WAR PAPER No. 17.

MICHIGAN COMMANDERY,

LOYAL LEGION.

THE BATTLE of ALLATOONA.

OCTOBER 5th, 1864.

A PAPER

READ BEFORE THE

MICHIGAN COMMANDERY

OF THE

MILITARY ORDER OF THE LOYAL LEGION OF THE U. S.

BY

WILLIAM LUDLOW,

Major Corps of Engineers; Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel U. S. A.

AT

Detroit, April, 2d, 1891.

Detroit, Mich.:

WINN & HAMMOND, PRINTERS AND BINDERS.

1891.

ALLATOONA.

Companions and Gentlemen:

It appears strange to me that an action which all who mention it—and they are many—agree in characterizing as one of the most brilliant exploits of a war as thickset with deeds of gallantry as a rose bush with its blossoms, should not long since have had its adequate historian and monographer.

The contest was so famous, the issue so glorious, the recollection of the day still must be so vivid in the minds of the survivors, that I could not anticipate any lack of material wherefrom to procure data to formulate a reasonably satisfactory narrative of such a gallant feat of arms, and in such detail as to give it life and color. But of all the war papers that have been written on affairs great and small, none that I know has had Allatoona for its special subject, and from the sources of information at my command, I have found it quite impracticable to construct an account that is not in some respect at variance with others made by authority. The official reports, while giving the general features, of necessity exclude most of the minor but equally interesting details, and the omissions, inaccuracies and discrepancies, not important in some particulars and material in others, for the purposes, at least, of a fully detailed and authenticated[Pg 4] narrative, cannot at this time be corrected. And even the numbers engaged on each side, and of those who fell as victims, are not known with certainty.

This paper, therefore, can pretend to be no more than an outline sketch, which an abler hand must put itself to filling out and completing. When the war records shall have been made fully public, as they will be presently, and at least all the official material be available, the historian of Allatoona, by extended research and correspondence with survivors, should address himself to the task of preparing an authoritative narration in order to preserve to posterity the record of a memorable and typically American event.

For an event it was; a vital one, as it would appear, to the full success of Sherman’s campaign, and with the “March to the Sea” hung in the balance and awaiting the issue.

The importance of a given moment in the world’s history is not of necessity to be estimated by the numbers occupying the stage at the time, nor even with the degree of activity or turmoil with which their parts are playing.

Much labor is wasted in the lives of men, and mountains of effort result often in mere noise or discomfiture, making no real history. The center of gravity of two worlds may be an immaterial point, and the earth itself revolves upon a slender axis. So a turning point of history may be concentrated upon a comparatively narrow field, while the reverberation of its potency shall resound forever, as the silent nod of Jove lets loose the thunders of Olympus to shake the earth and change the fate of nations.

Some preliminary remarks are in order, explanatory of the general situation and its relation to the Battle of Allatoona.

THE GENERAL SITUATION.

It was the fall of ’64. The fiery comet of secession that, blazing out in ’61, for three long years had scorched the firmament, spreading death and pestilence over all the land, was waning in its course; doomed presently to disappear forever in Chaos, but emitting malignant emanations to its latest spark. The structure of the Confederate Government, practically a military despotism, founded on the enforced servitude and sale of human beings, reared and upheld by the lives, the fortunes, and the constrained or misguided energies of a deluded and chivalrous people, to feed the vain ambition of an oligarchy, was toppling to the ruin that six months later overwhelmed it. Great was to be the fall thereof, and not even to-day is the atmosphere fully cleared of the dust of its destruction.

Two famous, and as the outcome proved, morally conclusive campaigns had been fought and closed.

In the East, Grant, moving against Richmond through the wilderness and swamps of Virginia, all the long summer had been dealing trip-hammer blows, as deadly and sickening to his foe as the stroke of the axe in the shambles, and at length resting from the slaughter, lay before Petersburg and astride the James; feeling out with his left to cut Lee’s lines of communication to the South and West, and pressing him close that he should not detach any of his force to act against Sherman.

In the West, Sherman, starting from Chattanooga, with an antagonist the wariest, wisest and most skillful captain of the rebel host to oppose him, had overreached his foe at every point, and stretching out his sinewy arm, had seized in a relentless grasp the “Gate City” of the South; and [Pg 6]electrified the country with the exultant shout, “Atlanta is ours and fairly won;” opening wide the door into the hollow trunk of the Confederacy and exposing its emptiness.

Of this campaign Halleck wrote: “I do not hesitate to say that it has been the most brilliant of the war,” and Grant himself, with that mutual magnanimity that characterized the two great friends and competitors for fame, declared to Sherman, “You have accomplished the most gigantic undertaking given to any general in this war, and with a skill and ability that will be acknowledged in history as unsurpassed, if not unequalled.”

But much remained.

