WORKS BY SAMUEL ADAMS DRAKE

—————

OLD LANDMARKS AND HISTORIC PERSONAGESOF BOSTON. Illustrated $2.00

OLD LANDMARKS AND HISTORIC FIELDS OF MIDDLESEX. Illustrated 2.00

NOOKS AND CORNERS OF THE NEW ENGLAND COAST. Illustrated 3.50

CAPTAIN NELSON A Romance of Colonial Days .75

THE HEART OF THE WHITE MOUNTAINS. Illustrated (Illuminated Cloth) 7.50

Tourist's Edition 3.00

AROUND THE HUB. A Boy's Book about Boston. Illustrated 1.50

NEW ENGLAND LEGENDS AND FOLK LORE. Illustrated 2.00

THE MAKING OF NEW ENGLAND. Illustrated 1.50

THE MAKING OF THE GREAT WEST 1.75

OLD BOSTON TAVERNS. Paper .50

BURGOYNE'S INVASION OF 1777 .50

THE TAKING OF LOUISBURG .50

Any book on the above list sent by mail, postpaid, on receipt of price, by

LEE AND SHEPARD, BOSTON

GEORGE GORDON MEADE

Decisive Events in American History

THE

BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG

1863

BY

SAMUEL ADAMS DRAKE

AUTHOR OF "BURGOYNE'S INVASION," "TAKING OF

LOUISBURG," ETC.

"The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here"

Abraham Lincoln

BOSTON

LEE AND SHEPARD PUBLISHERS

10 Milk Street

1892

Copyright, 1891

By LEE AND SHEPARD

THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG

PRESS OF

Rockwell and Churchill

BOSTON

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Gettysburg | 9 |

| II. | The March into Pennsylvania | 23 |

| III. | First Effects of the Invasion | 34 |

| IV. | Reynolds | 46 |

| V. | The First of July | 60 |

| VI. | Cemetery Hill | 81 |

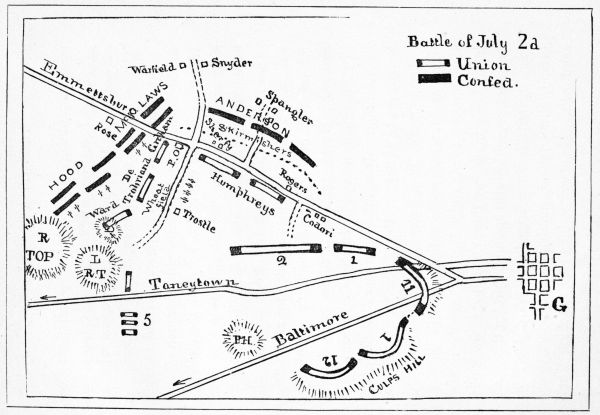

| VII. | The Second of July | 97 |

| VIII. | The Second of July—continued | 112 |

| IX. | The Third of July | 132 |

| X. | The Retreat | 150 |

| XI. | Things by the Way | 160 |

THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG

1863

I

Gettysburg[1]

Stripped of the glamour which has made its every stick and stone an object of eager curiosity or pious veneration, Gettysburg becomes a very plain, matter-of-fact Pennsylvania town, of no particular antiquity, with a very decided Dutch flavor in the names and on the tongues of its citizens, where no great man has ever flourished, or anything had happened to cause its own name to be noised abroad, until one day in the eventful year 1863—the battle year—fame was suddenly thrust upon it, as one might say, not for a day, but for all time. The dead who sleep in the National Cemetery[2] here, or who lie in unknown graves about the[10] fields and woods, and counting many times more than the living, help us to understand how much greater was the battle of Gettysburg than the town which has given it its name.

Gettysburg is the market town—or borough, accurately speaking—of an exclusively farming population, planted in one of the most productive sections of the Keystone State. It is the seat of justice of the county. It has a seminary and college of the German Lutheran Church, which give a certain tone and cast to its social life. In short, Gettysburg seems in all things so entirely devoted to the pursuits of peace, there is so little that is suggestive of war and bloodshed, even if time had not mostly effaced all traces of that gigantic struggle,[3] that, coming as we do with one absorbing idea in mind, we find it hard to reconcile the facts of history with the facts as we find them.

There is another side to Gettysburg—a picturesque, a captivating side. One looks around upon the landscape with simple admiration. One's highest praise comes from the feeling of quiet satisfaction with which the harmony of nature reveals the harmony of God.[11] You are among the subsiding swells that the South Mountain has sent rippling off to the east. So completely is the village hid away among these green swells that neither spire nor steeple is seen until, upon turning one of the numerous low ridges by which the face of the country is so cut up, you enter a valley, not deep, but well defined by two opposite ranges of heights, and Gettysburg lies gleaming in the declining sun before you—a picture to be long remembered.

Its situation is charming. Here and there a bald ridge or wooded hill, the name of which you do not yet know, is pushed or bristles up above the undulating prairie-land, but there is not one really harsh feature in the landscape. In full view off to the northwest, but softened by the gauzy haze of a midsummer's afternoon, the towering bulk of the South Mountain, vanguard of the serried chain behind it, looms imposingly up between Gettysburg and the Cumberland Valley, still beyond, in the west, as landmark for all the country round, as well as for the great battlefield now spreading out its long leagues before you; a monument more aged than the Pyramids,[12] which Napoleon, a supremely imaginative and magnetic man himself, sought to invest with a human quality in the minds of his veterans, when he said to them, "Soldiers! from the summits of yonder Pyramids forty ages behold you." In short, the whole scene is one of such quiet pastoral beauty, the village itself with its circlet of fields and farms so free from every hint of strife and carnage, that again and again we ask ourselves if it can be true that one of the greatest conflicts of modern times was lost and won here.

Yet this, and this alone, is what has caused Gettysburg, the obscure country village, to be inscribed on the same scroll with Blenheim, and Waterloo, and Saratoga, as a decisive factor in the history of the nations. Great deeds have lifted it to monumental proportions. As Abraham Lincoln so beautifully said when dedicating the National Cemetery here, "The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it far above our power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here."

Those noble words ought to be the guiding inspiration of every one who intends adding his own feeble impressions of this great battle to what has been said before.

The strategic importance that Gettysburg suddenly assumed during Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania, in July, 1863, first demands a little of our attention. Yet it seems certain that neither Meade nor Lee had thought of it as a possible battle-ground until accident thrust it upon them. At his first setting out on this campaign Lee had not been able to say, with the map before him, "I will fight a battle either in this or that place," because he had marched not toward, but away from, his adversary, and, so far as can be known, without choosing beforehand a position where Meade would have to come and attack him. For his part, so long as Meade was only following Lee about, the Union general cannot be said to have had much voice in the matter. It was Lee who was really directing Meade's march. True enough, Meade did select a battlefield, but not here, at Gettysburg; nor do we know, nor would it be useful to inquire, whether[14] Lee could have been induced to fight just where Meade wanted him to. As Lee fought at Gettysburg only because he was struck, it is probably beyond any man's power to say that if this had not happened, as it did, Lee would have marched on toward Baltimore, knowing that Meade's army lay intrenched in his path. There is a homely maxim running to the effect that you can lead a horse to water, but cannot make him drink. The two generals, therefore, merely launched their columns out hit or miss, like men playing at blind-man's-buff.

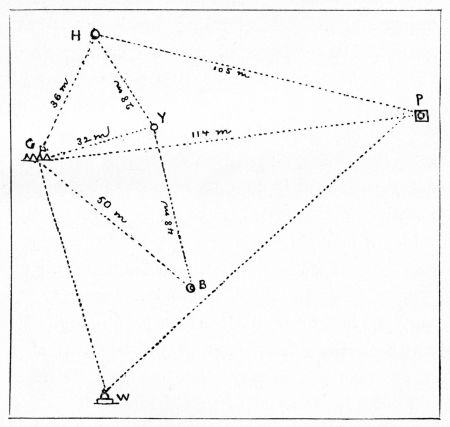

Gettysburg lies at the apex of a triangle of which Harrisburg and Baltimore form the base angles, at north and south—Harrisburg being only thirty-six and Baltimore about fifty miles distant. York and Carlisle also lie either on or so near this triangle as to come within its scope as a basis for military operations. Placed at Gettysburg, an army threatened all of these points.

