its Prophecies—Its Important Doctrines—Its Holy Tendency—Its Aims—Its Effects—Its General Reception—Persecuted but not Persecuting | 911-944 |

[ix]

ILLUSTRATIONS

BY GERMAN ARTISTS.

| Destruction of Pompeii | 17 |

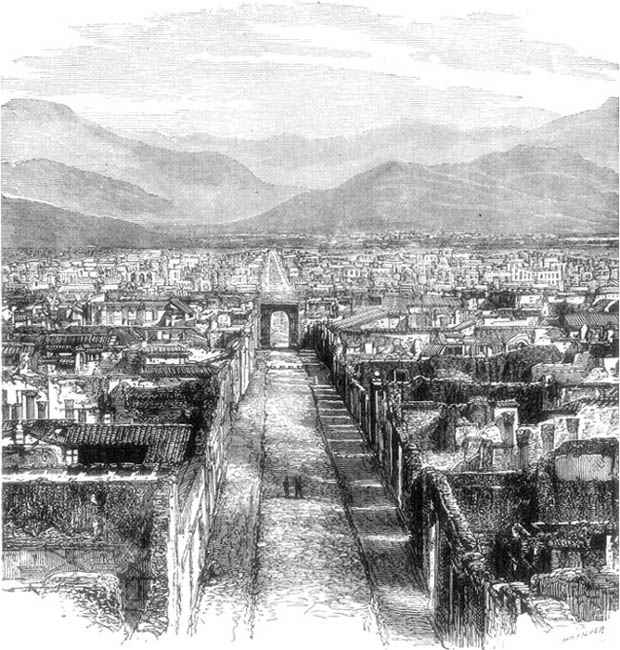

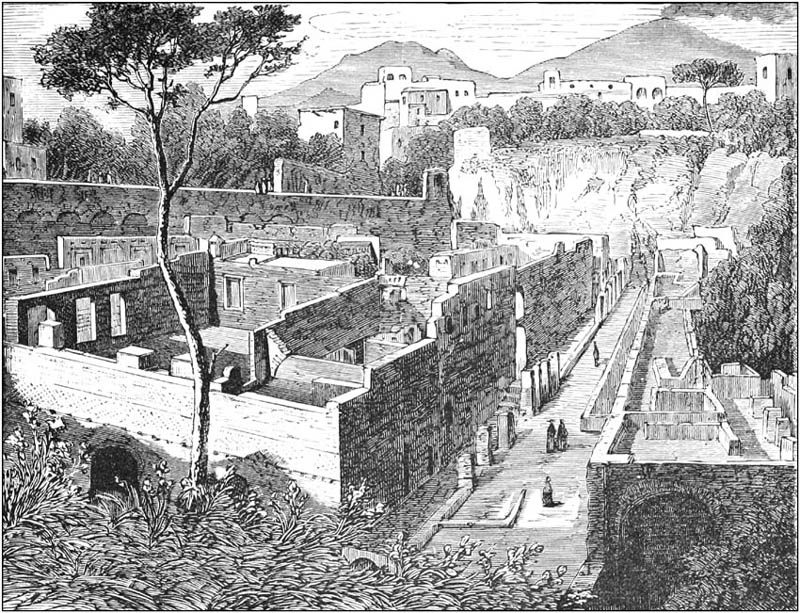

| View of Pompeii. (From a Photograph) | 23 |

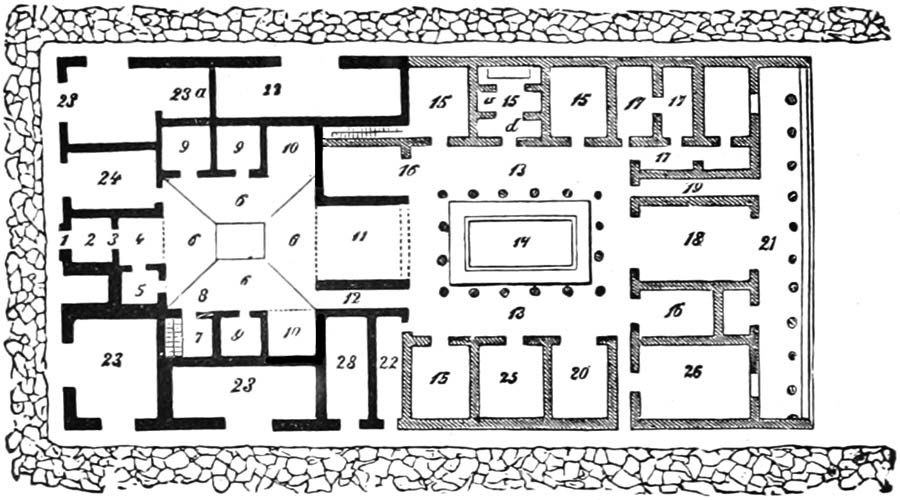

| Plan of a Roman House | 28 |

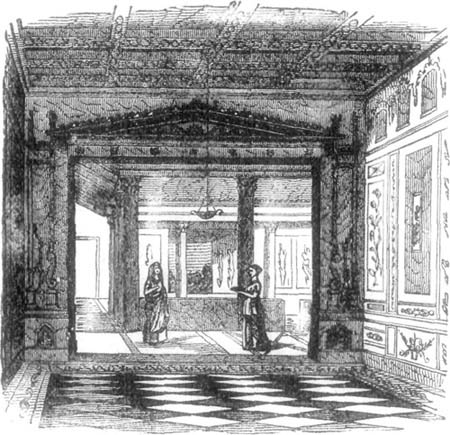

| Vestibule of a Pompeian House | 30 |

| Triclinium or Dining-room | 33 |

| Hercules Drunk. (From Pompeii) | 37 |

| Discovered Body at Pompeii | 51 |

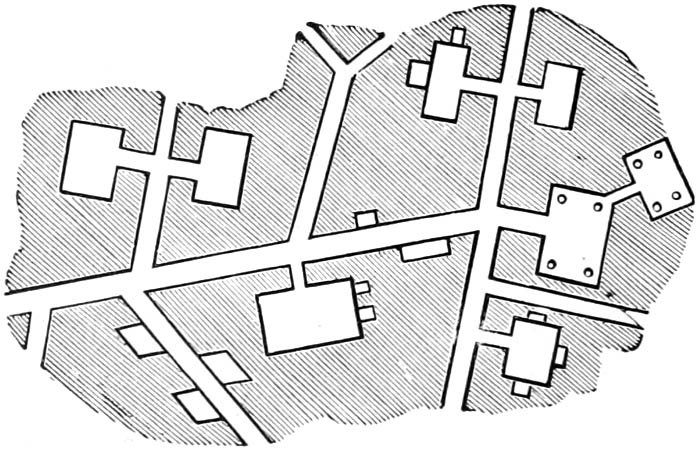

| Ground Plan of the Suburban Villa of Diomedes | 57 |

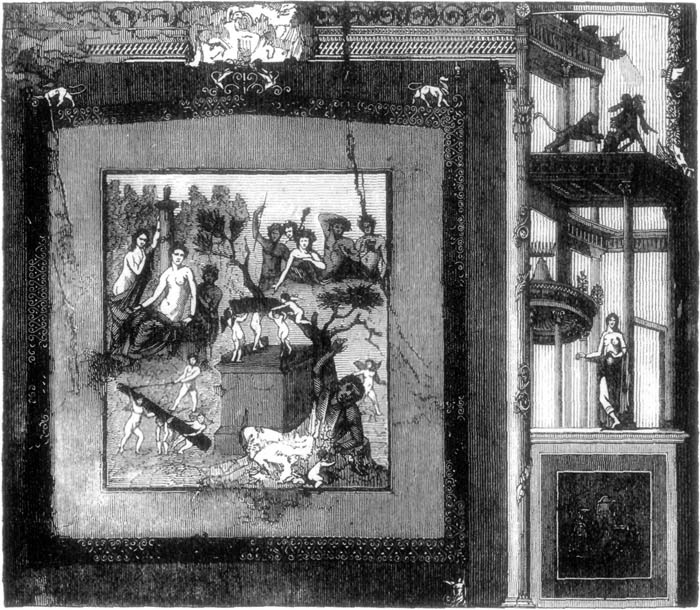

| Wall Painting at Pompeii | 69 |

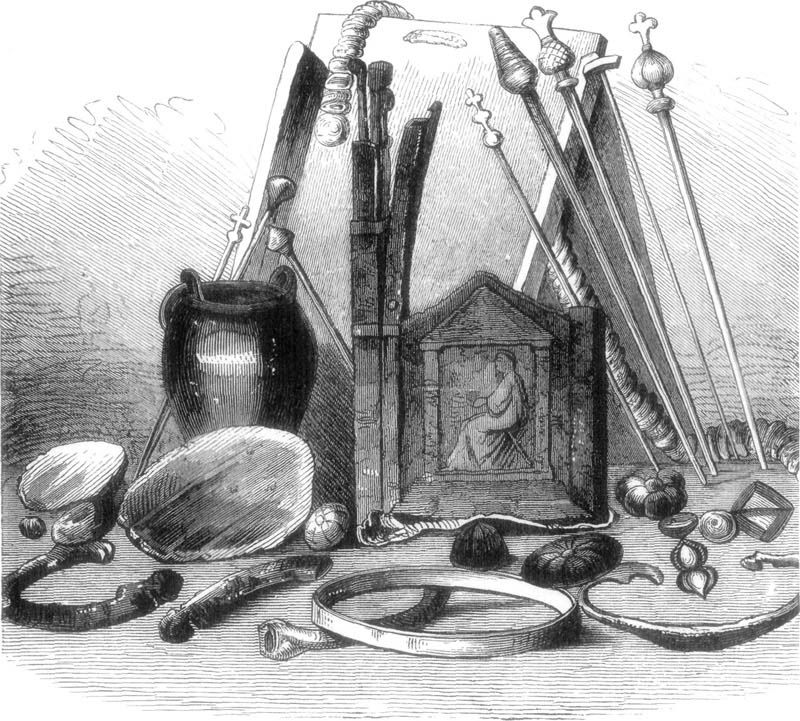

| Household Utensils | 72 |

| Restaurant. (From Wall Painting) | 77 |

| Bed and Table at Pompeii. (From Wall Painting) | 78 |

| Plan of a Triclinium | 79 |

| Head of Circe | 81 |

| Kitchen Furniture at Pompeii | 84 |

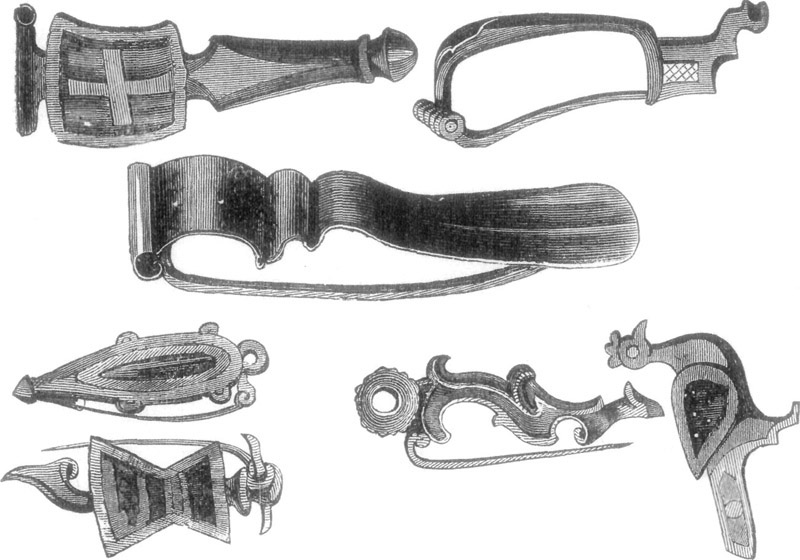

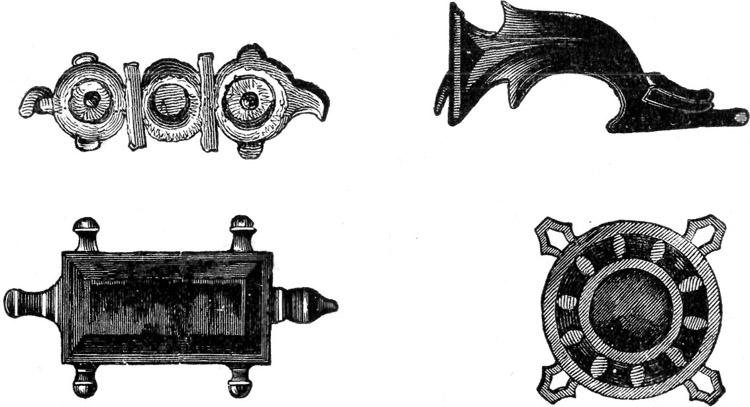

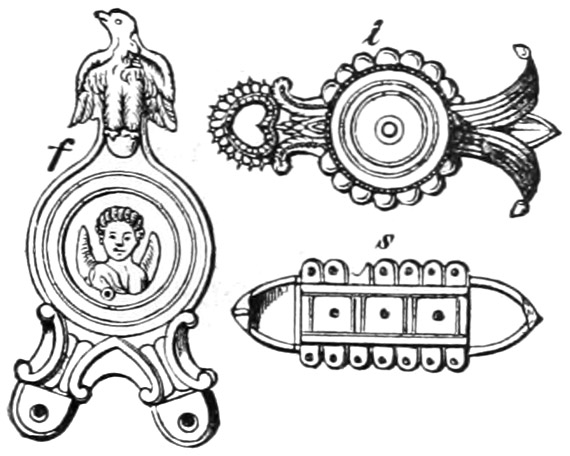

| Brooches of Gold found at Pompeii | 98 |

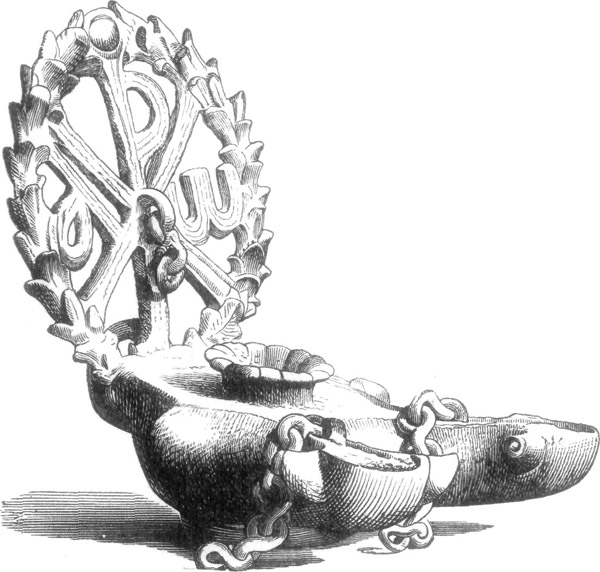

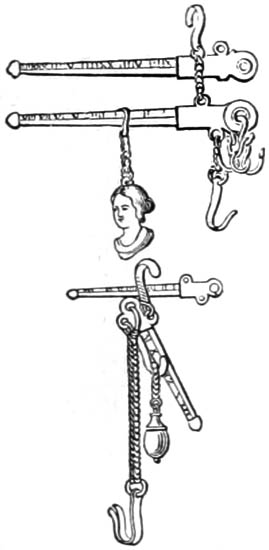

| Scales found at Pompeii | 100 |

| Wall Painting found at Pompeii | 105 |

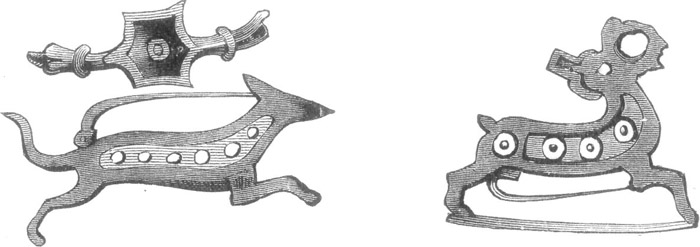

| Gold Breastpins found at Pompeii | 114 |

| A Laboratory, as found in Pompeii | 117 |

| First Walls Discovered in Pompeii | 118 |

| View of the Amphitheatre at Pompeii | 121[x] |

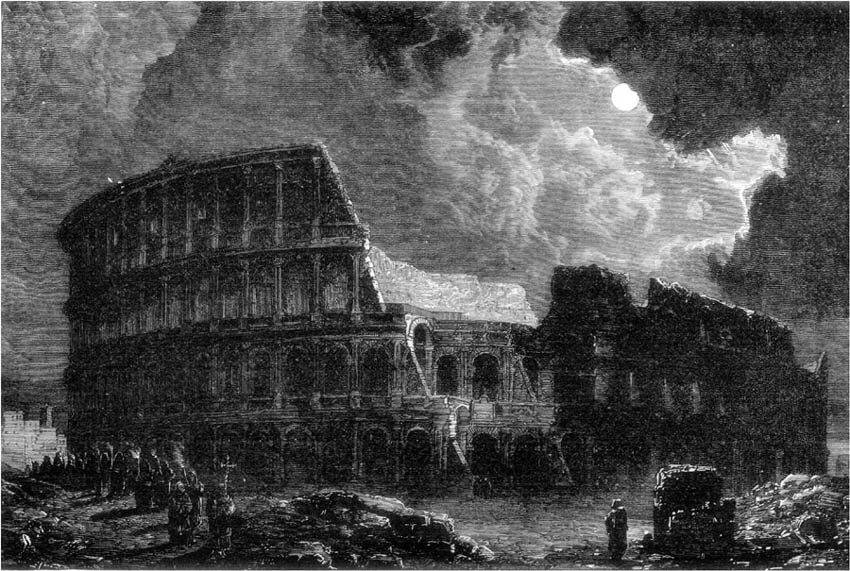

| Coliseum of Rome | 128 |

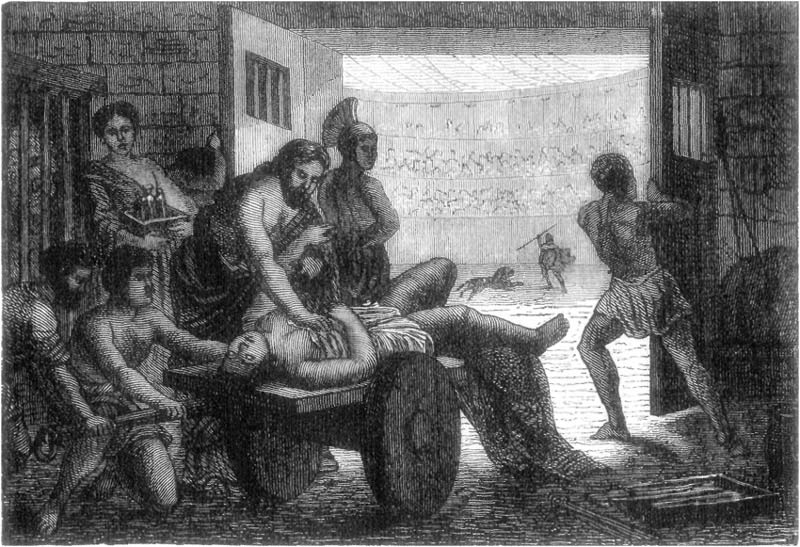

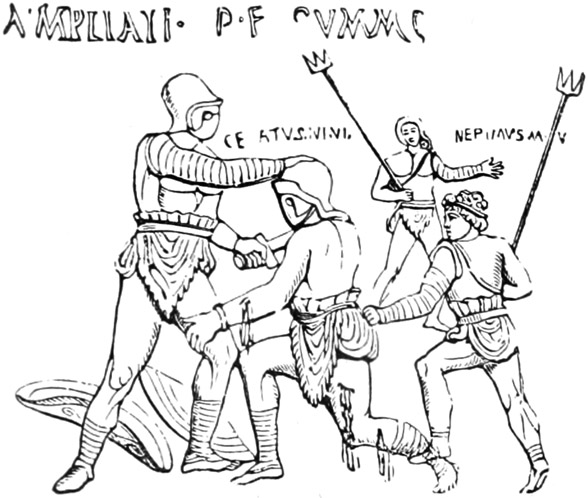

| Examining the Wounded | 133 |

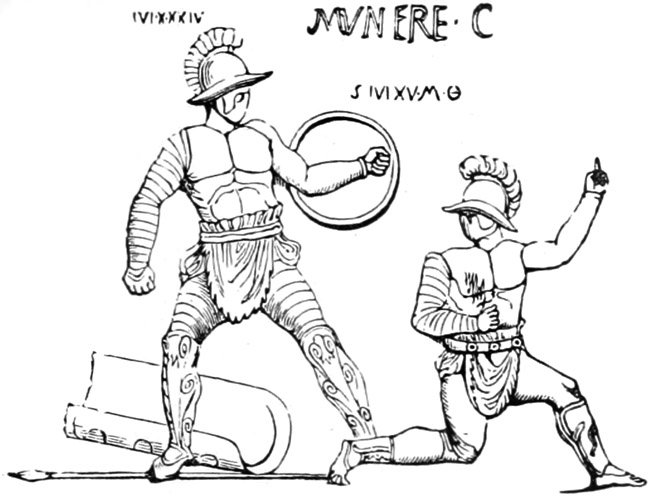

| Asking Pardon | 135 |

| Not Granted | 135 |

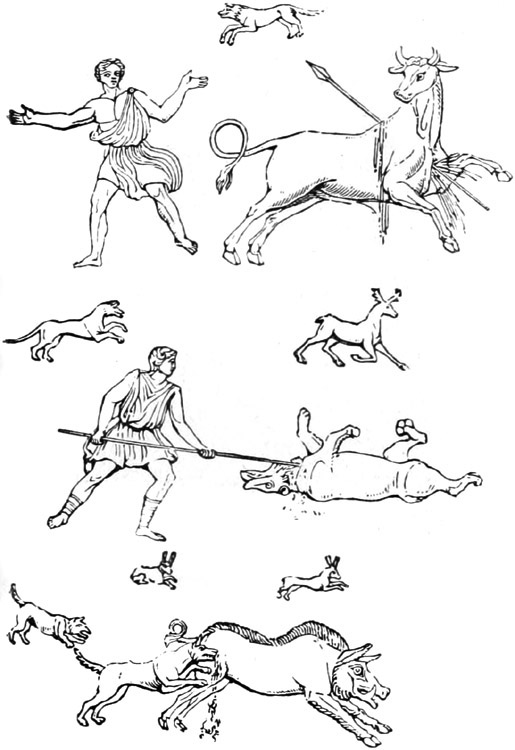

| Combats with Beasts | 137 |

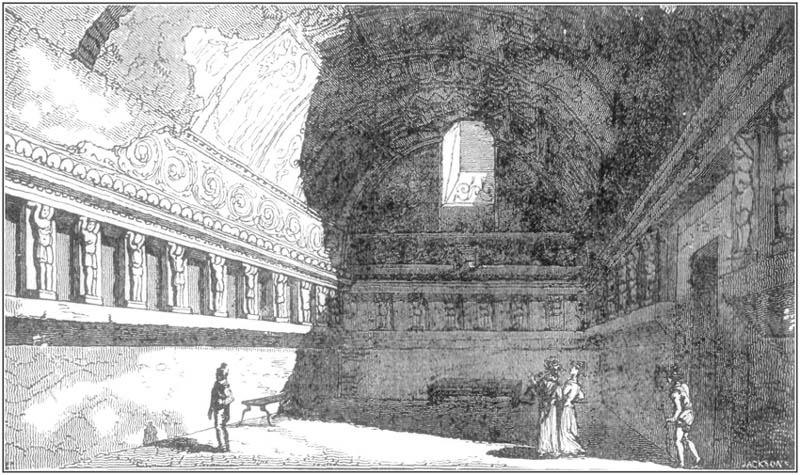

| View of the Tepidarium | 151 |

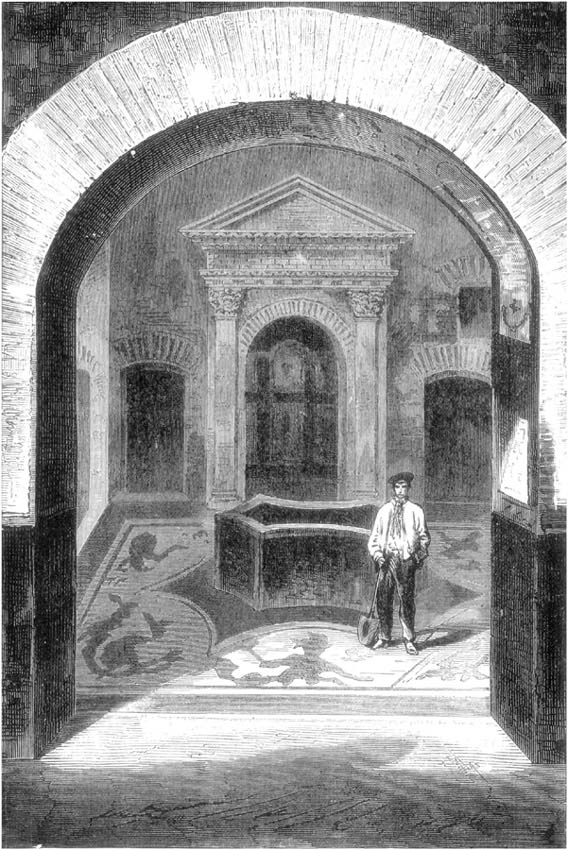

| Ancient Bath Room. (As Discovered) | 155 |

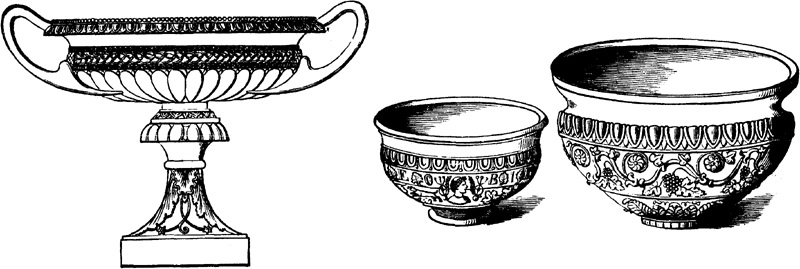

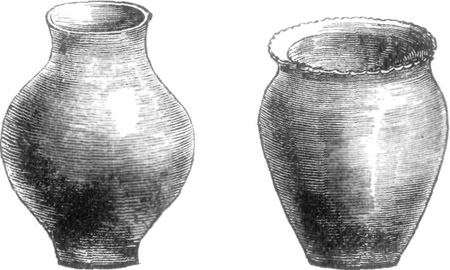

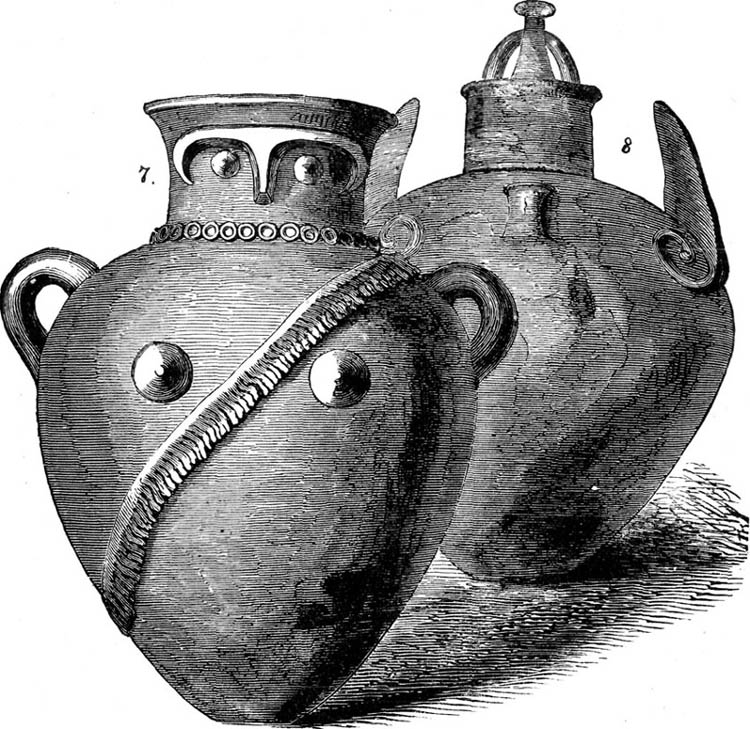

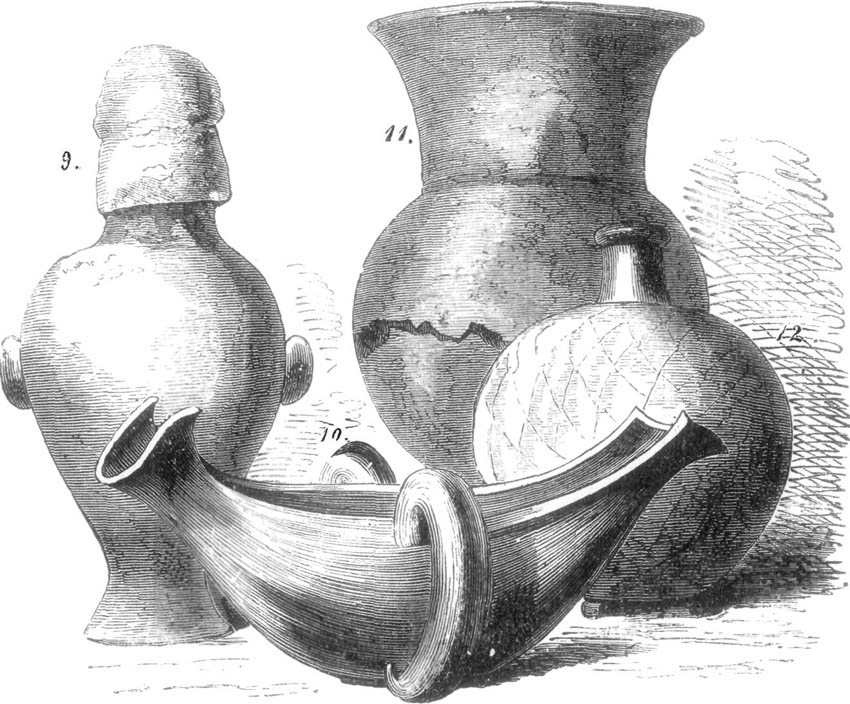

| Egyptian Vases | 173 |

| Social Enjoyment of Women. (From an Ancient Painting) | 205 |

| Gold Pins | 220 |

| Shawl or Toga Pin | 220 |

| Pearl Set Pins | 221 |

| Stone Set Brooches | 224 |

| Hair Dress. (From Pompeii) | 227 |