The dragon of rebellion, though sorely smitten, still lay writhing and would not die until his time was fully come.

Lee, sullen and desperate, lay within the still invincible intrenchments of Richmond, nursing his wounds, but with power able yet to strike a heavy blow, and gathering his remaining strength for the final effort.

Sherman’s antagonists, though demoralized and bewildered, were still unconquered; and forced out from Atlanta, filled the open country with an angry buzzing, as of an overturned hive. To add to their discomfiture, the astute Johnston, the most intellectual soldier of the Confederacy, whose stubborn dispute of every inch of territory, perfect skill in defending his successive positions, and marvelous success in withdrawing without loss at the latest moment, displayed a capacity second only to that of his opponent, and whose patient policy of drawing Sherman after him, to a constantly increasing distance from his base, without himself risking the disaster of a defeat, was, as history has proved, the last crutch of the Rebellion,—had been plucked from his command by the narrow-minded Confederate President and replaced by Hood, whose fighting qualities had been proved[Pg 7] on many a field of battle, but who otherwise lacked every requisite for leadership in such a contest.

But a thousand long miles still separated Atlanta from Richmond; and these must be traversed before that proximate conjunction of forces could take place that was needed to give rebellion its coup de grace, and to tear forever from the free sky of America the fluttering and ragged emblem of a maleficent and arrogant domination.

Sherman, in Atlanta, was resting, granting well-earned furloughs to his veterans, recruiting his ranks, guarding from the cavalry, who swarmed in his rear and sought to break it, the extended line—over 250 miles—of railroad from Nashville to Chattanooga, and thence to Atlanta, upon which he depended for his supplies, and incessantly planning his next move, which he had already determined would be to the Sea, with Savannah as an intermediate base for the farther march to the rear of Lee’s Army, and a conjunction with Grant;—upon whom, in his correspondence, he repeatedly urged assent to his proposal, and suggested the capture of Savannah by the Eastern forces in advance of his own arrival there.

The Washington authorities, always timorous and vacillating, were not yet brought to assent to this superb strategic project, based upon the military theorem, “An Army operating offensively must maintain the offensive,” and constructed with Sherman’s solid judgment that he must go onward, since to withdraw would be to lose all the morale of his success up to that point.

Even Grant, with all his confidence in and reliance upon Sherman, expressed unwillingness that he should embark upon it while Hood’s Army was still undestroyed.

Meanwhile, Sherman, in full conviction that the necessity would presently be demonstrated, was watching Hood, who[Pg 8] lay some thirty miles to the Southeast of Atlanta, and whose intentions he could not even guess at,—and with tremendous energy was endeavoring to accumulate supplies in excess of daily needs, in order that when the time was ripe he should be ready to start.

GRAND TACTICS.

On his zigzag way South, early in June, with Atlanta as his then objective point, Sherman, with that wonderful mental vision of the whole horizon that characterized him, seeking for a depot where supplies could safely be accumulated, near enough at hand to be of ready access, but sufficiently removed from the scene of actual conflict to be secure from casual attack, had selected the famous Allatoona Pass, and directed that it be “prepared for defense as a secondary base.”

The place was well chosen.

The diminishing extension of the Great Smoky Mountains stretches across the Northern end of Georgia, from Northeast to Southwest.

The Range is traversed at Allatoona Pass by the Etowah River, flowing West and North to unite at Rome, thirty miles distant, with the Oostenaula and form the Coosa. The railway, coming down from Kingston,—whence a branch ran Westward to Rome,—and crossing the Etowah, winds Southeasterly among the hills, and at Allatoona station, about four miles from the river, penetrates a minor ridge and emerges from a cut some sixty-five feet in depth. It was at this point—referred to by Sherman as a “Natural Fortress”—that the “secondary base” was established, and the surplus supplies were accumulated.

The advantages for defence were admirable. The entire region is hilly and heavily timbered, rolling off to the Southward[Pg 9] to a less rugged country, and from the Heights of Allatoona looking Southeasterly, down the line of railway towards Atlanta, are visible ten to fifteen miles away, the noble, isolated masses of Kenesaw, Lost Mountain and Pine Mountain, which, raising their wooded crests high above the neighboring forest, command a wide prospect towards every quarter. The narrow ridge cut by the railway is abruptly terminated to the Northeast by the valley of Allatoona Creek, crooking among the hills to join the Etowah, and its slopes facing Northwest and Southeast are steep and difficult. Towards the West and Southwest the descent is more gradual, and a country road follows the rolling crest of the ridge along which from the Westward the main attack was ultimately to be made.