Diagram showing strategic value of Gettysburg. H., Harrisburg; G., Gettysburg; P., Philadelphia; Y., York; B., Baltimore; W., Washington.

From a military point of view there are but two features about Gettysburg on which the eye would long rest. These are the two ridges, with a broad[15] valley between, heaved up at east and west and running off south of the town. They stand about a mile apart, though the distance is sometimes less than that. As it nears Gettysburg the easternmost ridge glides down, by[16] a gentle slope, into what may be called a plain, in comparison with the upheavals around it, although it is by no means a dead level. Yet it is open because the ridges themselves have stopped short here, forming headlands, so to speak, above the lower swells. On coming down off this ridge the descent is seen to be quite easy—in fact, two roads ascend it by so gradual a rise that the notion of its being either high or steep is quite lost, and you are ready to discard off-hand any preconceived notion about its being a natural stronghold. It is mostly on this slope that Gettysburg is built, its houses extending well up toward the brow, and its cemetery occupying the brow itself. Hence, although the centre of Gettysburg may be three-fourths of a mile from the cemetery gate, the town site is in fact but a lower swell of the historic ridge which has since taken the name of its graveyard—Cemetery Ridge.

Across this valley, again, the western ridge, which looks highest from the town, has what Cemetery Hill has not, namely, a thin fringe of[17] trees skirting its entire crest, thus effectually masking the view in that direction; and it is further distinguished by the cupola of the Lutheran Seminary,[4] seen rising above trees at a point opposite the town, and giving its name to this ridge—Seminary Ridge. Both ranges of heights are quite level at the top, and easily traversed; so also the slopes of both are everywhere easy of ascent, the ground between undulating, but nowhere, except far down the valley, badly cut up by ravines or watercourses. Indeed, better ground for a fair stand-up fight it would be hard to find; for all between the two ridges is so clear and open that neither army could stir out toward its opponent without being detected at once—the extreme southern part of the valley excepted. In this respect I take the liberty of observing that the actual state of things proved very different from that conveyed in some of the published accounts, wherein Cemetery Ridge is represented as a sort of Gibraltar.

A very brief survey, however, suggests that an army could be perfectly hid behind the trees of[18] Seminary Ridge, as well as better sheltered from artillery fire, while one stretched out along the bare and treeless summit of Cemetery Ridge would be without such screen or protection.

The description must be a little farther pursued, if the battle is to be at all intelligently followed.

Enough for the two main ridges enclosing Gettysburg and its valley. We come now to that most striking feature of the landscape, notably on the side of Cemetery Ridge, but more or less characteristic of both sides of the valley. This is the group of hills standing off from Cemetery Ridge at either end, just as if, at some remote time, this ridge had formed a continuous chain, the summits of which had been cleanly shaved off at the centre, leaving these isolated clusters to show where the wasting forces had passed. From different points of view we may see one or both of them rising above the ridge like giant watch-towers set at the extremities of some high embattled wall.

Let us first take the northernmost cluster, formed of Wolf's, McAllister's, and Culp's hills.[19] It is seen to be thrown back behind Cemetery Hill, to which Culp's Hill alone is slenderly attached by a low ridge, so making an elbow with it, or, in the military phrase, a refused line. Between Culp's Hill and Wolf's Hill flows Rock Creek, the shallow stream so often mentioned in connection with the battle, its course lying through a shaggy ravine.[5] The ravine and stream of Rock Creek threw Wolf's Hill somewhat out of the true line of defence, but the merest novice in military art sees at a glance why the possession of Culp's Hill was all-essential to the security of Cemetery Hill, since there is little use in shutting the front door if the back door is to be left standing open.

The same is just as true of the southernmost group, composed of Little and Great Round Tops, two exceedingly picturesque summits, standing up above the generally monotonous contours about them in strong relief. They also were wooded from base to summit, and they show, even more distinctly than the first group, where the crushing out or denuding forces[20] have been at work, in shelves or crevices of broken ledge at the highest points, in ugly bowlders cropping out on the slopes, in miry gullies crawling at their feet, but most of all in the deformed heap of ripped-up ledges, topped with coppices and scattered trees, thrust out from Little Round Top and known as the Devil's Den.[6]

When it is added that the way is open between the two Round Tops to the rear of Cemetery Ridge, the importance of holding them firmly becomes self-evident; and inasmuch as the greatest natural strength of this ridge lay at its extremities, or flanks, so its weakness would result from a neglect to occupy those flanks.

This line was assailable at one other point. As it approaches Little Round Top the ridge sinks away to the general level around it, or so as to break its continuity, thus leaving a gap more or less inviting the approach of an enemy. The whole extent of this crooked line, at which we have just glanced, is about two and a half miles.

Down below, in the valley, there is another swell of ground, hardly worth dignifying by the[21] name of ridge, yet assuming a certain importance, nevertheless, first because it starts from the town close under Cemetery Hill, thence crossing the valley diagonally till it becomes merged in Seminary Ridge, at a point nearly opposite to the Round Tops, and next because the Emmettsburg road runs on it. In brief, its relation to the battle was this: it ran from the Union right into the Confederate right, so traversing the entire front of both armies. It had an important part to play in the second day's battle, as we shall soon see, for, though occupying three days, Gettysburg was but a series of combats in which neither army employed its whole force at any one time.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Gettysburg is the county seat of Adams County; is one hundred and fourteen miles west of Philadelphia. Pennsylvania College is located here.

[2] The National Cemetery was dedicated by Abraham Lincoln, Nov. 19, 1863; it is a place of great and growing interest and beauty. The National Monument standing on this ground, where sleeps an army, was dedicated by General Meade in 1869. The monument itself was designed by J. G. Batterson, of Hartford, Conn., the statuary by Randolph Rogers. In 1872 the cemetery was transferred to the national government. A large part of the adjoining ridge is in charge of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, a corporation formed under the laws of Pennsylvania for the preservation of the field[22] and its landmarks. No other battle-ground was ever so distinctly marked or so easily traced as this.

[3] Shells remain sticking in the walls of some buildings yet. A memorial stone at the steps in front of the Lutheran church, on Chambersburg street, indicates the spot where Chaplain Howell, of the 90th Pennsylvania Volunteers, was shot dead while entering the church, then being used as a hospital.

[4] The Lutheran Seminary was used both as a hospital and observatory by the Confederates. Lee's headquarters were in a little stone house quite near the seminary buildings, which are not more than half a mile from the centre of Gettysburg.

[5] In 1863 all these hills were much more densely wooded than now, so forming an impenetrable screen to their defenders.

[6] The bowlder-strewn strip of ground lying between Devil's Den and Little Round Top is the most impressive part of the field, I think.

II

THE MARCH INTO PENNSYLVANIA

It is in no way essential to relate in detail how Lee's army, slipping away from ours on the Rappahannock,[7] and after brushing out of its path our troops posted in the Shenandoah Valley, had been crossing the Potomac into Maryland since the 21st of June, by way of the Cumberland Valley, without firing a shot.[8]

A very unusual thing in war it is to see an army which has just been acting strictly on the defensive suddenly elude its adversary for the purpose of carrying the war into that enemy's country! It marks a new epoch in the history of that war, and it supposes wholly altered conditions. In this particular instance Lee's moves were so bold as almost to savor of contempt.

It is enough to know that Lee was now in[24] Pennsylvania, at the head of seventy thousand men, before our army reached the Potomac in pursuit of him, if following at a respectful distance be called a pursuit.

At no period of the war, their own officers said, had the Confederates been so well equipped, so well clothed, so eager for a fight, or so confident of success; and we may add our own conclusions, that never before had this army taken the field so strong in numbers, or with such a powerful artillery.[9]

The infantry were armed with Enfield rifles, fresh from British workshops, and it is probable that no equal number of men ever knew how to use them better. Indeed, we consider it indisputable that the Confederates greatly excelled the Union soldiers as marksmen. Most of them were accustomed to the use of firearms from boyhood; in some sections they were noted for their skill with the rifle. The Confederates, therefore, were nearly always good shots before they went into the army, while the Union soldiers mostly had to acquire what skill they could after going into the ranks. In the[25] South the habit of carrying arms was almost universal: in the North it was not only unusual, but unpopular as well as unlawful.