| Toilet Articles found at Pompeii | 231 |

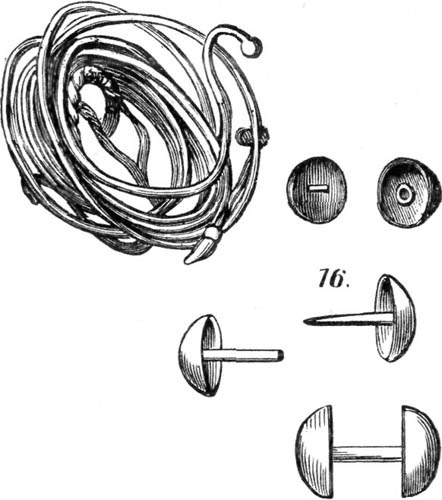

| Wreath of Oak. (Life Saving) | 247 |

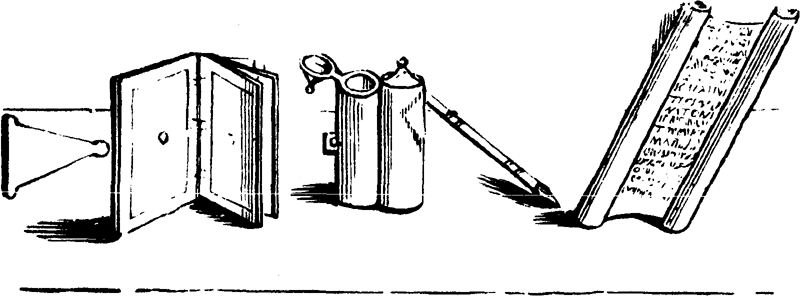

| Tabulæ, Calamus, and Papyrus | 283 |

| Tabulæ, Stylus, and Papyrus | 283 |

| Tabulæ and Ink Stand | 284 |

| Libraries and Money | 284 |

| Gold Lamp. (Found at Pompeii) | 287 |

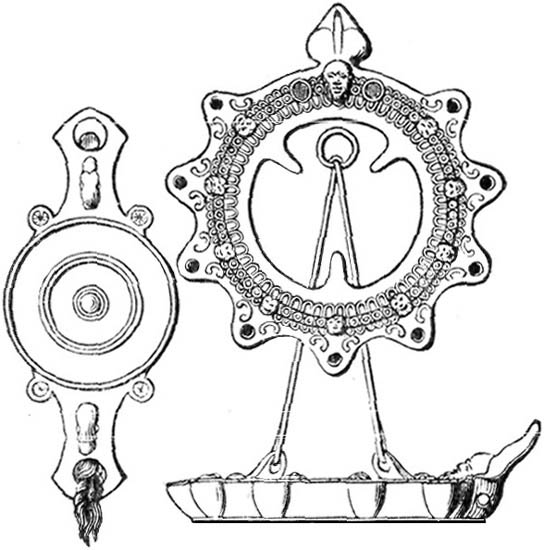

| Candelabrum, or Lamp Stand | 289 |

| Candelabra, or Lamp Stands | 290 |

| Standing Lamp | 293 |

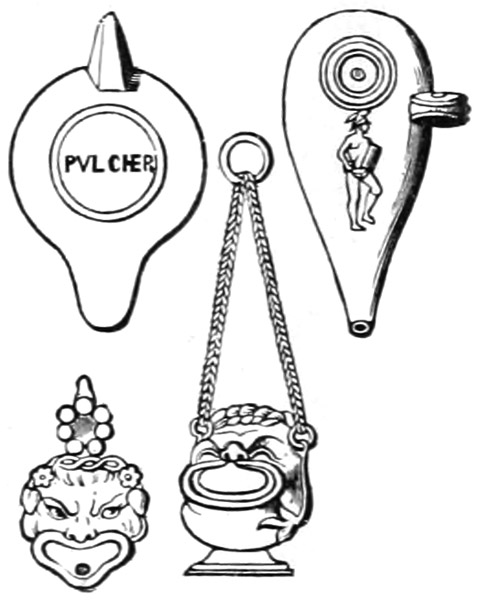

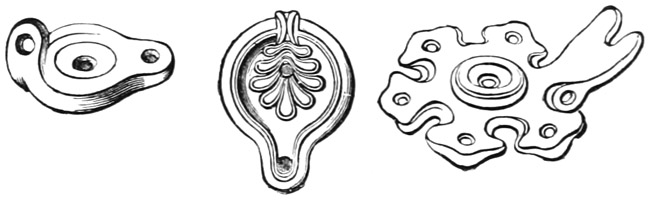

| Ancient Lamps | 293 |

| Scales and Weights | 295 |

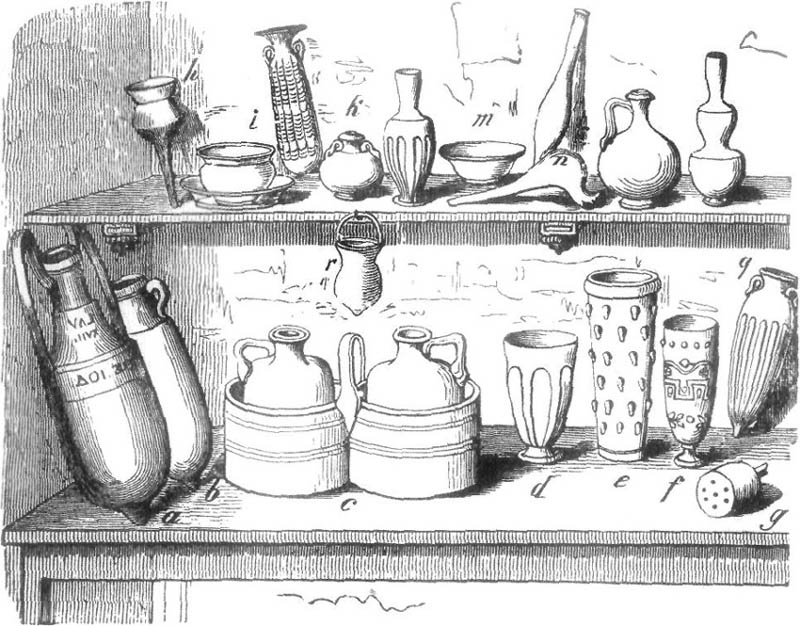

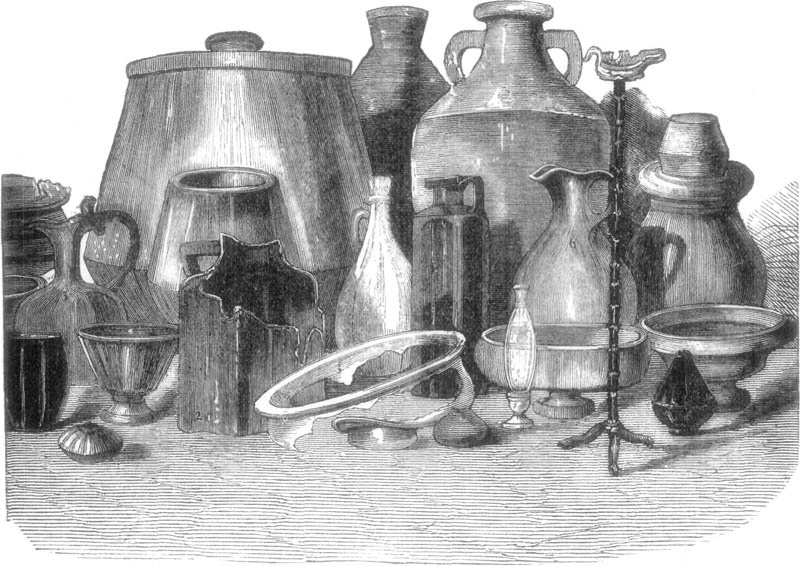

| Vessels. (From Pompeii) | 296 |

| Drinking Vessel | 297 |

| Glass Vessels. (From Pompeii) | 302 |

| Cups and Metals | 304 |

| Gold Jewelry. (From Pompeii) | 305 |

| Heavy Gold Pins | 306 |

| Brooches Inset with Stone | 307 |

| Safety Toga Pins | 308[xi] |

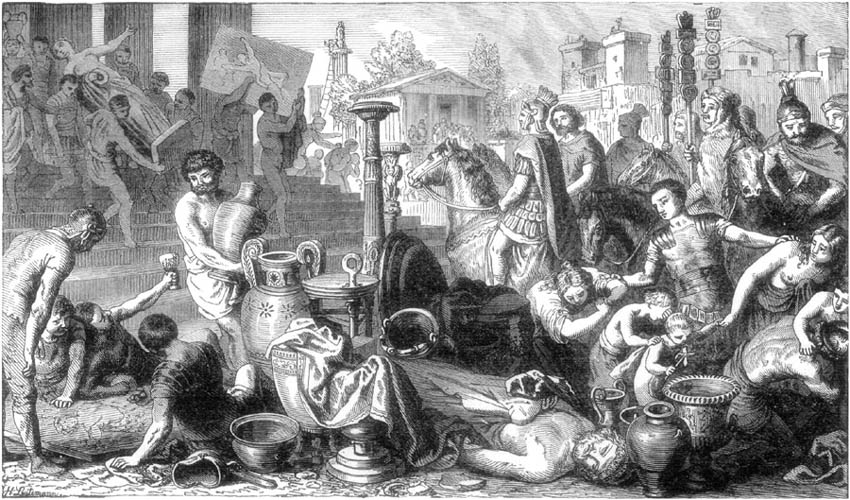

| Plundering Corinth | 317 |

| Greek Vase | 321 |

| Etruscan Vase | 324 |

| Roman Vases | 325 |

| Vase Representing a Marriage. (Found at Pompeii) | 328 |

| Vase Representing Trojan War. (Found at Pompeii) | 333 |

| Vase. (Found at Pompeii) | 334 |

| Vase Representing Greek Sacrifice | 336 |

| Vase 2,000 Years Old | 337 |

| Silver Platter | 339 |

| Silver Cup. (Found at Hildesheim) | 340 |

| Vase of the First Century | 341 |

| Dish of the First Century | 341 |

| Ancient Glass Vessels | 346 |

| Glass Brooch | 347 |

| Imitation of Real Stone | 348 |

| Ancient Egyptian Pottery | 350 |

| Mill and Bakery at Pompeii | 365 |

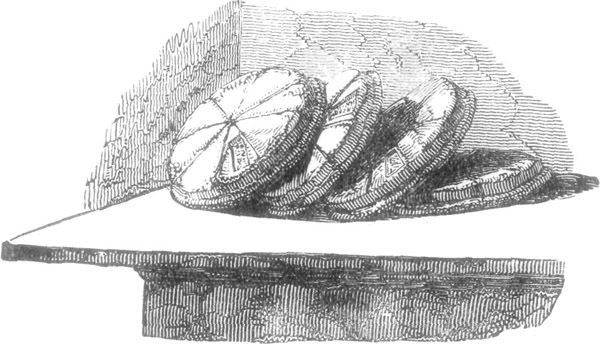

| Bread Discovered in Pompeii | 371 |

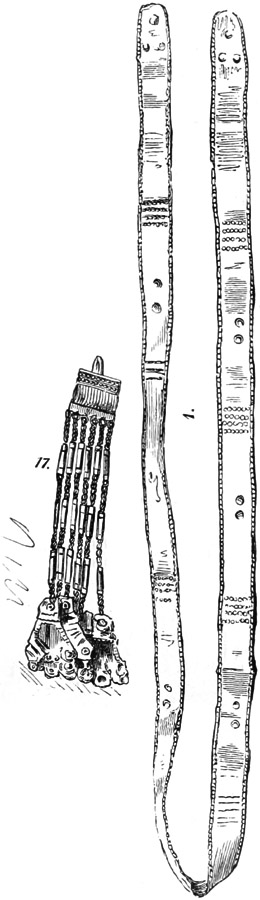

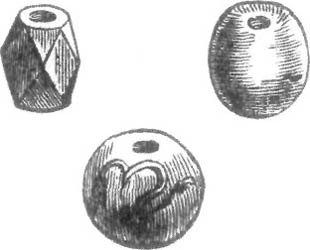

| Metals and Beads | 389 |

| Terra-cotta Lamps | 394 |

| Bronze Lamps | 394 |

| Golden Cups of Priam. (Found at Troy) | 396 |

| Wonderful Vases of Terra-cotta from Palace of Priam | 399 |

| From Palace of Priam | 400 |

| Lids and Metals of Priam | 401 |

| Treasures of Priam. (Found at Troy) | 404 |

| Part of Machine of Priam | 406 |

| Jewelry of Gold and Stones | 406 |

| Vessel Found in the Palace of Priam | 407 |

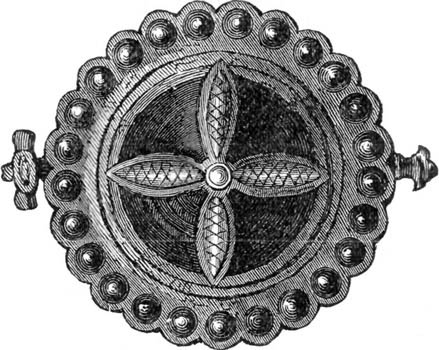

| Shield of the Palace of Priam | 408 |

| Gold Necklace of Troy | 409[xii] |

| Gold Tassels of Troy | 409 |

| Lamps found at Troy | 409 |

| Studs and Bracelets of Priam | 411 |

| Gold Pins with Set Gems | 411 |