Man for man, the Confederate cavalry was also superior to the Union horse, because in one section riding is a custom, in the other a pastime rarely indulged in. Consequently, it took months to teach a Union cavalryman how to ride,—a costly experiment when your adversary is already prepared,—whereas if there is anything a Southerner piques himself upon, it is his horsemanship.[10]

Lee's cavalry had preceded the infantry by nearly a week, reaching Chambersburg on the 16th, seizing horses and provisions for the use of the army behind them, and spreading consternation to the gates of Harrisburg itself. Having loaded themselves with plunder unopposed, they then fell back upon the main army, thus leaving it in some doubt whether this raid accomplished all it designed, or was only the prelude to something for which it was serving as a mask.[11]

All doubts were set at rest, however, when, on the 23d, Ewell's dust-begrimed infantry came tramping into Chambersburg, regiment after regiment, hour after hour, until the streets fairly swarmed with them. Though the houses were shut up, a few citizens were in the streets, or looking out of their windows at the passing show, as men might at the gathering of a storm-cloud about to burst with destructive fury upon them; and though the time was hardly one for merriment, we are assured that some of these lookers-on could not refrain from "pointing and laughing at Hood's ragged Jacks" as they marched along to the tune of "Dixie's Land." "This division," remarks the partial narrator, "well known for its fighting qualities, is composed of Texans, Alabamians, and Arkansians, and they certainly are a queer lot to look at. They carry less than any other troops; many of them have only got an old piece of carpet or rug as baggage; many have discarded their shoes in the mud; all are ragged and dirty, but full of good-humor and confidence in themselves and their general.[12] They answered the[27] numerous taunts of the Chambersburg ladies with cheers and laughter." To the scowling citizens the Confederates would call out from the ranks, "Well, Yank, how far to Harrisburg? How far to Baltimore? What's the charge at the Continental?" or some such innocuous bits of irony as came into heads turned, no doubt, at the thought of standing unchallenged on Northern soil, where nothing but themselves recalled war or its terrors, or at sight of the many evidences of comfort and thrift to which they themselves were strangers. But we shall meet these exultant ragamuffins ere long under far different circumstances.

This was Lee's corps of observation, destined to do most of the hard marching and fighting which usually falls to the lot of the cavalry, as it was mostly composed of old, well-seasoned soldiers, who had been accustomed, under the lead of Jackson, to win their victories largely with their legs. Part marched through the town, and went into camp on the Carlisle road, part occupied the pike leading toward Gettysburg; sentries were posted in the streets, a military commandant was appointed, and for the time being Chambersburg[28] fell wholly under rebel rule, which, so long as it remained the army headquarters, we are bound to say does not appear to have been more onerous than circumstances would warrant.

Ewell's corps was followed, at one day's march, by the main body, comprising Hill's and Longstreet's corps, with whom marched Lee himself, the man on whom all eyes, North and South, were now turned.

As soon as the main body had come up Ewell moved straight on toward Carlisle and Harrisburg with two divisions, while his third turned off to the east, toward York, with the view of drawing attention away from the main object by seeming to threaten Baltimore or Philadelphia.[13] It was to strike the Susquehanna at Columbia, and get possession of the railway bridge there, as a means of passing over to the north side of that river to Harrisburg.

This division (Early's) passed through Gettysburg on the 26th,[14] reaching York the next day. On the 28th his advance arrived at the Susquehanna too late to save the railway bridge from the flames.[15] On this same day[29] Ewell's advance encamped within four miles of Harrisburg, where some skirmishing took place.

Here, then, was Lee firmly installed within striking distance of the capital of the great Keystone State, and by no means at so great a distance from Philadelphia or Washington as not to make his presence felt in both cities at once.

If he had not come prepared to fight every soldier that the Federal government could bring against him—to fight even against odds—what was he doing here in the heart of Pennsylvania?

The army which followed Lee into Pennsylvania was brave and devoted—none more so. It looked up to him with a species of adoration, born of an abiding faith in his genius. Reasoning from experience, the belief that it would continue to beat the Union army was not unfounded. At any rate, it was universal. Thus led, and imbued with such a spirit, no wonder the Confederate army considered itself invincible.

Thus followed, Lee, or Uncle Robert, as he was familiarly called by his soldiers, though no man[30] could be more aristocratic in his tastes or manners, was accustomed to exact greater efforts from them, both in marching and fighting, than the Union generals ordinarily could from their better-fed, better-clothed, and better-disciplined troops.

A pen portrait of General Lee himself, as he appeared at this time, seems necessary to the historical completeness of this sketch. It is drawn by a British colonel,[16] on leave with Lee's army, where he found himself quite at home. He says: "General Lee is, almost without exception, the handsomest man of his age I ever saw. He is fifty-six years old, tall, broad-shouldered, very well made, well set up—a thorough soldier in appearance; and his manners are courteous and full of dignity. He generally wears a well-worn long gray jacket, a high black felt hat, and blue trousers tucked into his Wellington boots. I never saw him carry arms, and the only marks of military rank are the three stars on his collar. He rides a handsome horse which is extremely well groomed. He himself is very neat in his dress and person, and in the most arduous marches, as after the retreat from Gettysburg,[31] when everybody else looked and was extremely dirty, he always looked smart and clean."

Positions, June 28th.

In an order commending the behavior of his men while on the march, Lee called attention to certain excesses which he declared his intention of repressing in a summary manner.

The region to which the Confederate operations were now confined is indicated by the accompanying[32] map. It will be seen that Lee had not hesitated to scatter his army considerably.

Leaving Ewell before Harrisburg, Early at York, and Lee himself at Chambersburg, we will look first at the state of feeling brought about by this daring invasion, which had been urged from Richmond on the theory that the road to peace lay through Pennsylvania, via Washington.

FOOTNOTES:

[7] He withdrew two corps, by his left, to Culpepper, leaving one in the trenches of Fredericksburg. Had this corps been crushed while thus isolated, as it ought, Lee's invasion must have ended then and there.

[8] A glance at the map shows how the northerly bend of the Potomac facilitated an invasion by this route. The outposts at Harper's Ferry and Winchester having been forced, there was nothing to stop the enemy's advance.

[9] The Confederate army comprised three infantry corps, and one of cavalry. Each corps had three divisions, each division averaged a little over four brigades, of which there were thirty-seven present at Gettysburg. The British Colonel Freemantle, who accompanied Lee's army, puts the strength of these brigades at two thousand eight hundred men each. The relative strength of the army corps was more nearly equal than in those of the Union army. The Confederates brought with them two hundred and seventy pieces of artillery.

[10] The main body, under Stuart, had gone around the rear of the Union army, by Lee's permission, in the expectation of harassing it while on the march, and of then rejoining Ewell, on the Susquehanna. It failed to do either, and many attribute all of Lee's misfortunes in this campaign to the absence of Stuart.

[11] Jenkins, who commanded, was paid in his own coin at Chambersburg, by the proffer of Confederate scrip in payment for some alleged stolen horses. He himself had been professedly paying for certain seized property in this same worthless scrip.

[12] Contrast this with the generous, even prodigal, way the Union soldiers were provided for, and who can doubt the devotion of these ragged Confederates to their cause?

[13] So long as this division remained at York, the question as to where Lee meant to concentrate would be still further confused. See diagram.

[14] Early levied a contribution on the borough, which the town council evaded by pleading poverty.

[15] A small Union force which had been holding the bridge set it on fire on the approach of the Confederates.

[16] This was Colonel Freemantle, who has a good word for everything Confederate. On being courteously received within the Union lines after Gettysburg, he was much surprised to find that the officers were gentlemen.

III

FIRST EFFECTS OF THE INVASION

Meantime, from before and behind the Confederate columns, two streams flowed out of the doomed valley: one to the north, an army of fugitives hurrying their flocks, herds, and household goods out of the enemy's reach; the other carrying off to Virginia the plunder of towns and villages.