| Gold Ear-rings of Troy | 412 |

| Spears, Lances, Ax and Chain | 415 |

| Shears, Knives and Spears | 415 |

| Lances Found at Palace of Priam, Troy | 416 |

| Coins or Metals | 418 |

| Elegant Brooch of Troy | 421 |

| Lamp found at Troy | 422 |

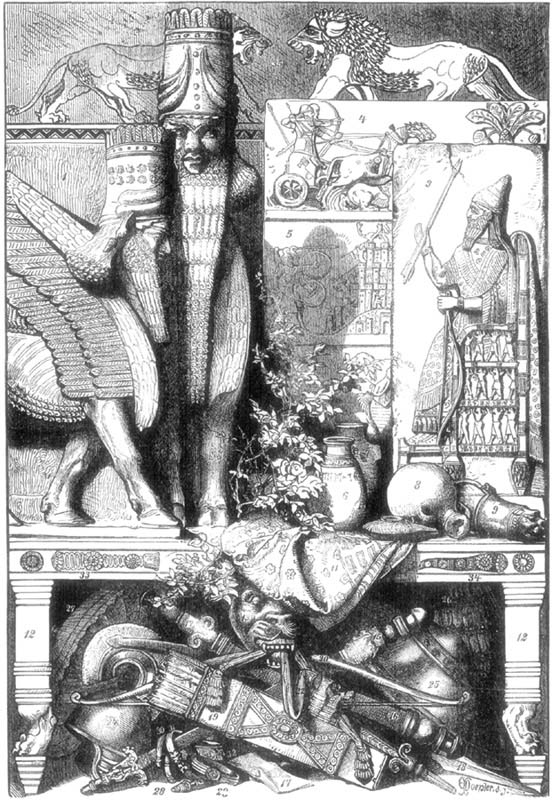

| Palace of Sennacherib | 427 |

| Discovered in the Palace | 435 |

| View of a Hall | 445 |

| Columns of Karnac | 463 |

| The Great Pyramids and Sphinx | 469 |

| Ruins of Baalbec | 473 |

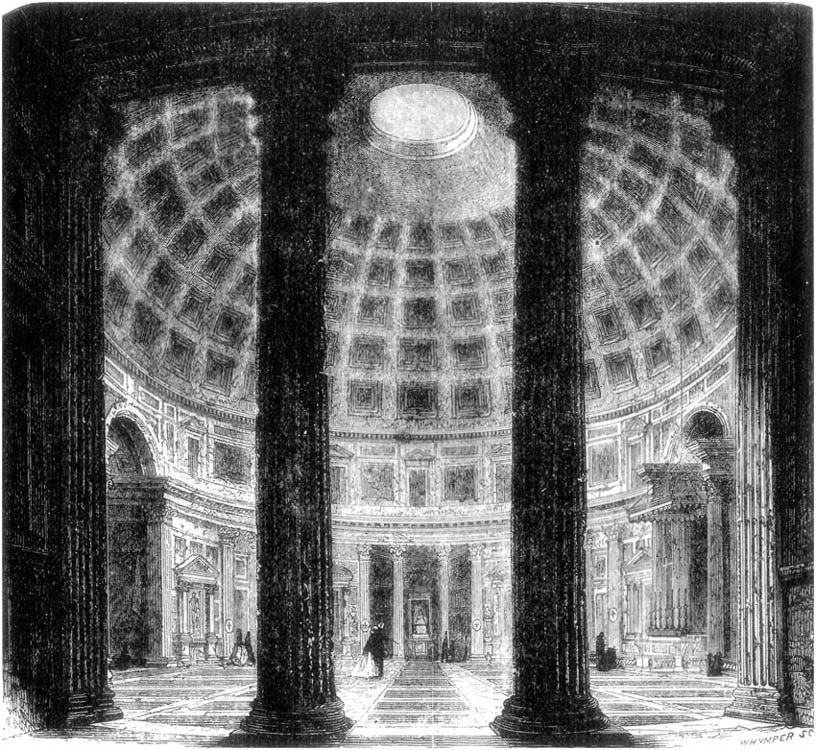

| View of the Pantheon at Rome | 475 |

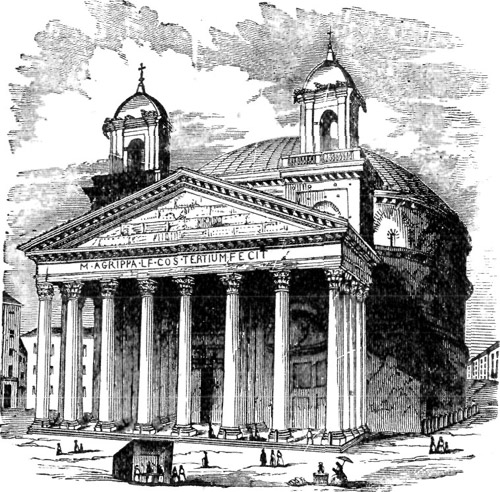

| Pantheon at Rome | 477 |

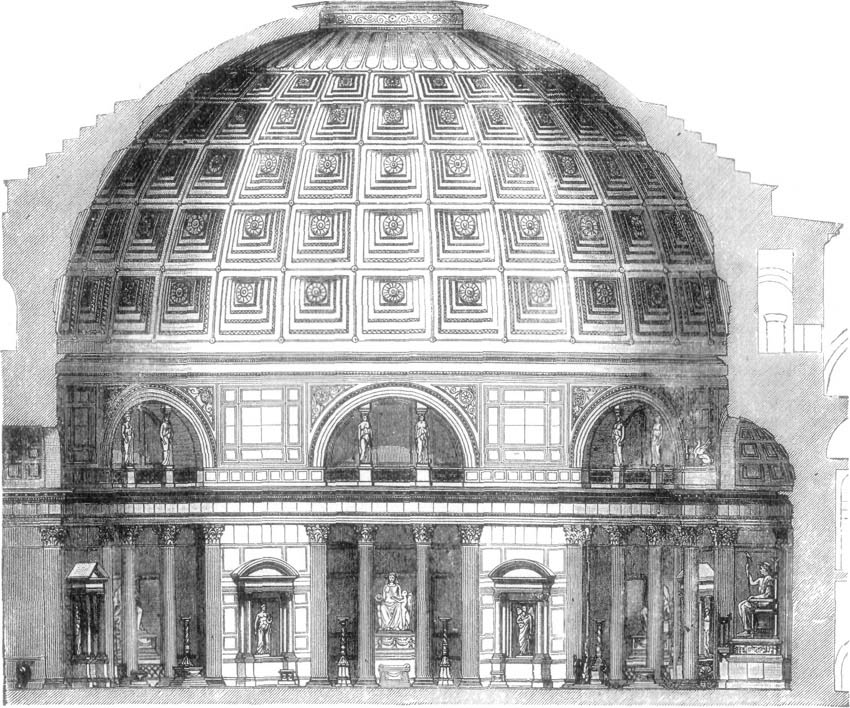

| Half Section of the Pantheon | 478 |

| Obelisk of Heliopolis | 481 |

| Jupiter. (or Zeus) | 491 |

| Apollo. (From an Ancient Sculpture) | 495 |

| Pluto and His Wife | 503 |

| Ceres. (or Demeter. From Pompeii Wall Painting) | 512 |

| Juno. (or Here) | 516 |

| Diana. (or Artemis) | 520 |

| Vulcan. (or Hephaistos) | 526 |

| Minerva. (or Pallas Athene. Found at Pompeii) | 530 |

| Ancient Sculpturing on Tantalos | 537 |

| Urania. (Muse of Astronomy) | 538 |

| Jupiter. (or Zeus with his Thunderbolt) | 544[xiii] |

| Thalia, the Muse | 550 |

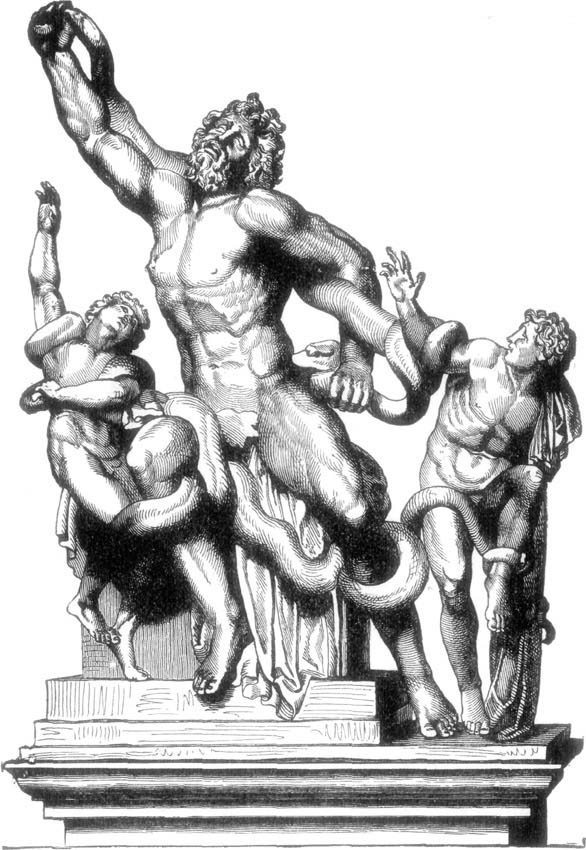

| Laocoon, the False Priest | 555 |

| Grecian Altar. (3000 years old) | 563 |

| Themis. (Goddess of Law) | 565 |

| Euterpe. (Muse of Pleasure) | 577 |

| Thalia. (Muse of Comedy) | 584 |

| Numa Pompilius Visiting the Nymph Egeria | 591 |

| Polyhymnia. (Muse of Rhetoric) | 603 |

| Sphinx of Egypt | 607 |

| Calliope. (Muse of Heroic Verse) | 614 |

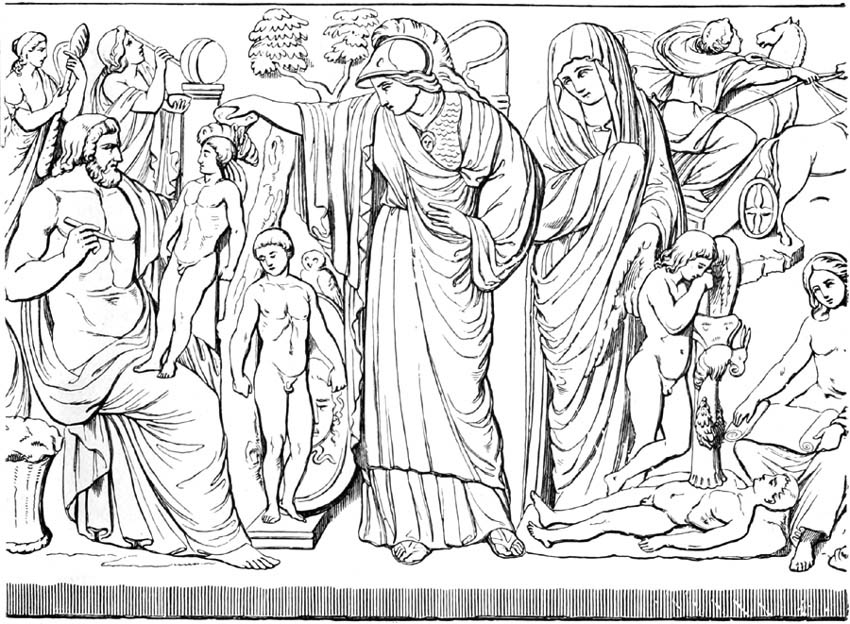

| The Origin of Man | 617 |

| Erate. (Muse of the Lute) | 623 |

| Terpsichore. (Muse of Dancing) | 625 |

| Ancient Sacrifice. (From Wall Painting of Pompeii) | 631 |

| Melpomene. (Muse of Tragedy) | 639 |

| Clio. (Muse of History) | 642 |

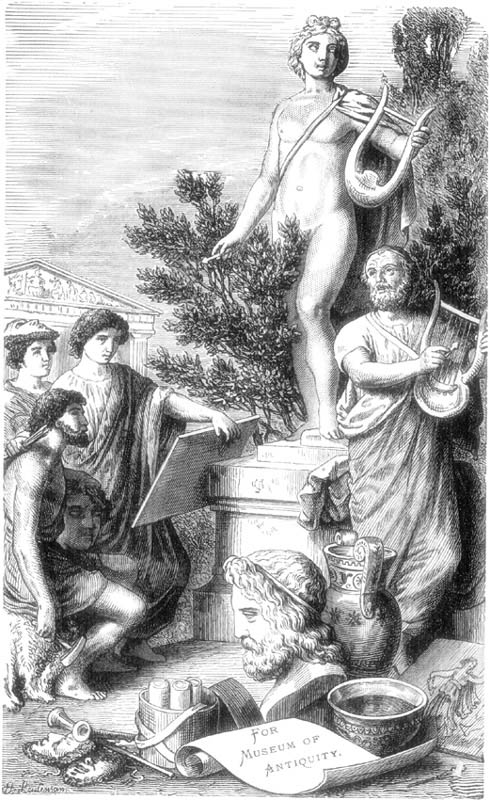

| Ancient Art and Literature | 645 |

| Painting. (2600 years old) | 655 |

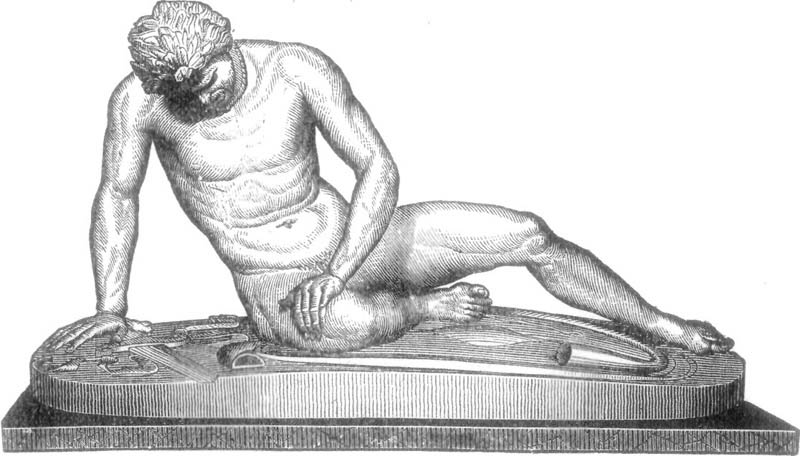

| Dying Gladiator | 689 |

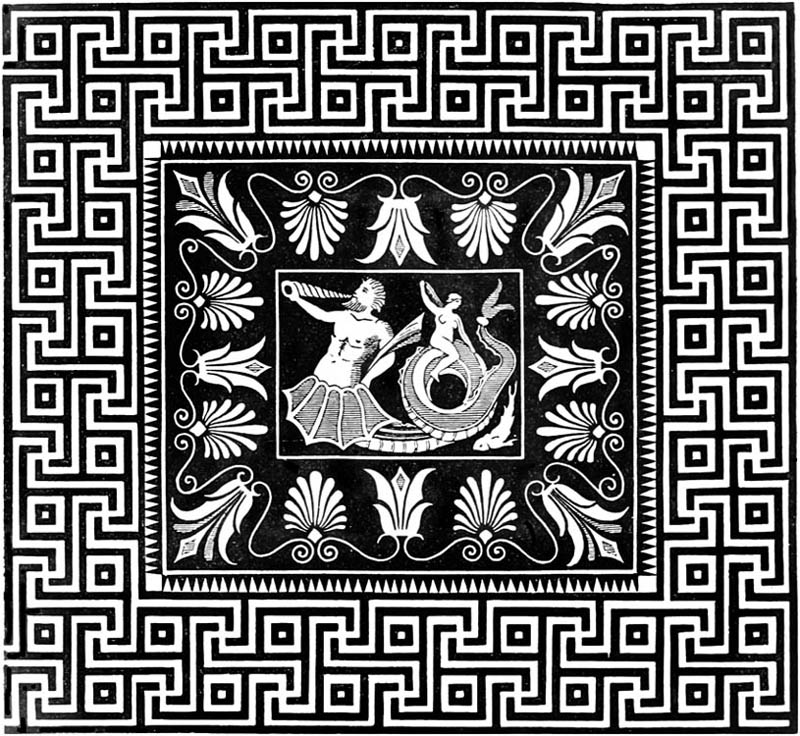

| Mosaic Floor | 696 |

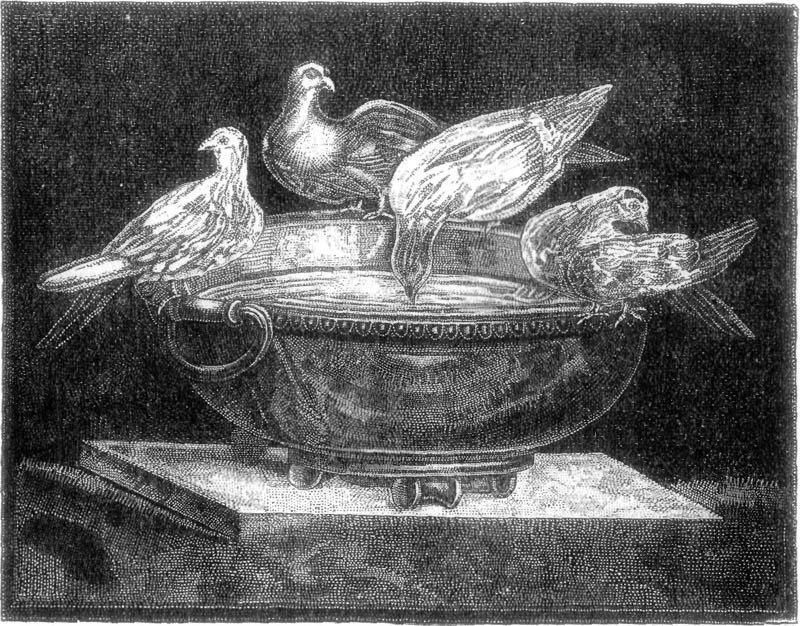

| Mosaic Doves | 697 |

| Apollo Charming Nature | 701 |

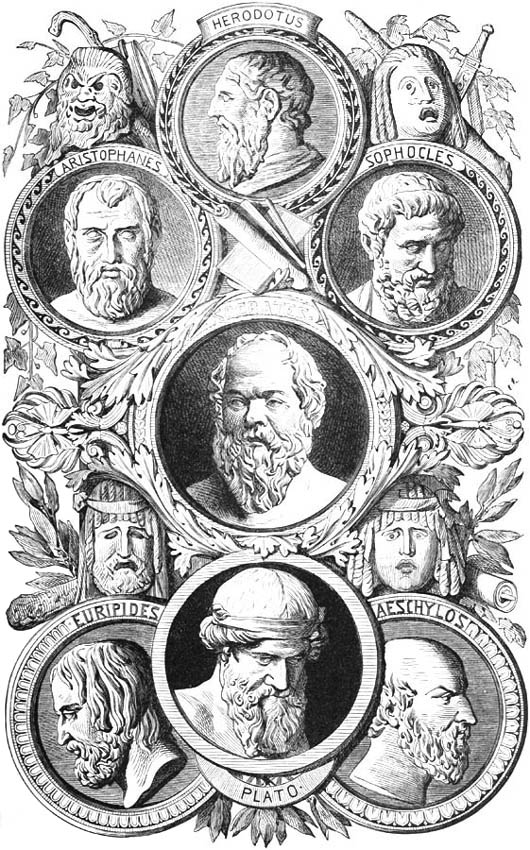

| Ancient Authors | 709 |

| Library of Herculaneum | 723 |

| Trojan Heroes | 735 |

| Ancient Metal Engraving | 745 |

| Socrates Drinking the Poison | 762 |

| From Ancient Sculpturing | 775 |

| King Philip. (of Macedon) | 784 |

| Augustus Cæsar. (Found at Pompeii) | 795 |

| Julius Cæsar. (From an Ancient Sculpturing) | 805 |

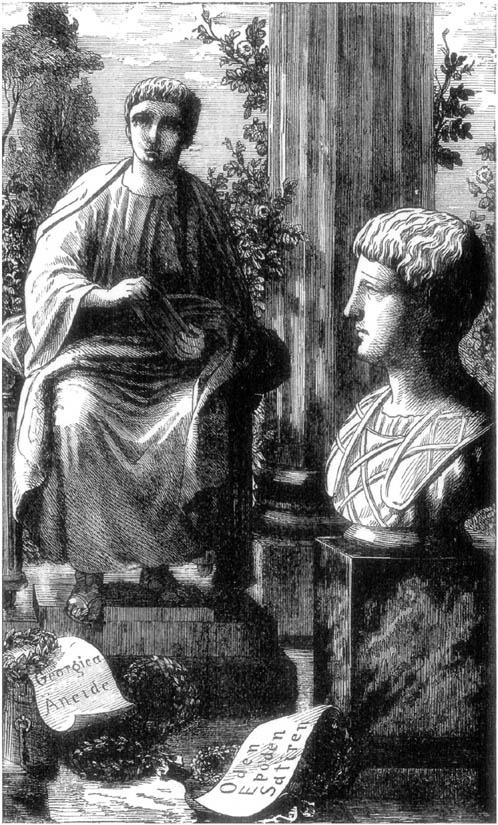

| Virgil and Horace | 813 |

| Euclid | 824[xiv] |

| Alexander Severus | 831 |

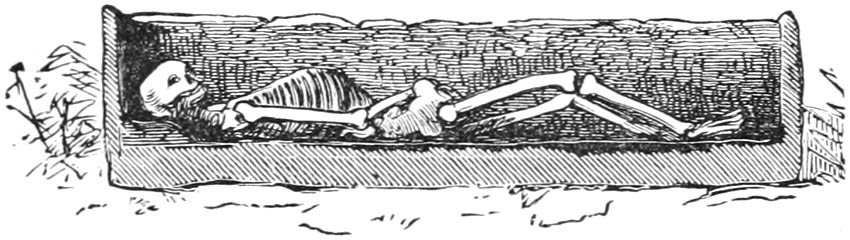

| Egyptian Tomb | 835 |

| Sarcophagus, or Coffin. (With Noah's Ark Cut in Relief on the Outside) | 841 |

| Coffin of Alabaster. (Features of the Deceased Sculptured) | 843 |

| Discovered Tomb with its Treasures. (At Pompeii) | 847 |

| Articles Found in a Tomb | 852 |

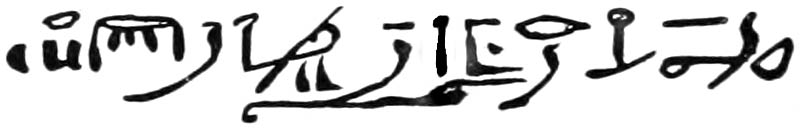

| Hieroglyphics | 857, 858, 859 |

| Egyptian Pillar | 862 |

| Egyptian Column | 867 |

| Sections of the Catacombs with Chambers | 874 |

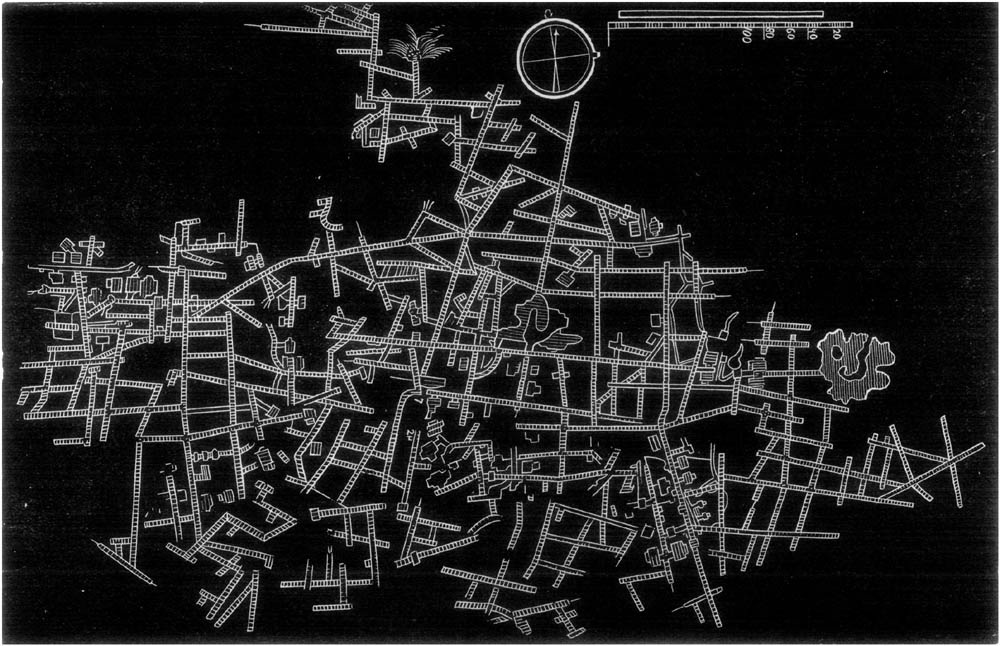

| Plan of the Catacombs at Rome | 875 |

| Stone Coffin | 878 |

| Stone Coffin with Open Side | 879 |

| Inside View of the Catacombs | 881 |

| Lamps Found in the Catacombs | 884 |

| Tomb Inscription | 896 |

| Painted Ceiling | 906 |

| Chamber of a Catacomb | 909 |

| Frieze from the Arch of Titus | 916 |

| Pentateuch, Written 3200 Years Ago | 921 |

| Shishak and His Captives on Sculptured Wall at Karnac | 935 |

| Portrait of Rehoboam | 936 |

[15]

Address to the Mummy.

In Thebes' streets three thousand years ago,

When the Memnonium was in all its glory,

And time had not begun to overthrow

Those temples, palaces and piles stupendous,

Of which the very ruins are tremendous.

Has hob-a-nobbed with Pharaoh, glass to glass;

Or dropped a half-penny in Homer's hat;

Or doffed thine own to let Queen Dido pass;

Or held, by Solomon's own invitation,

A torch at the great Temple's dedication.

Could tell us what those sightless orbs have seen—

How the world looked when it was fresh and young

And the great deluge still had left it green;

Or was it then so old that history's pages

Contained no record of its early ages?

We have, above ground, seen some strange mutations;

The Roman Empire has begun and ended,

New worlds have risen—we have lost old nations;

And countless kings have into dust been humbled,

While not a fragment of thy flesh has crumbled.

[16] The nature of thy private life unfold:

A heart has throbbed beneath that leathern breast,

And tears adown that dusty cheek have rolled;

Have children climbed those knees and kissed that face?

What was thy name and station, age and race?"

Answer.

A spell that long has bound these lungs of clay,

For since this smoke-dried tongue of mine hath spoken,