As the swarm of fugitives made straight for Harrisburg, it was but natural that the inpouring of such panic-stricken throngs, all declaring that the enemy was close behind them, should throw that city into the wildest commotion, which every hour tended to increase. We will let an eye-witness describe the events of a single day.

"The morning broke upon a populace all astir, who had been called out of bed by the beat of the alarming drum, the blast of the bugle, and[35] the clanging of bells. The streets were lively with men, who were either returning from a night's work on the fortifications or going over to relieve those who were toiling there. As the sun rose higher the excitement gathered head. All along the streets were omnibuses, wagons, and wheelbarrows, taking in trunks and valuables and rushing them down to the dépôt to be shipped out of rebel range. The stores, the female seminaries, and almost every private residence were busy all of the forenoon in swelling the mountain of freight that lay at the dépôt. Every horse was impressed into service and every porter groaned beneath his burdens.

"The scene at the dépôts was indescribable, if not disgraceful. A sweltering mass of humanity thronged the platforms, all furious to escape from the doomed city. At the bridge and across the river the scene was equally exciting. All through the day a steady stream of people, on foot and in wagons, young and old, black and white, was pouring across it from the Cumberland Valley, bearing with them their household goods and live-stock. Endless trains, laden[36] with flour, grain, and merchandise, hourly emerged from the valley and thundered across the bridge and through the city. Miles of retreating baggage-wagons, filled with calves and sheep tied together, and great, old-fashioned furnace-wagons loaded with tons of trunks and boxes, defiled in continuous procession down the 'pike and across the river, raising a dust as far as the eye could see."

It may be added that the records of the State and the money in the bank-vaults were also removed to places of safety, and the construction of defensive works was begun, as much, perhaps, with the purpose of allaying the popular excitement as from any hope of holding the city against Lee, since Harrisburg was in no condition either to stand a siege or repel an assault at this time.

The wave of invasion made itself felt even as far as Pittsburg on the one side and Baltimore on the other.[17] Governor Curtin promptly called on the people of Pennsylvania to arm and repel the invader. Yet neither the imminence of the danger nor the stirring appeal of the executive of the[37] State could arouse them at first. In the emergency the neighboring States were appealed to for help. In response the militia of those States were soon hastening toward the threatened points[18] by every available route; yet it was only too evident that raw soldiers, no matter how zealous or patriotic, would prove little hinderance to Lee's marching where he would, or long dispute with his veterans the possession of Harrisburg were it once seriously attacked.

But where was the army of the Potomac all this time—the army whose special task it was to stand between this invader and his prey? Must unarmed citizens be called upon to arise and defend their homes when a hundred thousand veterans were in the field?

For more than a week Lee had thus been laying waste a most rich and fertile section of Pennsylvania at his leisure. Practically, indeed, the whole State was in his grasp. Would Harrisburg or Philadelphia be the first fruits of his audacity? The prize was indeed tempting, the way open. The only real impediment was the[38] Army of the Potomac, and Lee, too, was now anxiously asking himself what had become of that army.[19] He had foreseen that it must follow him up; that every effort would be bent to compass his destruction; and it was a foregone conclusion that he must fight somewhere, if there was either enterprise or courage left on the Union side. He had even calculated on drawing the Union army so far away from fortified places that its defeat would ensure the fall of Baltimore and Washington. But as regarding its whereabouts at the present moment, Lee was completely in the dark. In an evil hour he had allowed the bulk of his cavalry to run off on a wild-goose chase around the rear of the Federal army, so that now, in his hour of need, though without his knowing it, the whole Federal army interposed to prevent its return.[20] It is quite true that up to this time Stuart, who led this cavalry, had given so many signal proofs of his dexterity that Lee was perhaps justified in inferring that if he heard nothing from Stuart, it was because the Union army was still in Virginia. And in that belief he was acting.

Moreover, instead of being among a population eager to give him every scrap of information, Lee was now among one where every man, woman, and child was a spy on his own movements. In the absence, then, of definite knowledge touching the Union army, he decided to march on Harrisburg with his whole force, and issued orders accordingly.

When there was no longer a shadow of doubt that Lee's whole army was on the march up the Cumberland Valley, sweeping that valley clean as it went, the Union army also crossed the Potomac, on the 25th and 26th of June, and at once began moving up east of South Mountain, so as to discharge the double duty laid upon it all along of keeping between the enemy and Washington, while at the same time feeling for him through the gaps of South Mountain as it marched. For this task the Union general kept his cavalry well in hand, instead of letting it roam about at will in quest of adventures.

This order of march threw the left wing out as far as Boonsborough and Middletown, with[40] Buford's cavalry division watching the passes by which the enemy would have to defile, should he think of making an attack from that flank.[21] The rest of the army was halted, for the moment, around Frederick. The plan of operations, as first fixed, did not lack in boldness or originality. It was to follow Lee up the Cumberland Valley with two corps, numbering twenty thousand men, while the rest of the army should continue its march toward the enemy on the east side of South Mountain, but within supporting distance. As this would be doing just what Lee[22] had most reason to dread, it would seem most in accordance with the rules of war. At any rate, it initiated a vigorously aggressive campaign.

At this critical moment the Union army was, most unexpectedly, deprived of its head.

In its pursuit of Lee this army had been much hampered by divided counsels, when, if ever united counsels were imperatively called for, now was the time. Worse still, it had too many commanders, both civil and military. The President, the Cabinet, the General-in-Chief (Halleck), and[41] even some others, in addition to the actual commander, not to speak of the newspapers, had all taken turns in advising or suggesting what should, or what should not, be done. United action, sincere and generous co-operation, as between government and army, were therefore unattainable here. The government did not trust its general: the general respected the generalship of the Cabinet most when it was silent. Nobody in authority seemed willing to grant Hooker what he asked for, let it be ever so reasonable, or permit him to carry out his own plans unobstructed, were they ever so promising or brilliant. He could not get the fifteen or twenty thousand soldiers who were then dawdling about the camps at Baltimore, Washington, and Alexandria. He was brusquely snubbed when he asked for leave to break up the post at Harper's Ferry, when by doing so ten thousand good troops would have been freed to act against the enemy's line of retreat.

Harmony being impossible, Lee seemed likely to triumph through the dissensions of his enemies.

Mortified at finding himself thus distrusted and[42] overruled, Hooker threw up the command on the 27th, and on the 28th General Meade succeeded him. So suddenly was the change brought about, that when the officer bearing the order awakened Meade out of a sound sleep at midnight, he thought he was being put in arrest.

It is asserted by those who had the best means of knowing—indeed, it is difficult to see how it could be otherwise—that the army had lost faith in Hooker, and that the men were asking of each other, "Are we going to have another Chancellorsville?" Be that as it may, there were few better soldiers in that army than Meade; none, perhaps, so capable of uniting it at this particular juncture, when unity was so all-important and yet so lamentably deficient. This was the third general the army had known within six months, and the seventh since its formation. It was truly the graveyard of generals; and each of the disgraced commanders had his following. If, under these conditions, the Army of the Potomac could still maintain its efficiency unimpaired, it must have been made of different stuff from most armies.

It was not that the Union soldiers feared to meet Lee's veterans. Lee might beat the generals, but the soldiers—never! Yet it can hardly be doubted that repeated defeat had more or less unsettled their faith in their leaders, if not in themselves; since even the gods themselves struggle in vain against stupidity.[23]

If the new appointment did not silence all jealousies among the generals, or infuse great enthusiasm into the rank and file,—and we are bound to admit that Meade's was not a name to conjure with,—it is difficult to see how a better selection could have been made, all things considered. In point of fact, there was no one of commanding ability to appoint; but every man in the army felt that Meade would do his best, and that Meade at his best would not fall far behind the best in the field.

Meade could not become the idol of his soldiers, like Lee, because he was not gifted by nature with that personal magnetism which attracts men without their knowing why; but he could and did command unhesitating obedience and respect.

In point of discipline, however, the Union army[44] was vastly the superior of its adversary, and that counts for much; and in spite of some friction here and there, like a well-oiled machine the army was now again in motion, with a cool head and steady hand to guide it on. But as no machine is stronger than its weakest part, it remained to be seen how this one would bear the strain.

Thus a triumphant and advancing enemy was being followed by a beaten and not over-confident one, its wounds scarcely healed,[24] not much stronger than its opponent, and led by a general new to his place, against the greatest captain of the Confederacy. How could the situation fail to impose caution upon a general so fully and so recently impressed with the consequences of taking a false step? Meade's every move shows that from the beginning this thought was uppermost in his mind.

With the effects of Lee's simple presence thus laid before us, it is entirely safe to ask what should have stopped this general from dictating his own terms of peace, either in Philadelphia or Baltimore, provided he could first beat the Union army in Pennsylvania?

FOOTNOTES:

[17] At Pittsburg defensive works were begun. In Philadelphia all business was suspended, and work vigorously pushed on the fortifications begun in the suburbs. At Baltimore the impression prevailed that Lee was marching on that city. The alarm bells were rung, and the greatest consternation prevailed.

[18] A great lukewarmness in the action of the people of Pennsylvania is testified to on all sides. See Professor Jacobs' "Rebel Invasion," etc. About sixteen thousand men of the New York State militia were sent to Harrisburg between the 16th of June and the 3d of July; also several thousand from New Jersey (but ordered home on the 22d). General Couch was put in command of the defences of Harrisburg.

[19] Hooker would not cross the Potomac until assured that Lee's whole army was across. He kept the Blue Ridge between himself and Lee in obedience to his orders to keep Washington covered.

[20] The presence of Lee's cavalry would have allowed greater latitude to his operations, distressed the Pennsylvanians more, and enabled Lee to select his own fighting-ground.

[21] So long as these passes were securely held, Lee would be shut up in his valley.

[22] Open to serious objections; but then, so are all plans. Tied down by his orders, Hooker would have taken some risks for the sake of some great gains. By closing every avenue of escape, it would have ensured Lee's utter ruin, provided he could have been as badly beaten as at Gettysburg.

[23] This feeling was so well understood at Washington that a report was spread among the soldiers that McClellan, their old commander, was again leading them, and the report certainly served its purpose.

[24] The army was not up to its highest point of efficiency. It had just lost fifty-eight regiments by expiration of service. This circumstance was known to Lee. The proportion of veterans was not so great as in the Confederate army, or the character of the new enlistments as high as in 1861 and 1862.

IV

REYNOLDS

The problem presented to Meade's mind, on taking command, was this: What are the enemy's plans, and where shall I strike him? He knew that part of Lee's army was at Chambersburg, part at Carlisle, and part at York. Was it Lee's purpose to concentrate his army upon the detachment at York or upon that at Carlisle, or would he draw these two detachments back into the Cumberland Valley, there to play a merely defensive game? Should the junction be at Carlisle, it would mean an attack on Harrisburg: if at York, or at some point between the main body and York, it would indicate an advance in force toward Philadelphia, Baltimore, or Washington. As all these things were possible, all must be duly weighed and guarded against. With a wily, brave, and confident enemy before him, Meade did not[47] find himself on a bed of roses, truly; and he may well be pardoned the remark attributed to him when ordered to take the command, that he was being led to execution.

Meade needed no soothsayer to tell him that if Lee crossed the mountains, it would be because he meant to fight his way toward his object through every obstacle.

What was that object?

In answering this question the political considerations must be first weighed. In short, the purpose—the great purpose—of the invasion must be penetrated. That being done, the military problem would easily solve itself.

It was not to be supposed that Lee had invaded Pennsylvania solely for the purpose of taking a few small towns, or even a large one, like Harrisburg, or of filling up his depleted magazines. He was evidently after larger game. His ultimate aim, clearly, was to capture Washington, as a signal defeat of the Union army would easily enable him to do. It would crown the campaign brilliantly, would fulfil the hopes, and beyond doubt or cavil ensure the triumph, of the Confederacy.[48] It is true that Meade's orders held him down to a defence of the national capital first and foremost; in no sense, then, was he the master of his own acts: yet he showed none the less sagacity, we think, in concluding that Lee would presently be found on the east side of the mountains, and in preparing to meet him there, not astride the mountains as Hooker had proposed doing, but with his whole army more within his reach. Meade was prudent. He would err, if at all, on that side; yet the result vindicated his judgment sooner than was thought for.

This being settled, there still remained the question of relieving Pennsylvania. The enemy's presence there was an indignity keenly enough felt on all sides, but to none was it such a home-thrust as to the Pennsylvanians in the Union army, at the head of whom was Meade himself.[25]

Though Hooker's plan promised excellent results here, Meade was fearful lest Lee should cross the Susquehanna, and take Harrisburg before he could be stopped. To prevent this the army must be pushed forward. Meade, therefore, at once drew back[49] the left wing toward Frederick, thus giving up that plan in favor of one which he himself had formed; namely, of throwing the army out more to the northeast, the better to cover Baltimore from attack, should that be Lee's purpose, as Meade more than suspected. Selecting Westminster, therefore, as his base from this time forth, and the line of Big Pipe Creek, a little to the north of that place, as his battle-ground, Meade now set most of the army in motion in that direction, leaving Frederick to the protection of a rear-guard.

The army now marched with its left wing thrown forward toward South Mountain, Buford's cavalry toward Fairfield, to clear that flank, the First and Eleventh Corps toward Emmettsburg, the Third and Twelfth toward Middleburg, the Fifth to Taneytown, the Second to Uniontown, and the Sixth, on the extreme right, to New Windsor.

Two other divisions of Union cavalry, Kilpatrick's and Gregg's, marched one on the right flank, the other in front, with orders to keep the front and flanks of the army well scouted and protected.

It will be seen from this order of march that, in proportion as they went forward, Buford's cavalry, with the three infantry corps forming the left wing, were approaching the enemy's main body at Chambersburg. South Mountain was, therefore, the wall behind which the two contending armies were playing at hide-and-seek.[26]

Lee had only just given orders for his whole force to move on Harrisburg, when, late in the night of the 28th, a scout brought news to him of the Union army being across the Potomac, and on the march toward South Mountain.[27] This report could not fail to throw the Confederate headquarters into a fever of excitement, ignorant to that hour of that army's being across the Potomac. The mystery was cleared up at last. In a moment the plan of campaign was changed.[28] Lee soon said to some of the officers about him, "To-morrow, gentlemen, we will not move to Harrisburg as we expected, but will go over to Gettysburg and see what General Meade is about."

By placing himself on the direct road to Baltimore, Lee's purpose of first drawing the Union[51] army away from his line of retreat, and of then assailing it on its own, stands fully revealed. The previous orders were therefore countermanded on the spot. Hill and Longstreet were ordered from Chambersburg to Gettysburg,[29] Ewell was called back from Carlisle, and Early from York.

If Meade had known Lee's whereabouts, it is safe to assume that the Union army would have been massed toward its left rather than its right; and if Lee had been correctly informed on his part, it is unlikely that he would have risked throwing his columns out at random against the Union army, as he was now doing. Only the fatuity of the Union generals saved Lee's vanguard on the 1st of July. Yet he held the very important advantage of having already begun the concentration of his army—an easy thing for him to do, inasmuch as but one of his three corps was separated from the others—before Meade discovered by chance what was so near proving his ruin. One day's march would bring all three up within supporting distances, two in position for giving battle.

Heth's division of Hill's Corps got as far as Cashtown, eight miles from Gettysburg, on the 29th; Rodes' division of Ewell's Corps was coming down by the direct road from Carlisle, east of South Mountain; Early's division of this corps began its march back from York to Gettysburg on the morning of the 30th. These three divisions, or one-third of Lee's whole army, therefore, formed the enemy's vanguard which would first strike an approaching force. But, as we have seen, the whole army was in march behind it, and by the next day well closed up on the advance.

Leaving them to pursue their march, which was by no means hurried, let us, to borrow Lee's very expressive phrase, "see what General Meade was about."