Three thousand tedious years have rolled away.

Unswathed at length, I 'stand at ease' before ye.

List, then. O list, while I unfold my story."

* * * * * * * * *

[17]

POMPEII.ToC

Pompeii was in its full glory at the commencement of the Christian era. It was a city of wealth and refinement, with about 35,000 inhabitants, and beautifully located at the foot of Mount Vesuvius; it possessed all local advantages that the most refined taste could desire. Upon the verge of the sea, at the entrance of a fertile plain, on the bank of a navigable river, it united the conveniences of a commercial town with the security of a military station, and the romantic beauty of a spot celebrated in all ages for its pre-eminent loveliness. Its environs, even to the heights of Vesuvius, were covered with villas, and the coast, all the way to Naples, was so ornamented with gardens and villages, that the shores of the whole gulf appeared as one city.

[18]What an enchanting picture must have presented itself to one approaching Pompeii by sea! He beheld the bright, cheerful Grecian temples spreading out on the slopes before him; the pillared Forum; the rounded marble Theatres. He saw the grand Palaces descending to the very edge of the blue waves by noble flights of steps, surrounded with green pines, laurels and cypresses, from amidst whose dark foliage marble statues of gods gleamed whitely.

The skillful architect, the sculptors, the painters, and the casters of bronze were all employed to make Pompeii an asylum of arts; all trades and callings endeavored to grace and beautify the city. The prodigious concourse of strangers who came here in search of health and recreation added new charms and life to the scene.

But behind all this, and encased as it were in a frame, the landscape rose in a gentle slope to the summit of the thundering mountain. But indications were not wanting of the peril with which the city was threatened. The whole district is volcanic; and a few years before the final catastrophe, an earthquake had shaken Pompeii to its foundations; some of the buildings were much injured. On August 24, A.D. 79, the inhabitants were busily engaged in repairing the damage thus wrought, when suddenly and without any previous warning a vast column of black smoke burst from the overhanging mountain. Rising to a prodigious height in the cloudless summer sky, it then gradually spread out like the head of some mighty Italian pine, hiding the sun, and overshadowing the earth for miles in distance.