On the 29th all seven of the Union corps were advancing northward like fingers spread apart, and exactly in an inverse order from Lee's three, which were converging on the palm of the hand. On the 30th this divergent order of march continued to conduct the corps still farther apart, with the result also,[53] considering Gettysburg as the ultimate point of concentration, that the bulk of the army was away off to the right of Gettysburg.[30] Moreover, Meade's efforts to get the army up to this position, or in front of his chosen line of defence on Pipe Creek, had covered the roads with stragglers, and compelled at least one corps to halt for nearly a whole day.[31]

It was not until nightfall of the 30th, or forty-eight hours after it was begun, that Meade knew of the enemy's movement toward Gettysburg; and even then he did not feel at all sure of having detected the true point of concentration. Indeed, his want of accurate information on this head seems surprising. By that time his own army was stretched out from Emmettsburg, on the northwest, to Manchester at the east, thus putting it out of Meade's power to concentrate it at Gettysburg in one day. By endeavoring to cover too much ground his army had been dangerously scattered. Even without cavalry Lee had fairly stolen a march on him. And it is not improbable that Hooker might now have been "shocked," in his turn.[32]

Our present business is now wholly with the left wing of the Union army,—its right being quite out of reach—that is to say, with the three infantry and one cavalry corps commanded by that thorough soldier, so beloved by the whole army, General Reynolds, the actual chief of the First Corps.

Buford had spent the 29th in scouring the passes of South Mountain as far north as Monterey, without getting sight of the enemy, however, until he halted for the night at Fountaindale, when he then perceived the camp-fires of a numerous body of troops stretching along in his front and lighting up the road toward Gettysburg. Evidently they had just crossed South Mountain from the valley.

To Buford this sight was indeed as a ray of light in a dark place. No friendly force could be in that quarter. He determined to know who and what it was without loss of time. Before dawn his troopers were again in the saddle. They soon fell in with a strong column of infantry moving toward Gettysburg on the Fairfield (Hagerstown) road. After exchanging a[55] few shots, and having learned what he wanted to know, Buford hastened back to Reynolds, at Emmettsburg, with the news.

Reynolds immediately sent Buford back to Gettysburg, in order, if possible, to head off the enemy before he should reach that place, for which he was evidently making. A courier was also despatched to headquarters. This was the first trustworthy intelligence of Lee's movement to the east that Meade had thus far received. Could the enemy be massing on his left? It certainly looked like it. After this night there was only one word on the tongues of all men in that army—Gettysburg! Gettysburg!

The First Corps, also marching for Gettysburg, went into camp some five miles short of that town; the Eleventh lay at Emmettsburg; the Third at Taneytown. It is with them alone that we shall have to deal in what follows.

Positions, June 30th.

We have already seen that Meade had not designed advancing one step farther than might be found effectual for turning Lee back from overrunning the State. This was the first great[56] object to be attained. And this had now been done. To avoid being struck from behind, Lee had been forced to halt, face about, and look for a place to fight in. When the enemy should be fairly in motion southward, Meade meant[57] to take up the position along Pipe Creek, and await an attack there. But he no longer had the disposing of events. In order to gain this position now, Reynolds must have fallen back one or two marches; nor could Meade know that Lee was then coming half way to meet him; or that—strange confusion of ideas!—Lee had promised his generals not to fight a pitched battle except on ground of his own choosing; certainly not on one his adversary had chosen for him; least of all where defeat would carry down with it the cause of the Southern Confederacy itself.

Reynolds, therefore, held the destinies of both armies in his keeping on that memorable last night of June. He now knew that any further advance on his part would probably result in bringing on a combat—a combat, moreover, in which both armies might become involved, for his military instinct truly foreshadowed what was coming. There was still time to fall back on the main army, to avoid an engagement. But Reynolds was not that kind of general. He was the man of all others to whom the whole[58] army had looked in the event of Hooker's incapacity from any cause, as well as the first whom the President had designed to replace him. He now shared Meade's confidence to the fullest extent. He was a soldier of the finest temper, a Pennsylvanian, like Meade himself, neither rash on the one hand, nor weighed down by the feeling that he or his soldiers were overmatched in any respect on the other. To him, at least, Lee was no bugbear. Having come there expressly to find the enemy, he was not going to turn his back now that the enemy was found. Reynolds was, therefore, emphatically the man for the hour. He knew that Meade would support him to the last man and the last cartridge. He fall back? There was no such word in Reynolds' vocabulary. His order was "Forward!"

So history has indissolubly linked together the names of Reynolds and of Gettysburg, for had he decided differently there would have been no battle of Gettysburg.

Thus it was that all through the silent watches of that moonlit summer's night the roads leading to Gettysburg from north and south, from east[59] and west, were lighted up by a thousand camp-fires. Without knowing it, the citizens of that peaceful village were sleeping on a volcano.

FOOTNOTES:

[25] Besides Meade, there were Hancock, Reynolds, and Humphreys—a triumvirate of some power with that army. Pennsylvania had also seventy-three regiments and five batteries with Meade.

[26] While thus feeling for Lee along the mountain passes with his left hand, Meade was reaching out the right as far as possible toward the Susquehanna, or toward Early at York.

[27] This was Longstreet's scout, Harrison. "He said there were three corps near Frederick when he passed there, one to the right and one to the left; but he did not succeed in getting the position of the other."—Longstreet.

[28] This shows how little foundation exists for the statements of the Comte de Paris and others that Hooker's strategy compelled Lee to cross the mountain, when it is clear that he knew nothing whatever of Hooker's intentions. This is concurred in by both Lee and Longstreet. Moreover, Hooker had scarcely put his strategy in effect when he was relieved.

[29] In point of fact, the concentration was first ordered for Cashtown, "at the eastern base of the mountain."—Lee. Ewell and Hill took the responsibility of going on to Gettysburg, after hearing that the Union cavalry had been seen there.

[30] On the night of June 30th, Meade's headquarters and the artillery reserve were at Taneytown, the First Corps at Marsh Run, Eleventh at Emmettsburg, Third at Bridgeport, Twelfth at Littlestown, Second at Uniontown, Fifth at Union Mills, Sixth and Gregg's Cavalry at Manchester, Kilpatrick's at Hanover—a line over thirty miles long.

[31] By being compelled to ford streams without taking off shoes or stockings, the men's feet were badly blistered.

[32] Upon taking command, Meade is said to have expressed himself as "shocked" at the scattered condition of the army.

V

THE FIRST OF JULY

Since early in the afternoon of June 30th, the inhabitants of Gettysburg had seen pouring through their village, taking position on the heights that dominate it, and spreading themselves out over all the roads leading into it from the west and north, squadron after squadron of horse, dusty and travel-stained, but alert, vigilant, and full of ardor at the prospect of coming to blows with the enemy at last.

This was a portion of that splendid cavalry which, under the lead of Pleasonton, Buford, Gregg, and Kilpatrick, at last disputed the boasted superiority of Stuart's famous troopers. At last the Union army had a cavalry force. These men formed the van of that army which was pursuing Lee by forced marches for the purpose of bringing him to battle.

Forewarned that he must look for the enemy to make his appearance on the Chambersburg and Carlisle roads,[33] and feeling that there was warm work ahead, Buford was keeping a good lookout in both directions. To that end he had now taken post on a commanding ridge over which these roads passed first to Seminary Ridge, and so back into Gettysburg. First causing his troopers to dismount, he formed them across the two roads in question in skirmishing order, threw out his vedettes, planted his horse-artillery, and with the little valley of Willoughby Run before him, the Seminary and Gettysburg behind him, and the First Corps in bivouac only five miles away toward Emmettsburg, this intrepid soldier calmly awaited the coming of the storm, conscious that if Gettysburg was to be defended at all it must be from these heights.

A pretty little valley was this of Willoughby Run, with its green banks and clear-flowing waters, its tall woods and tangled shrubbery, so soon to be torn and defaced by shot and shell, so soon deformed by drifting smoke and the loud cries of the combatants.

The night passed off quietly. Nevertheless, some thirty thousand Confederates, of all arms, were lying in camp within a radius of eight miles from Gettysburg. Their vanguard had discovered the presence of our cavalry,[34] and was waiting for the morning only to brush it away.