The darkness grew into profound night, only broken by the blue and sulphurous flashes which darted from the pitchy cloud. Soon the thick rain of thin, light ashes, almost imperceptible to the touch, fell upon the land. Then quickly succeeded shower of small pumice stones and heavier ashes, and emitting stifling eruptic fumes. After a time the sounds of approaching torrent [19]were heard, and soon streaming rivers of dense black mud poured slowly but irresistibly down the mountain sides, and circled through the streets, insidiously creeping into such recesses as even the subtle ashes had failed to penetrate. There was now no place of shelter left. No man could defend himself against this double enemy. It was too late for flight for such as had remained behind. Those who had taken refuge in the innermost parts of the houses, or in the subterranean passages, were closed up forever. Those who sought to flee through the streets were clogged by the small, loose pumice stones, which lay many feet deep, or were entangled and overwhelmed in the mud-streams, or were struck down by the rocks which fell from the heavens. If they escaped these dangers, blinded by the drifting ashes and groping in the dark, not knowing which way to go, they were overcome by the sulphurous vapors, and sinking on the highway were soon buried beneath the volcanic matter. Even many who had gained the open country, at the beginning of the eruption, were overtaken by the darkness and falling cinders, and perished miserably in the field or on the sea-shore, where they had vainly sought the means of flight.

In three days the doomed city had disappeared. It lay buried beneath a vast mass of ashes, pumice stone and hardened mud, from twenty to seventy feet deep. Those of its terror-stricken inhabitants who escaped destruction, abandoned forever its desolate site. Years, generations, centuries went by, and the existence of Pompeii—yea, even its very name—had ceased to be remembered. The rich volcanic soil became covered with a profusion of vegetation. Vineyards flourished and houses were built on the site of the buried city.

Nearly eighteen hundred years had elapsed since the thunderer Vesuvius had thrown the black mantle of ashes over the fair city before the resuscitation arrived. Some antique bronzes and utensils, discovered by a peasant, excited universal attention. [20]Excavations were begun, and Pompeii, shaking off as it were her musty grave clothes, stared from the classic and poetical age of the first into the prosaic modern world of the nineteenth century. The world was startled, and looked with wondering interest to see this ancient stranger arising from her tomb—to behold the awakening of the remote past from the womb of the earth which had so long hoarded it.

The excavation has been assiduously prosecuted, until to-day three hundred and sixty houses, temples, theatres, schools, stores, factories, etc., have been thrown open before us with their treasured contents. It is often, but erroneously, supposed that Pompeii, like Herculaneum, was overwhelmed by a flood of lava. Had this been the case, the work of excavation would have been immensely more difficult, and the result would have been far less important. The marbles must have been calcined, the bronzes melted, the frescoes effaced, and smaller articles destroyed by the fiery flood. The ruin was effected by showers of dust and scoriæ, and by torrents of liquid mud, which formed a mould, encasing the objects, thus preserving them from injury or decay. We thus gain a perfect picture of what a Roman city was eighteen hundred years ago, as everything is laid bare to us in almost a perfect state.

What wealth of splendid vessels and utensils was contained in the chests and closets! Gold and gilded ivory, pearls and precious stones were used to decorate tables, chairs and vessels for eating and drinking. Elegant lamps hung from the ceiling, and candelabra and little lamps of most exquisite shapes illuminated the apartments at night. To-day, looking at the walls, the eyes may feast on beautiful fresco paintings, with colors so vivid and fresh as if painted but yesterday; while gleaming everywhere on ceiling, wall and floor, are marbles of rarest hue, sculptured into every conceivable form of grace and beauty, and inlaid in most artistic designs.

[21]Entering Pompeii.

We will now proceed to describe the general aspect of the city, and for this purpose it will be convenient to suppose that we have entered it by the gate of Herculaneum, though in other respects the Porta della Marina is the more usual and, perhaps, the best entrance.

On entering, the visitor finds himself in a street, running a little east of south, which leads to the Forum. To the right, stands a house formerly owned by a musician; to the left, a thermopolium or shop for hot drinks; beyond is the house of the Vestals; beyond this the custom-house; and a little further on, where another street runs into this one from the north at a very acute angle, stands a public fountain. In the last-named street is a surgeon's house; at least one so named from the quantity of surgical instruments found in it, all made of bronze. On the right or western side of the street, by which we entered, the houses, as we have said, are built on the declivity of a rock, and are several stories high.

The fountain is about one hundred and fifty yards from the city gate. About the same distance, further on, the street divides into two; the right-hand turning seems a by-street, the left-hand turning conducts you to the Forum. The most important feature in this space is a house called the house of Sallust or of Actæon, from a painting in it representing that hunter's death. It stands on an area about forty yards square, and is encompassed on three sides by streets; by that namely which we have been describing, by another nearly parallel to it, and by a third, perpendicular to these two. The whole quarter at present excavated, as far as the Street of the Baths, continued by the Street of Fortune, is divided, by six longitudinal and one transverse street, into what the Romans called islands, or insulated masses [22]of houses. Two of these are entirely occupied by the houses of Pansa and of the Faun, which, with their courts and gardens, are about one hundred yards long by forty wide.

From the Street of the Baths and that of Fortune, which bound these islands on the south, two streets lead to the two corners of the Forum; between them are baths, occupying nearly the whole island. Among other buildings are a milk-shop and gladiatorial school. At the northeast corner of the Forum was a triumphal arch. At the end of the Street of the Baths and beginning of that of Fortune, another triumphal arch is still to be made out, spanning the street of Mercury, so that this was plainly the way of state into the city. The Forum is distant from the gate of Herculaneum about four hundred yards. Of it we shall give a full description in its place. Near the south-eastern corner two streets enter it, one running to the south, the other to the east. We will follow the former for about eighty yards, when it turns eastward for two hundred yards, and conducts us to the quarter of the theatres. The other street, which runs eastward from the Forum, is of more importance, and is called the Street of the Silversmiths;[1] at the end of which a short street turns southwards, and meets the other route to the theatres. On both these routes the houses immediately bordering on the streets are cleared; but between them is a large rectangular plot of unexplored ground. Two very elegant houses at the southwest corner of the Forum were uncovered by the French general Championnet, while in command at Naples, and are known by his name. On the western side of the Forum two streets led down towards the sea; the excavations here consist almost entirely of public buildings, which will be described hereafter.

The quarter of the theatres comprises a large temple, called the Temple of Neptune or Hercules, a temple of Isis, a temple [23]of Æsculapius, two theatres, the Triangular Forum, and the quarters of the soldiers or gladiators. On the north and east it is bounded by streets; to the south and west it seems to have been enclosed partly by the town walls, partly by its own. Here the continuous excavation ends, and we must cross vineyards to [24]the amphitheatre, about five hundred and fifty yards distant from the theatre, in the southeast corner of the city, close to the walls, and in an angle formed by them. Close to the amphitheatre are traces of walls supposed to have belonged to a Forum Boarium, or cattle market. Near at hand, a considerable building, called the villa of Julia Felix, has been excavated and filled up again. On the walls of it was discovered the following inscription, which may serve to convey an idea of the wealth of some of the Pompeian proprietors:

In Praedis Julle Sp F. Felicis

Locantur

Balneum Venerium Et Nongentum Tabernæ Pergulæ

Cœnacula Ex Idibus Aug Primis

In Idus Aug. Sextas Annos Continuos Quinque

S. Q. D. L. E. N. C.

That is: "On the estate of Julia Felix, daughter of Spurius, are to be let a bath, a venereum, nine hundred shops, with booths and garrets, for a term of five continuous years, from the first to the sixth of the Ides of August." The formula, S. Q. D. L. E. N. C., with which the advertisement concludes, is thought to stand for—si quis domi lenocinium exerceat ne conducito: "let no one apply who keeps a brothel."

A little to the south of the smaller theatre was discovered, in 1851, the Gate of Stabiæ. Hence a long straight street, which has been called the Street of Stabiæ, traversed the whole breadth of the city, till it issued out on the northern side at the gate of Vesuvius. It has been cleared to the point where it intersects the Streets of Fortune and of Nola, which, with the Street of the Baths, traverse the city in its length. The Street of Stabiæ forms the boundary of the excavations; all that part of Pompeii which lies to the east of it, with the exception of the amphitheatre, and the line forming the Street of Nola, being still occupied by vineyards and cultivated fields. On the other hand, that part [25]of the city lying to the west of it has been for the most part disinterred; though there are still some portions lying to the south and west of the Street of Abundance and the Forum, and to the east of the Vico Storto, which remain to be excavated.

The streets of Pompeii are paved with large irregular pieces of lava joined neatly together, in which the chariot wheels have worn ruts, still discernible; in some places they are an inch and a half deep, and in the narrow streets follow one track; where the streets are wider, the ruts are more numerous and irregular. The width of the streets varies from eight or nine feet to about twenty-two, including the footpaths or trottoirs. In many places they are so narrow that they may be crossed at one stride; where they are wider, a raised stepping-stone, and sometimes two or three, have been placed in the centre of the crossing. These stones, though in the middle of the carriage way, did not much inconvenience those who drove about in the biga, or two-horsed chariot, as the wheels passed freely in the spaces left, while the horses, being loosely harnessed, might either have stepped over the stones or passed by the sides. The curb-stones are elevated from one foot to eighteen inches, and separate the foot-pavement from the road. Throughout the city there is hardly a street unfurnished with this convenience. Where there is width to admit of a broad foot-path, the interval between the curb and the line of building is filled up with earth, which has then been covered over with stucco, and sometimes with a coarse mosaic of brickwork. Here and there traces of this sort of pavement still remain, especially in those streets which were protected by porticoes.

[26]

Arrangement of Private Houses.

We will now give an account of some of the most remarkable private houses which have been disinterred; of the paintings, domestic utensils, and other articles found in them; and such information upon the domestic manners of the ancient Italians as may seem requisite to the illustration of these remains. This branch of our subject is not less interesting, nor less extensive than the other. Temples and theatres, in equal preservation, and of greater splendor than those at Pompeii, may be seen in many places; but towards acquainting us with the habitations, the private luxuries and elegancies of ancient life, not all the scattered fragments of domestic architecture which exist elsewhere have done so much as this city, with its fellow-sufferer, Herculaneum.

Towards the last years of the republic, the Romans naturalized the arts of Greece among themselves; and Grecian architecture came into fashion at Rome, as we may learn, among other sources, from the letters of Cicero to Atticus, which bear constant testimony to the strong interest which he took in ornamenting his several houses, and mention Cyrus, his Greek architect. At this time immense fortunes were easily made from the spoils of new conquests, or by peculation and maladministration of subject provinces, and the money thus ill and easily acquired was squandered in the most lavish luxury. One favorite mode of indulgence was in splendor of building. Lucius Cassius was the first who ornamented his house with columns of foreign marble; they were only six in number, and twelve feet high. He was [27]soon surpassed by Scaurus, who placed in his house columns of the black marble called Lucullian, thirty-eight feet high, and of such vast and unusual weight that the superintendent of sewers, as we are told by Pliny,[2] took security for any injury which might happen to the works under his charge, before they were suffered to be conveyed along the streets. Another prodigal, by name Mamurra, set the example of lining his rooms with slabs of marble. The best estimate, however, of the growth of architectural luxury about this time may be found in what we are told by Pliny, that, in the year of Rome 676, the house of Lepidus was the finest in the city, and thirty-five years later it was not the hundredth.[3] We may mention, as an example of the lavish expenditure of the Romans, that Domitius Ahenobarbus offered for the house of Crassus a sum amounting to near $242,500, which was refused by the owner.[4] Nor were they less extravagant in their country houses. We may again quote Cicero, whose attachment to his Tusculan and Formian villas, and interest in ornamenting them, even in the most perilous times, is well known. Still more celebrated are the villas of Lucullus and Pollio; of the latter some remains are still to be seen near Pausilipo.

Augustus endeavored by his example to check this extravagant passion, but he produced little effect. And in the palaces of the emperors, and especially the Aurea Domus, the Golden House of Nero, the domestic architecture of Rome, or, we might probably say, of the world, reached its extreme.

The arrangement of the houses, though varied, of course, by local circumstances, and according to the rank and circumstances of the master, was pretty generally the same in all. The principal rooms, differing only in size and ornament, recur everywhere; those supplemental ones, which were invented only for convenience or luxury, vary according to the tastes and circumstances of the master.

[28]The private part comprised the peristyle, bed-chambers, triclinium, œci, picture-gallery, library, baths, exedra, xystus, etc. We proceed to explain the meaning of these terms.

Before great mansions there was generally a court or area, upon which the portico opened, either surrounding three sides of the area, or merely running along the front of the house. In smaller houses the portico ranged even with the street. Within the portico, or if there was no portico, opening directly to the street, was the vestibule, consisting of one or more spacious apartments. It was considered to be without the house, and was always open for the reception of those who came to wait there until the doors should be opened. The prothyrum, in Greek architecture, was the same as the vestibule. In Roman architecture, it was a passage-room, between the outer or house-door which opened to the vestibule, and an inner door which closed the entrance of the atrium. In the vestibule, or in an apartment opening upon it, the porter, ostiarius, usually had his seat.

The atrium, or cavædium, for they appear to have signified the same thing, was the most important, and usually the most splendid apartment of the house. Here the owner received his crowd of morning visitors, who were not admitted to the inner apartments. The term is thus explained by Varro: "The hollow of the house (cavum ædium) is a covered place within the walls, left open to the common use of all. It is called Tuscan, from the Tuscans, after the Romans began to imitate their [29]cavædium. The word atrium is derived from the Atriates, a people of Tuscany, from whom the pattern of it was taken." Originally, then, the atrium was the common room of resort for the whole family, the place of their domestic occupations; and such it probably continued in the humbler ranks of life. A general description of it may easily be given. It was a large apartment, roofed over, but with an opening in the centre, called compluvium, towards which the roof sloped, so as to throw the rain-water into a cistern in the floor called impluvium.

The roof around the compluvium was edged with a row of highly ornamented tiles, called antefixes, on which a mask or some other figure was moulded. At the corners there were usually spouts, in the form of lions' or dogs' heads, or any fantastical device which the architect might fancy, which carried the rain-water clear out into the impluvium, whence it passed into cisterns; from which again it was drawn for household purposes. For drinking, river-water, and still more, well-water, was preferred. Often the atrium was adorned with fountains, supplied through leaden or earthenware pipes, from aqueducts or other raised heads of water; for the Romans knew the property of fluids, which causes them to stand at the same height in communicating vessels. This is distinctly recognized by Pliny,[5] though their common use of aqueducts, in preference to pipes, has led to a supposition that this great hydrostatical principle was unknown to them. The breadth of the impluvium, according to Vitruvius, was not less than a quarter, nor greater than a third, of the whole breadth of the atrium; its length was regulated by the same standard. The opening above it was often shaded by a colored veil, which diffused a softened light, and moderated the intense heat of an Italian sun.[6] The splendid columns of the house of [30]Scaurus, at Rome, were placed, as we learn from Pliny,[7] in the atrium of his house. The walls were painted with landscapes or arabesques—a practice introduced about the time of Augustus—or lined with slabs of foreign and costly marbles, of which the Romans were passionately fond. The pavement was composed of the same precious material, or of still more valuable mosaics.

The tablinum was an appendage of the atrium, and usually entirely open to it. It contained, as its name imports,[8] the family archives, the statues, pictures, genealogical tables, and other relics of a long line of ancestors.

Alæ, wings, were similar but smaller apartments, or rather recesses, on each side of the further part of the atrium. Fauces, jaws, were passages, more especially those which passed to the interior of the house from the atrium.

[31]In houses of small extent, strangers were lodged in chambers which surrounded and opened into the atrium. The great, whose connections spread into the provinces, and who were visited by numbers who, on coming to Rome, expected to profit by their hospitality, had usually a hospitium, or place of reception for strangers, either separate, or among the dependencies of their palaces.

Of the private apartments the first to be mentioned is the peristyle, which usually lay behind the atrium, and communicated with it both through the tablinum and by fauces. In its general plan it resembled the atrium, being in fact a court, open to the sky in the middle, and surrounded by a colonnade, but it was larger in its dimensions, and the centre court was often decorated with shrubs and flowers and fountains, and was then called xystus. It should be greater in extent when measured transversely than in length,[9] and the intercolumniations should not exceed four, nor fall short of three diameters of the columns.

Of the arrangement of the bed-chambers we know little. They seem to have been small and inconvenient. When there was room they had usually a procœton, or ante-chamber. Vitruvius recommends that they should face the east, for the benefit of the early sun. One of the most important apartments in the whole house was the triclinium, or dining-room, so named from the three beds, which encompassed the table on three sides, leaving the fourth open to the attendants. The prodigality of the Romans in matters of eating is well known, and it extended to all matters connected with the pleasures of the table. In their rooms, their couches, and all the furniture of their entertainments, magnificence and extravagance were carried to their highest point. The rich had several of these apartments, to be used at different seasons, or on various occasions. Lucullus, celebrated for his wealth and profuse expenditure, had a certain [32]standard of expenditure for each triclinium, so that when his servants were told which hall he was to sup in, they knew exactly the style of entertainment to be prepared; and there is a well-known story of the way in which he deceived Pompey and Cicero, when they insisted on going home with him to see his family supper, by merely sending word home that he would sup in the Apollo, one of the most splendid of his halls, in which he never gave an entertainment for less than 50,000 denarii, about $8,000. Sometimes the ceiling was contrived to open and let down a second course of meats, with showers of flowers and perfumed waters, while rope-dancers performed their evolutions over the heads of the company. The performances of these funambuli are frequently represented in paintings at Pompeii. Mazois, in his work entitled "Le Palais de Scaurus," has given a fancy picture of the habitation of a Roman noble of the highest class, in which he has embodied all the scattered notices of domestic life, which a diligent perusal of the Latin writers has enabled him to collect. His description of the triclinium of Scaurus will give the reader the best notion of the style in which such an apartment was furnished and ornamented. For each particular in the description he quotes some authority. We shall not, however, encumber our pages with references to a long list of books not likely to be in the possession of most readers.

"Bronze lamps,[10] dependent from chains of the same metal, or raised on richly-wrought candelabra, threw around the room a brilliant light. Slaves set apart for this service watched them, trimmed the wicks, and from time to time supplied them with oil.

"The triclinium is twice as long as it is broad, and divided, as it were, into two parts—the upper occupied by the table and the couches, the lower left empty for the convenience of the attendants and spectators. Around the former the walls, up to [33]a certain height, are ornamented with valuable hangings. The decorations of the rest of the room are noble, and yet appropriate to its destination; garlands, entwined with ivy and vine-branches, divide the walls into compartments bordered with fanciful ornaments; in the centre of each of which are painted with admirable elegance young Fauns, or half-naked Bacchantes, carrying thyrsi, vases and all the furniture of festive meetings. Above the columns is a large frieze, divided into twelve compartments; each of these is surmounted by one of the signs of the Zodiac, and contains paintings of the meats which are in highest season in each month; so that under Sagittary (December), we see shrimps, shell-fish, and birds of passage; under Capricorn (January), lobsters, sea-fish, wild-boar and game; under Aquarius (February), ducks, plovers, pigeons, water-rails, etc.

"The table, made of citron wood[11] from the extremity of Mauritania, more precious than gold, rested upon ivory feet, and was covered by a plateau of massive silver, chased and carved, weighing five hundred pounds. The couches, which would contain thirty persons, were made of bronze overlaid with ornaments in silver, gold and tortoise-shell; the mattresses of Gallic wool, [34]dyed purple; the valuable cushions, stuffed with feathers, were covered with stuffs woven and embroidered with silk mixed with threads of gold. Chrysippus told us that they were made at Babylon, and had cost four millions of sesterces.[12]

"The mosaic pavement, by a singular caprice of the architect, represented all the fragments of a feast, as if they had fallen in common course on the floor; so that at the first glance the room seemed not to have been swept since the last meal, and it was called from hence, asarotos oikos, the unswept saloon. At the bottom of the hall were set out vases of Corinthian brass. This triclinium, the largest of four in the palace of Scaurus, would easily contain a table of sixty covers;[13] but he seldom brings together so large a number of guests, and when on great occasions he entertains four or five hundred persons, it is usually in the atrium. This eating-room is reserved for summer; he has others for spring, autumn, and winter, for the Romans turn the change of season into a source of luxury. His establishment is so appointed that for each triclinium he has a great number of tables of different sorts, and each table has its own service and its particular attendants.

"While waiting for their masters, young slaves strewed over the pavement saw-dust dyed with saffron and vermilion, mixed with a brilliant powder made from the lapis specularis, or talc."

Pinacotheca, the picture-gallery, and Bibliotheca, the library, need no explanation. The latter was usually small, as a large number of rolls (volumina) could be contained within a narrow space.

Exedra bore a double signification. It is either a seat, intended to contain a number of persons, like those before the Gate [35]of Herculaneum, or a spacious hall for conversation and the general purposes of society. In the public baths, the word is especially applied to those apartments which were frequented by the philosophers.

Such was the arrangement, such the chief apartments of a Roman house; they were on the ground-floor, the upper stories being for the most part left to the occupation of slaves, freedmen, and the lower branches of the family. We must except, however, the terrace upon the top of all (solarium), a favorite place of resort, often adorned with rare flowers and shrubs, planted in huge cases of earth, and with fountains and trellises, under which the evening meal might at pleasure be taken.

The reader will not, of course, suppose that in all houses all these apartments were to be found, and in the same order. From the confined dwelling of the tradesman to the palace of the patrician, all degrees of accommodation and elegance were to be found. The only object of this long catalogue is to familiarize the reader with the general type of those objects which we are about to present to him, and to explain at once, and collectively, those terms of art which will be of most frequent occurrence.

The reader will gain a clear idea of a Roman house from the ground-plan of that of Diomedes, given a little further on, which is one of the largest and most regularly constructed at Pompeii.

We may here add a few observations, derived, as well as much of the preceding matter, from the valuable work of Mazois, relative to the materials and method of construction of the Pompeian houses. Every species of masonry described by Vitruvius, it is said, may here be met with; but the cheapest and most durable sorts have been generally preferred.

Copper, iron, lead, have been found employed for the same purposes as those for which we now use them. Iron is more plentiful than copper, contrary to what is generally observed in [36]ancient works. It is evident from articles of furniture, etc., found in the ruins, that the Italians were highly skilled in the art of working metals, yet they seem to have excelled in ornamental work, rather than in the solid and neat construction of useful articles. For instance, their lock-work is coarse, hardly equal to that which is now executed in the same country; while the external ornaments of doors, bolts, handles, etc., are elegantly wrought.

The first private house that we will describe is found by passing down a street from the Street of Abundance. The visitor finds on the right, just beyond the back wall of the Thermæ Stabianæ, the entrance of a handsome dwelling. An inscription in red letters on the outside wall containing the name of Siricus has occasioned the conjecture that this was the name of the owner of the house; while a mosaic inscription on the floor of the prothyrum, having the words Salve Lucru, has given rise to a second appellation for the dwelling.

On the left of the prothyrum is an apartment with two doors, one opening on a wooden staircase leading to an upper floor, the other forming the entry to a room next the street, with a window like that described in the other room next the prothyrum. The walls of this chamber are white, divided by red and yellow zones into compartments, in which are depicted the symbols of the principal deities—as the eagle and globe of Jove, the peacock of Juno, the lance, helmet and shield of Minerva, the panther of Bacchus, a Sphinx, having near it the mystical chest and sistrum of Isis, who was the Venus Physica of the Pompeians, the caduceus and other emblems of Mercury, etc. There are also two small landscapes.

Next to this is a large and handsome exedra, decorated with good pictures, a third of the size of life. That on the left represents Neptune and Apollo presiding at the building of Troy; the former, armed with his trident, is seated; the latter, crowned [37]with laurel, is on foot, and leans with his right arm on a lyre. On the wall opposite to this is a picture of Vulcan presenting the arms of Achilles to Thetis. The celebrated shield is supported by Vulcan on the anvil, and displayed to Thetis, who is seated, whilst a winged female figure standing at her side points out to her with a rod the marvels of its workmanship. Agreeably to the Homeric description the shield is encircled with the signs of the zodiac, and in the middle are the bear, the dragon, etc. On the ground are the breast-plate, the greaves and the helmet.

In the third picture is seen Hercules crowned with ivy, inebriated, and lying on the ground at the foot of a cypress tree. [38]He is clothed in a sandyx, or short transparent tunic, and has on his feet a sort of shoes, one of which he has kicked off. He supports himself on his left arm, while the right is raised in drunken ecstasy. A little Cupid plucks at his garland of ivy, another tries to drag away his ample goblet. In the middle of the picture is an altar with festoons. On the top of it three Cupids, assisted by another who has climbed up the tree, endeavor to bear on their shoulders the hero's quiver; while on the ground, to the left of the altar, four other Cupids are sporting with his club. A votive tablet with an image of Bacchus rests at the foot of the altar, and indicates the god to whom Hercules has been sacrificing.

On the left of the picture, on a little eminence, is a group of three females round a column having on its top a vase. The chief and central figure, which is naked to the waist, has in her hand a fan; she seems to look with interest on the drunken hero, but whom she represents it is difficult to say. On the right, half way up a mountain, sits Bacchus, looking on the scene with a complacency not unmixed with surprise. He is surrounded by his usual rout of attendants, one of whom bears a thyrsus. The annexed engraving will convey a clearer idea of the picture, which for grace, grandeur of composition, and delicacy and freshness of coloring, is among the best discovered at Pompeii. The exedra is also adorned with many other paintings and ornaments which it would be too long to describe.

On the same side of the atrium, beyond a passage leading to a kitchen with an oven, is an elegant triclinium fenestratum looking upon an adjacent garden. The walls are black, divided by red and yellow zones, with candelabra and architectural members intermixed with quadrupeds, birds, dolphins, Tritons, masks, etc., and in the middle of each compartment is a Bacchante. In each wall are three small paintings executed with greater care. [39]The first, which has been removed, represented Æneas in his tent, who, accompanied by Mnestheus, Achates, and young Ascanius, presents his thigh to the surgeon, Iapis, in order to extract from it the barb of an arrow. Æneas supports himself with the lance in his right hand, and leans with the other on the shoulder of his son, who, overcome by his father's misfortune, wipes the tears from his eyes with the hem of his robe; while Iapis, kneeling on one leg before the hero, is intent on extracting the barb with his forceps. But the wound is not to be healed without divine interposition. In the background of the picture Venus is hastening to her son's relief, bearing in her hand the branch of dictamnus, which is to restore him to his pristine vigor.

The subject of the second picture, which is much damaged, is not easy to be explained. It represents a naked hero, armed with sword and spear, to whom a woman crowned with laurel and clothed in an ample peplum is pointing out another female figure. The latter expresses by her gestures her grief and indignation at the warrior's departure, the imminence of which is signified by the chariot that awaits him. Signor Fiorelli thinks he recognizes in this picture Turnus, Lavinia, and Amata, when the queen supplicates Turnus not to fight with the Trojans.

The third painting represents Hermaphroditus surrounded by six nymphs, variously employed.

From the atrium a narrow fauces or corridor led into the garden. Three steps on the left connected this part of the house with the other and more magnificent portion having its entrance from the Strada Stabiana. The garden was surrounded on two sides with a portico, on the right of which are some apartments which do not require particular notice.

The house entered at a higher level, by the three steps just mentioned, was at first considered as a separate house, and by Fiorelli has been called the House of the Russian Princes, from some excavations made here in 1851 in presence of the sons [40]of the Emperor of Russia. The peculiarities observable in this house are that the atrium and peristyle are broader than they are deep, and that they are not separated by a tablinum and other rooms, but simply by a wall. In the centre of the Tuscan atrium, entered from the Street of Stabiæ, is a handsome marble impluvium. At the top of it is a square cippus, coated with marble, and having a leaden pipe which flung the water into a square vase or basin supported by a little base of white marble, ornamented with acanthus leaves. Beside the fountain is a table of the same material, supported by two legs beautifully sculptured, of a chimæra and a griffin. On this table was a little bronze group of Hercules armed with his club, and a young Phrygian kneeling before him.

From the atrium the peristyle is entered by a large door. It is about forty-six feet broad and thirty-six deep, and has ten columns, one of which still sustains a fragment of the entablature. The walls were painted in red and yellow panels alternately, with figures of Latona, Diana, Bacchantes, etc. At the bottom of the peristyle, on the right, is a triclinium. In the middle is a small œcus, with two pillars richly ornamented with arabesques. A little apartment on the left has several pictures.

In this house, at a height of seventeen Neapolitan palms (nearly fifteen feet) from the level of the ground, were discovered four skeletons together in an almost vertical position. Twelve palms lower was another skeleton, with a hatchet near it. This man appears to have pierced the wall of one of the small chambers of the prothyrum, and was about to enter it, when he was smothered, either by the falling in of the earth or by the mephitic exhalations. It has been thought that these persons perished while engaged in searching for valuables after the catastrophe.

In the back room of a thermopolium not far from this spot was discovered a graffito of part of the first line of the Æneid, in which the rs were turned into ls:

Alma vilumque cano Tlo.

[41]We will now return to the house of Siricus. Contiguous to it in the Via del Lupanare is a building having two doors separated with pilasters. By way of sign, an elephant was painted on the wall, enveloped by a large serpent and tended by a pigmy. Above was the inscription: Sittius restituit elephantum; and beneath the following:

Hospitium hic locatur

Triclinium cum tribus lectis

Et comm.