Next morning Heth's division was marching down the Chambersburg pike, looking for this cavalry, when its advance fell in with Buford's vedettes. While they halted to reconnoitre, these vedettes came back with the news that the enemy was advancing in force, infantry and artillery filling the road as far as could be seen. Warned that not a moment was to be lost, Buford at once sent off word to Reynolds, who, after ordering the First Corps under arms, and sending back for the Eleventh, himself set off at a gallop for Gettysburg, followed only by his staff.

Buford's bold front had thus caused the enemy to come to a halt; but soon after nine, supposing he had to do with cavalry alone, Heth deployed his skirmishers across the pike, forming his two leading brigades at each side[63] of it; these troops then pushed forward, and soon the crack of a musket announced that the battle of Gettysburg had begun.

After an hour's stubborn fighting, Buford was being slowly but surely pushed back over the first ridge, when a column of the Union infantry was seen coming up the Emmettsburg road at the double-quick. It was Wadsworth's division arriving in the nick of time, as the enemy's skirmishers, followed by Archer's brigade, were, even then, in the act of fording the run unopposed, and unless promptly stopped would soon be in possession of the first range of heights. It was really a neck-and-neck race to see who would get there first.

Reynolds was impatiently awaiting the arrival of his troops, who were making across the fields for the ridge he was so desirous of holding on the run. It was plain as day that he had determined to contest the enemy's possession of Gettysburg here. Cutler's brigade was the first to arrive. Hurrying this off to the right of the pike, where it formed along the crest of the ridge under a shower of balls,[64] Reynolds ordered the next, as it came up, to charge on over the ridge in its front, and drive Archer's men out of a wood that rose before him crowning the crest and running down the opposite slopes. It was done in the most gallant manner, each regiment in turn breaking off from the line of march to join in the charge under the eye of Reynolds himself, who, heedless of everything except the supreme importance of securing the position, rode on after the leading regiment into the fire where bullets were flying thickest. Not only was the enemy driven out of the wood, but back across the run, with the loss of about half the brigade, including Archer himself. At the very moment success had crowned his first effort, Reynolds fell dead with a bullet in his brain.[35]

Nothing could have been more unfortunate at this time. With Reynolds fell the whole inspiration of the battle of Gettysburg, but, worst of all, with his fall both the directing mind and that unquestioned authority so essential to bring the battle to a successful issue vanished from the field. He had been struck[65] down too suddenly even to transmit his views to a subordinate. Disaster was in the air.

This dearly bought success on the left was more than offset by what was going on at the right, where Davis' Confederate brigade, after getting round Cutler's flank, was driving all before it. Cutler had to fall back to the Seminary Ridge in disorder.

Having so easily cleared this part of the line, Davis' men next threw themselves astride the ridge, and seeing nothing before them but Hall's battery, which was then firing down the Chambersburg pike, they came booming down upon the guns, yelling like so many Comanche Indians. Before the battery could be limbered up the enemy were among the guns, shooting the cannoneers and bayoneting the horses. It was finally got off with the loss of one of the pieces.[36]

This success put the enemy in possession of all the Union line as far down as the pike, and threatened that part just won with a like fate. We had routed the enemy on the left, and been routed on the right.

Fortunately, the Sixth Wisconsin had been left in reserve near the Seminary a little earlier, and it was now ordered to the rescue. Colonel Dawes led his men up on the run. This regiment, with two of Cutler's that had turned back on seeing the diversion making in their favor, drove the enemy back again, up the ridge, to where it is crossed by a railroad cut, some two hundred yards north of the pike. To escape this attack most of them jumped down into the cut; but as the banks are high and steep and the outlet narrow, this was only getting out of the frying-pan into the fire, since while one body of pursuers was firing down into them from above, still another had thrown itself across the outlet and was raking the cut from end to end. This proved more than even Davis' Mississippians could stand, and though they fought obstinately enough, all were either killed, taken, or dispersed.

Heth's two attacking brigades having thus been practically used up after a fierce conflict, not with cavalry alone, with whom they had expected to have a little fun, but with infantry, in whom they[67] recognized their old antagonists of many a hard-fought field, and who fought to-day with a determination unusual even to them, Heth hesitated about advancing to the attack again in the face of such a check as he had just received, without strong backing up; but sending word of his encounter to Lee, he set about forming the fragments of the two defeated brigades on two fresh ones, where they could be sheltered from the Union fire.

Yet Hill, his immediate chief, had told him only the night before there was no objection in the world to his going into Gettysburg the next day.

This success also enabled Doubleday[37] to reform his line in its old position. The troops on the left had not been shaken, and Cutler's men were now coming back to the front eager to wipe out the disgrace of their defeat.

If the enemy's van had not been without cavalry to clear its march, Heth must inevitably have got into Gettysburg first. As it was, the unexpected resistance he had met with made Heth cautious. Lee's orders to his lieutenants were not to force[68] the fighting until the whole army should be up. Pender was therefore forming behind Heth, the artillery set at work, and all were impatiently looking out for Rodes' appearance on the Carlisle (or Mummasburg) road, before renewing the action.

This proved a most fortunate respite to the small Union force on Oak Ridge, as, in consequence of it,—the state of things just pointed out,—some hours elapsed before there was any more fighting by the infantry, though the artillery kept up its annoying fire. Meanwhile the two remaining divisions of the First Corps came on the ground. Robinson's was left in reserve at the Seminary, with orders to throw up some breastworks there; Doubleday's, now Rowley's, went into line partly to the right and partly to the left of the troops already there, thus extending both flanks considerably; and at the extreme left, which was held by Biddle's brigade, two companies of the Twentieth New York were even thrown out across the run, into the Harman house and out-buildings, where they did good service in keeping down the enemy's skirmish fire.[38]

Meantime, also, Pender's division had got into line. When formed for the attack it considerably outflanked the Union left. And a little later Rodes was seen coming down the Mummasburg road, or out quite beyond the right of the First Corps. Clearly, the combat just closed was child's play in comparison with what was about to begin.

These troops gave notice that they were shortly coming into action by opening a sharp cannonade from Oak Hill, the commanding eminence situated just beyond and in fact forming a continuation of Oak Ridge, where the First Corps stood, though separated from it somewhat.

This artillery fire from Oak Hill enfiladed the Union position so completely that nothing was left for the right but to fall back to Seminary Ridge, so as to show a new front to this attack. The centre and left, however, kept its former position, with some rearrangement of the line here and there, which had now become a very crooked one.

Twenty odd thousand men were thus waiting[70] for the word to rush upon between ten and eleven thousand.

Before the battle could be renewed, however, the Eleventh Union Corps came up through Gettysburg.[39] Howard, its actual head, was now in chief command of the field, as next in rank to Reynolds. He sent forward Schurz's and Barlow's divisions of this corps to confront Rodes, leaving Steinwehr's in reserve on Cemetery Hill.

Having preceded his corps to the field, Howard had already notified Meade, too hastily by half, that Reynolds was killed and the First Corps routed—a report only half true, and calculated to do much mischief, as it soon spread throughout the entire army. He also sent off an urgent request to Slocum, who was halted in front of Two Taverns, not five miles off, to come to his assistance with the Twelfth Corps.

Supposing the day lost from the tenor of Howard's despatch, lacking perhaps the fullest confidence in that general's ability and experience, and thinking only of how he should save what was left, Meade forthwith posted Hancock[71] off to Gettysburg, with full authority to take command of all the troops he might find there, decide whether Gettysburg should be held or given up, and to promptly report his decision, to the end that proper steps might be taken to counteract this disaster if yet possible.

Slocum would not stir from Two Taverns without orders, though it is said the firing was distinctly heard there, and he could have reached Gettysburg in an hour and a half. A second and still more urgent appeal decided that commander, late in the afternoon, to set his troops in motion. It was then too late. Sickles, who might have been at Gettysburg inside of three hours with the greater part of his corps, appears to have lingered in a deplorable state of indecision until between two and three o'clock in the afternoon, before he could make up his mind what to do. It was then too late.[40]

By contrast we find Ewell promptly going to Hill's assistance upon a simple request for such coöperation, though Ewell was Hill's senior;[72] and we further find that his doing so proved the turning-point of this very battle.

Union Positions, July 1, 3 P.M.