Both the painting and the inscription have now disappeared. The discovery is curious, as proving that the ancients used signs for their taverns. Orelli has given in his Inscriptions in Gaul, one of a Cock (a Gallo Gallinacio). In that at Pompeii the last word stands for "commodis." "Here is a triclinium with three beds and other conveniences."

Just opposite the gate of Siricus was another house also supposed to be a caupona, or tavern, from some chequers painted on the door posts. On the wall are depicted two large serpents, the emblem so frequently met with. They were the symbols of the Lares viales, or compitales, and, as we have said, rendered the place sacred against the commission of any nuisance. The cross, which is sometimes seen on the walls of houses in a modern Italian city, serves the same purpose. Above the serpents is the following inscription, in tolerably large white characters: Otiosis locus hic non est, discede morator. "Lingerer, depart; this is no place for idlers." An injunction by the way which seems rather to militate against the idea of the house having been a tavern.

The inscription just mentioned suggests an opportunity for giving a short account of similar ones; we speak not of inscriptions cut in stone, and affixed to temples and other public buildings, but such as were either painted, scrawled in charcoal and other substances, or scratched with a sharp point, such as a nail [42]or knife, on the stucco of walls and pillars. Such inscriptions afford us a peep both into the public and the domestic life of the Pompeians. Advertisements of a political character were commonly painted on the exterior walls in large letters in black and red paint; poetical effusions or pasquinades, etc., with coal or chalk (Martial, Epig. xii. 61, 9); while notices of a domestic kind are more usually found in the interior of the houses, scratched, as we have said, on the stucco, whence they have been called graffiti.

The numerous political inscriptions bear testimony to the activity of public life in Pompeii. These advertisements, which for the most part turn on the election of ædiles, duumvirs, and other magistrates, show that the Pompeians, at the time when their city was destroyed, were in all the excitement of the approaching comitia for the election of such magistrates. We shall here select a few of the more interesting inscriptions, both relating to public and domestic matters.

It seems to have been customary to paint over old advertisements with a coat of white, and so to obtain a fresh surface for new ones, just as the bill-sticker remorselessly pastes his bill over that of some brother of the brush. In some cases this new coating has been detached, or has fallen off, thus revealing an older notice, belonging sometimes to a period antecedent to the Social War. Inscriptions of this kind are found only on the solid stone pillars of the more ancient buildings, and not on the stucco, with which at a later period almost everything was plastered. Their antiquity is further certified by some of them being in the Oscan dialect; while those in Latin are distinguished from more recent ones in the same language by the forms of the letters, by the names which appear in them, and by archaisms in grammar and orthography. Inscriptions in the Greek tongue are rare, though the letters of the Greek alphabet, scratched on walls at a little height from the ground, and thus evidently the work of [43]school-boys, show that Greek must have been extensively taught at Pompeii.

The normal form of electioneering advertisements contains the name of the person recommended, the office for which he is a candidate, and the name of the person, or persons, who recommended him, accompanied in general with the formula O. V. F. From examples written in full, recently discovered, it appears that these letters mean orat (or orant) vos faciatis: "beseech you to create" (ædile and so forth). The letters in question were, before this discovery, very often thought to stand for orat ut faveat, "begs him to favor;" and thus the meaning of the inscription was entirely reversed, and the person recommending converted into the person recommended. In the following example for instance—M. Holconium Priscum duumvirum juri dicundo O. V. F. Philippus; the meaning, according to the older interpretation, will be: "Philippus beseeches M. Holconius Priscus, duumvir of justice, to favor or patronize him;" whereas the true sense is: "Philippus beseeches you to create M. Holconius Priscus a duumvir of justice." From this misinterpretation wrong names have frequently been given to houses; as is probably the case, for instance, with the house of Pansa, which, from the tenor of the inscription, more probably belonged to Paratus, who posted on his own walls a request to passers-by to make his friend Pansa ædile. Had it been the house of Pansa, when a candidate for the ædileship, and if it was the custom for such candidates to post recommendatory notices on their doors, it may be supposed that Pansa would have exhibited more than this single one from a solitary friend. This is a more probable meaning than that Paratus solicited in this way the patronage of Pansa; for it would have been a bad method to gain it by disfiguring his walls in so impertinent a manner. We do not indeed mean to deny that adulatory inscriptions were sometimes written on the houses or doors of powerful or popular men or pretty women. A verse of [44]Plautus bears testimony to such a custom (Impleantur meæ foreis elogiorum carbonibus. Mercator, act ii. sc. 3). But first, the inscription on the so-called house of Pansa was evidently not of an adulatory, but of a recommendatory character; and secondly, those of the former kind, as we learn from this same verse, seem to have been written by passing admirers, with some material ready to the hand, such as charcoal or the like, and not painted on the walls with care, and time, and expense; a proceeding which we can hardly think the owner of the house, if he was a modest and sensible man, would have tolerated.

Recommendations of candidates were often accompanied with a word or two in their praise; as dignus, or dignissimus est, probissimus, juvenis integer, frugi, omni bono meritus, and the like. Such recommendations are sometimes subscribed by guilds or corporations, as well as by private persons, and show that there were a great many such trade unions at Pompeii. Thus we find mentioned the offectores (dyers), pistores (bakers), aurifices (goldsmiths), pomarii (fruiterers), cæparii (green-grocers), lignarii (wood merchants), plostrarii (cart-wrights), piscicapi (fishermen), agricolæ (husbandmen), muliones (muleteers), culinarii (cooks), fullones (fullers), and others. Advertisements of this sort appear to have been laid hold of as a vehicle for street wit, just as electioneering squibs are perpetrated among ourselves. Thus we find mentioned, as if among the companies, the pilicrepi (ball-players), the seribibi (late topers), the dormientes universi (all the worshipful company of sleepers), and as a climax, Pompeiani universi (all the Pompeians, to a man, vote for so and so). One of these recommendations, purporting to emanate from a "teacher" or "professor," runs, Valentius cum discentes suos (Valentius with his disciples); the bad grammar being probably intended as a gibe upon one of the poor man's weak points.

The inscriptions in chalk and coal, the graffiti, and [45]occasionally painted inscriptions, contain sometimes well-known verses from poets still extant. Some of these exhibit variations from the modern text, but being written by not very highly educated persons, they seldom or never present any various readings that it would be desirable to adopt, and indeed contain now and then prosodical errors. Other verses, some of them by no means contemptible, are either taken from pieces now lost, or are the invention of the writer himself. Many of these inscriptions are of course of an amatory character; some convey intelligence of not much importance to anybody but the writer—as, that he is troubled with a cold—or was seventeen centuries ago—or that he considers somebody who does not invite him to supper as no better than a brute and barbarian, or invokes blessings on the man that does. Some are capped by another hand with a biting sarcasm on the first writer, and many, as might be expected, are scurrilous and indecent. Some of the graffiti on the interior walls and pillars of houses are memoranda of domestic transactions; as, how much lard was bought, how many tunics sent to the wash, when a child or a donkey was born, and the like. One of this kind, scratched on the wall of the peristyle of the corner house in the Strada della Fortuna and Vicolo degli Scienziati, appears to be an account of the dispensator or overseer of the tasks in spinning allotted to the female slaves of the establishment, and is interesting as furnishing us with their names, which are Vitalis, Florentina, Amarullis, Januaria, Heracla, Maria (Maria, feminine of Marius, not Maria), Lalagia (reminding us of Horace's Lalage), Damalis, and Doris. The pensum, or weight of wool delivered to each to be spun, is spelled pesu, the n and final m being omitted, just as we find salve lucru, for lucrum, written on the threshold of the house of Siricus. In this form, pesu is very close to the Italian word peso.

We have already alluded now and then to the rude etchings and caricatures of these wall-artists, but to enter fully into the [46]subject of the Pompeian inscriptions and graffiti would almost demand a separate volume, and we must therefore resume the thread of our description.

A little beyond the house of Siricus, a small street, running down at right angles from the direction of the Forum, enters the Via del Lupanare. Just at their junction, and having an entrance into both, stands the Lupanar, from which the latter street derives its name. We can not venture upon a description of this resort of Pagan immorality. It is kept locked up, but the guide will procure the key for those who may wish to see it. Next to it is the House of the Fuller, in which was found the elegant little bronze statuette of Narcissus, now in the Museum. The house contained nothing else of interest.

The Via del Lupanare terminates in the Street of the Augustals, or of the Dried Fruits. In this latter street, nearly opposite the end of the Via del Lupanare, but a little to the left, is the House of Narcissus, or of the Mosaic Fountain. This house is one of recent excavation. At the threshold is a Mosaic of a bear, with the word Have. The prothyrum is painted with figures on a yellow ground. On the left is a medallion of a satyr and nymph; the opposite medallion is destroyed.

The atrium is paved with mosaic. The first room on the right-hand side of it has a picture of Narcissus admiring himself in the water. The opposite picture has a female figure seated, with a child in her arms, and a large chest open before her. The tablinum is handsomely paved with mosaic and marble. Behind this, in place of a peristyle, is a court or garden, the wall of which is painted with a figure bearing a basin. At the bottom is a handsome mosaic fountain, from which the house derives one of its names, with a figure of Neptune surrounded by fishes and sea-fowl; above are depicted large wild boars.

On the opposite side of the way, at the eastern angle of the Street of the Lupanar, is the House of the Rudder and Trident, [47]also called the House of Mars and Venus. The first of these names is derived from the mosaic pavement in the prothyrum, in which the objects mentioned are represented; while a medallion picture in the atrium, with heads of Mars and Venus, gave rise to the second appellation. The colors of this picture are still quite fresh, a result which Signor Fiorelli attributes to his having caused a varnish of wax to be laid over the painting at the time of its discovery. Without some such protection the colors of these pictures soon decay; the cinnabar, or vermilion, especially, turns black after a few days' exposure to the light.

The atrium, as usual, is surrounded with bed-chambers. A peculiarity not yet found in any other house is a niche or closet on the left of the atrium, having on one side an opening only large enough to introduce the hand, whence it has been conjectured that it served as a receptacle for some valuable objects. It is painted inside with a wall of quadrangular pieces of marble of various colors, terminated at top with a cornice. In each of the squares is a fish, bird, or quadruped.

This closet or niche stands at a door of the room in which is an entrance to a subterranean passage, having its exit in the Via del Lupanare. There is nothing very remarkable in the other apartments of this house. Behind is a peristyle with twelve columns, in the garden of which shrubs are said to have been discovered in a carbonized state.

Further down the same Street of the Augustals, at the angle which it forms with the Street of Stabiæ, is the house of a baker, having on the external wall the name Modestum in red letters. For a tradesman it seems to have been a comfortable house, having an atrium and fountain, and some painted chambers. Beyond the atrium is a spacious court with mills and an oven. The oven was charged with more than eighty loaves, the forms of which are still perfect, though they are reduced to a carbonaceous state. They are preserved in the Museum.

[48]The narrow street to which we have alluded, as entering the Via del Lupanare nearly opposite to the house of Siricus, has been called the Via del Balcone, from a small house with a projecting balcony or mænianum. Indications of balconies have been found elsewhere, and indeed there were evidently some in the Via del Lupanare; but this is the only instance of one restored to its pristine state, through the care of Signor Fiorelli in substituting fresh timbers for those which had become carbonized. The visitor may ascend to the first floor of this house, from which the balcony projects several feet into the narrow lane. In the atrium of this house is a very pretty fountain.

The house next to that of the Balcony, facing the entrance of a small street leading from the Via dell Abbondanza, and numbered 7 on the door post, has a few pictures in a tolerable state of preservation. In a painting in the furthest room on the left of the atrium Theseus is seen departing in his ship; Ariadne, roused from sleep, gazes on him with despair, while a little weeping Cupid stands by her side. In the same apartment are two other well-preserved pictures, the subjects of which it is not easy to explain. In one is a female displaying to a man two little figures in a nest, representing apparently the birth of the Dioscuri. The other is sometimes called the Rape of Helen. There are also several medallion heads around.

In the small street which runs parallel with the eastern side of the Forum, called the Vico di Eumachia, is a house named the Casa nuova della Caccia, to distinguish it from one of the same name previously discovered. As in the former instance, its appellation is derived from a large painting on the wall of the peristyle, of bears, lions, and other animals. On the right-hand wall of the tablinum is a picture of Bacchus discovering Ariadne. A satyr lifts her vest, while Silenus and other figures look on in admiration. The painting on the left-hand wall is destroyed. On entering the peristyle a door on the right leads down some [49]steps into a garden, on one side of which is a small altar before a wall, on which is a painting of shrubs.

Proceeding from this street into the Vico Storto, which forms a continuation of it on the north, we find on the right a recently excavated house, which, from several slabs of variously colored marbles found in it, has been called the House of the Dealer in Marbles. Under a large court in the interior, surrounded with Doric columns, are some subterranean apartments, in one of which was discovered a well more than eighty feet deep and still supplied with fresh water; almost the only instance of the kind at Pompeii. The beautiful statuette of Silenus, already described, was found in this house. Here also was made the rare discovery of the skeletons of two horses, with the remains of a biga.

This description might be extended, but it would be tedious to repeat details of smaller and less interesting houses, the features of which present in general much uniformity; and we shall therefore conclude this account of the more recent discoveries with a notice of a group of bodies found in this neighborhood, the forms of which have been preserved to us through the ingenuity of Signor Fiorelli.

It has already been remarked that the showers of lapillo, or pumice stone, by which Pompeii was overwhelmed and buried, were followed by streams of a thick, tenacious mud, which flowing over the deposit of lapillo, and filling up all the crannies and interstices into which that substance had not been able to penetrate, completed the destruction of the city. The objects over which this mud flowed were enveloped in it as in a plaster mould, and where these objects happened to be human bodies, their decay left a cavity in which their forms were as accurately preserved and rendered as in the mould prepared for the casting of a bronze statue. Such cavities had often been observed. In some of them remnants of charred wood, accompanied with [50]bronze or other ornaments, showed that the object inclosed had been a piece of furniture; while in others, the remains of bones and of articles of apparel evinced but too plainly that the hollow had been the living grave which had swallowed up some unfortunate human being. In a happy moment the idea occurred to Signor Fiorelli of filling up these cavities with liquid plaster, and thus obtaining a cast of the objects which had been inclosed in them. The experiment was first made in a small street leading from the Via del Balcone Pensile towards the Forum. The bodies here found were on the lapillo at a height of about fifteen feet from the level of the ground.

"Among the first casts thus obtained were those of four human beings. They are now preserved in a room at Pompeii, and more ghastly and painful, yet deeply interesting and touching objects, it is difficult to conceive. We have death itself moulded and cast—the very last struggle and final agony brought before us. They tell their story with a horrible dramatic truth that no sculptor could ever reach. They would have furnished a thrilling episode to the accomplished author of the 'Last Days of Pompeii.'