Was there a want of cordiality between the Union commanders? Was it really culpable negligence, or was there only incapacity?

While, therefore, one corps certainly, two probably, might easily have got to the field in season to take a decisive part in the battle, but[73] remained inactive, the Confederates were hurrying every available man forward to the point of danger. This was precisely where Reynolds' fall proved supremely disastrous, and where an opportunity to acquire a decisive superiority on the field of battle was most unfortunately thrown away for want of a head.[41]

The Union line, lengthened out by the arrival of the Eleventh Corps, had now been carried in a quarter circle around Gettysburg, or from the Hagerstown road on the left to near Rock Creek on the right, the Eleventh Corps being deployed across the open fields extending from the Mummasburg to the Harrisburg road, with Barlow's division on the extreme right. When this corps formed front in line of battle, there was a gap of a quarter of a mile left wide open between it and the First Corps. Furthermore, it was drawn up on open ground which, if not actually level, is freely overlooked by all the surrounding heights.

That this corps was badly posted was demonstrated after a very brief trial.

Having got into line facing southward, Rodes[74] began his advance against the right of the First Corps and left of the Eleventh shortly before three o'clock, supported by a tremendous artillery fire from Oak Hill. Our troops stood firm against this new onslaught. It was only fairly under way, however, when Heth and Pender joined in the attack.

The fighting now begun was on both sides of the most determined character.

On his side, Rodes was quick to take advantage of the break existing between the two Union corps, and promptly pushed his soldiers into it; but they were not to get possession so easily, for Doubleday now ordered up his last division to stem the tide surging in upon his uncovered flank. These troops gallantly rushed into the breach, where a murderous contest began at close quarters, with the result that, failing to close up the gap, the division was finally drawn around the point of the ridge, where the Mummasburg road descends into the plain, so forming a natural bastion from which the Union soldiers now drove back their assailants with great slaughter. Many of Iverson's brigade were[75] literally lying dead in their ranks after this repulse.

In front of Meredith, who still held the wood, and Stone's "Bucktails," who lay at their right, "no rebel crossed the run for one hour and lived." Beyond them Biddle was still holding his own at the left, though his ranks were fast thinning. On both sides the losses were enormous. In twenty-five minutes Heth had lost two thousand seven hundred out of seven thousand men. This division having been fought out, Pender's was brought up, the artillery redoubled its fire, Rodes pushed his five brigades forward again, and a general advance of comparatively fresh troops was begun all along the line.

But it was on the right that disaster first fell with crushing force.

Here Rodes' assault on the left of the Eleventh Corps met stout resistance. But while the troops here were fighting or shifting positions to repel Rodes' rapid blows, Early's division was seen advancing down the Harrisburg road against the right, which it almost immediately struck. Thus reinforced and connected,[76] not quite one-half of Lee's whole army was now closing in around two-sevenths of the Union army.

Obstinate fighting now took place all along the line. The First Corps held out some time longer against repeated assaults, losing men fast, but also inflicting terrible punishment upon their assailants, Rodes alone losing two thousand five hundred men before he could carry the positions before him. The Confederate veterans, though not used to praising their opponents, freely said that the First Union Corps did the fiercest fighting on this day of which they ever had any experience.

But Early's attack on the right, though sternly resisted by Barlow, proved the last straw in this case. The right division being rolled back in disorder by an assault made both in front and flank, the left also gave way in its turn, and soon the whole corps was in full retreat across the fields to the town, which the exultant enemy entered along with them, picking up a great many prisoners on the way or in the streets, notwithstanding a brigade of the reserve came down from Cemetery Hill to check the pursuit.

The Eleventh Corps being thus swept away, the[77] First fell back rather forsaken than defeated, a few regiments on the left making a final stand at the seminary to enable those on the right to shake off their pursuers. But at last the winding lines came down from Seminary Ridge into the plain. Buford's cavalry again came to the rescue in this part of the field, riding with drawn sabres between pursuers and pursued, so that the Confederates hastily formed some squares to repel a charge, while the wreck of the Union line, disdaining to run, doggedly fell back toward the town, halting now and then to turn and fire a parting volley or rally its stragglers round their colors. It was not hard pushed except at the extreme right, where some of Robinson's division fell into the enemy's hands; nor did resistance cease until its decimated battalions again closed up their ranks on the brow of Cemetery Hill—noble relic of one of the hardest-fought battles of this war. Of the eight thousand two hundred men who had gone into action in the morning, five thousand seven hundred and fifty had been left on the blood-dyed summit of Oak Ridge, or in the enemy's hands. The[78] losses were frightful. In one brigade alone, one thousand two hundred and three men had fallen. In all, the losses more than equalled half the effective strength.

The Eleventh Corps also lost heavily, though mostly in prisoners. In both corps ten thousand soldiers were missing at roll-call.

Early's soldiers were now swarming about Gettysburg in great spirits. Hays' brigade alone entered the town, Avery going into a field on the East, and the others out on the York road. Rodes presently came up at the west, much disordered from his pursuit of Robinson. These Confederates then set about re-forming their shattered ranks, under the fire of the Union artillery from Cemetery Hill and of the sharp-shooters posted in the houses along its slopes. This fire became so galling that the enemy's infantry were obliged to get under cover of the nearest ridges or houses. In this way Ewell's Corps came to be planted nearest the approaches to Cemetery Hill.

Heth and Pender did not advance beyond Seminary Ridge. They had had fighting enough for[79] one day.[42] Lee was also there examining the new Union position through his glass. Notwithstanding the general elation visible about him, the victory did not seem quite complete to Lee so long as the Federals still maintained their defiant attitude at the Cemetery. There was evidently more, and perhaps harder, work ahead.

There is no evading the plain, if unwelcome, truth that this battle had been lost, and two corps of the Union army nearly destroyed, for want of a little more decision when decision was most urgently called for, and a little more energy when activity was all-important. The fate of most great battles has been decided by an hour or two, more or less. Two of indecision decided this one.

FOOTNOTES:

[33] Buford's information was quite exact. "June 30, 10.30 P.M. I am satisfied that A. P. Hill's corps is massed just back of Cashtown, about nine miles from this place. Pender's division of this corps came up to-day, of which I advised you. The enemy's pickets, infantry and artillery, are within four miles of this place, at the Cashtown road."—Buford to Reynolds.

[34] Colonel Chapman Biddle puts the Confederate force in camp around Cashtown or Heidlersburg, each eight miles from Oak Ridge, at thirty-five thousand of all arms; perhaps rather an over-estimate of this careful writer.

[35] His horse carried him a short distance onward before he fell. His[80] body was carried to the rear, in a blanket, just as Archer was being brought in a prisoner.

[36] When attacked in this way a battery is at the mercy of its assailants.

[37] General Abner Doubleday succeeded to the command of the First Corps on Reynolds' death.

[38] The First Corps finally held a line of about a mile and a half, from the Hagerstown to the Mummasburg road.

[39] The head of this corps arrived at about 12.45 and the rear at 1.45 P.M. It would take not less than an hour to get it into position from a half to three-fourths of a mile out of Gettysburg.

[40] It is a well-settled principle of war as well as of common sense that a corps commander may disregard his orders whenever their literal execution would be in his opinion unwarranted by conditions unknown to, or unforeseen by, the general in command of the army when he issued them. This refers, of course, to an officer exercising a separate command, and not when in the presence of his superior.

[41] The positions of the several corps that afternoon were as follows, except the First and Eleventh: Second at Taneytown, Third at Emmettsburg, Fifth at Hanover, Sixth at Manchester, and Twelfth at Two Taverns.

[42] Heth, Rodes, and Early admit a loss of five thousand eight hundred without counting prisoners. The prisoners taken by the First Corps would swell this number to about eight thousand.

VI

CEMETERY HILL

We have seen Lee arriving on the field his troops had carried just as ours were streaming over Cemetery Hill in his plain sight. Seeing Ewell already established within gunshot of this hill, Lee wished him to push on after the fugitives, seize Cemetery Hill, and so reap all the fruits of the victory just won.

Ewell hesitated, and the golden opportunity slipped through Lee's fingers. At four o'clock he would have met with little resistance: at six it was different.