The storehouses for the supplies stood near the railway station and were fully commanded from the dominant elevations rising immediately behind them. Upon these elevations the defensive works were located by Colonel Poe, the Chief Engineer of Sherman’s army. Their plan was in conformity with the requirements of the ground and of the service to be expected of them, and while the actual construction by the troops left somewhat to be desired, and could have been bettered had Poe been able to supervise the completion of his work, when it came to the test, well did they serve their purpose. The main features were two Redoubts, about 1000 feet apart at easy supporting distance, one on each side of the railway cut, with ditches and outlying intrenchments near at hand covering the approaches, and overlooking the storehouses for the defence of which they were built.

Near the close of September, Sherman, in Atlanta, was roused by indications of activity on the part of Hood, who[Pg 10] had sent his cavalry North across the Chattahooche and into Tennessee, and had moved his infantry to a more Westerly camp; thus leaving the Savannah road open to Sherman, had he seen fit to take it.

Habitually sensitive as to his railway base, Sherman surmised that Hood’s intention was to move round him to threaten his rear. September 24th he telegraphed Howard, “I have no doubt Hood has resolved to throw himself on our flanks to prevent our accumulating stores, etc.,” and September 25th to Halleck, “Hood seems to be moving as it were to the Alabama line, leaving open to me the road to Macon as also to Augusta, but his cavalry is busy on our roads.”

He therefore reinforced the detachments guarding the numerous railway stations and bridges, sent a division of the 4th corps and one of the 14th Northward to strengthen Chattanooga, and put Thomas in command there, and thence back to Nashville to guard against Forrest, the noted rebel cavalry leader, who was ravaging Tennessee and capturing gunboats with horsemen.

Corse’s division of the 15th corps was sent to occupy Rome on the extreme Western flank, with instructions to complete the defensive works and hold it against all comers; meanwhile observing closely any movement of the enemy in his vicinity.

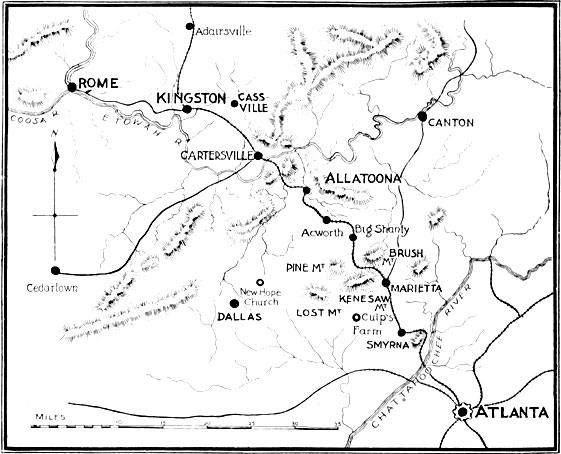

A glance at the map is desirable for the better understanding of the immediately ensuing events.

From Atlanta to Allatoona, near the railway crossing of the Etowah, is, as the crow flies, 32 miles Northwest by West. From Allatoona to Rome is 30 miles W. N. W. Thirteen miles from Allatoona towards Atlanta is Kenesaw, the railway sweeping round its North and East flanks. Fifteen miles West by South from Kenesaw, and the same [Pg 11]distance Southwest from Allatoona, is Dallas, in the vicinity of New Hope Church, where had been three days of heavy fighting late in May. Rome again is equi-distant from Dallas and from Allatoona 30 miles. The central position of Allatoona is evident; and it will also be seen that a force at Dallas occupied, in a sense, a strategic point, whence a rapid movement could be made either upon Allatoona or Rome, with the West and Southwest to fall back upon in case of need.

ALLATOONA AND VICINITY.

By October 1st, the ambiguity as to Hood’s plans was in part relieved. It was at least certain that he had crossed from the South to the North bank of the Chattahooche, although it was impossible to surmise whether he intended to make a direct attack on the railroad or to undertake an invasion of Tennessee from the Westward. In any case it behooved Sherman to bestir himself, and promptly, too. It was absolutely necessary to keep Hood’s army off the railroad, so long as the question of cutting loose for Savannah remained undecided, and at Allatoona was stored an accumulation of nearly three millions of rations of bread, the loss of which, with the railway endangered, would be a serious blow, and one possibly fatal to Sherman’s cherished project. Leaving, therefore, the 20th corps in Atlanta, to hold it and to guard the bridges across the Chattahooche above and below the railway bridge, Sherman put the rest of his forces in rapid motion Northward towards Kenesaw, 20 miles distant, and October 1st telegraphed Corse at Rome that Hood was across the river and might attack the road at Allatoona or near Cassville, on the North side of the Etowah, about midway between Rome and Allatoona. If Hood went to Cassville, Corse was to remain at Rome and hold it fast; if to Allatoona, Corse was to move down at once and occupy Allatoona, joining forces with troops in the vicinity for its[Pg 12] defence, while Sherman co-operated from the South. Repeated dispatches were sent to Allatoona, directing the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Tourtellotte, to hold the place at all hazards, and that relief would be speedy. These have been paraphrased into “Hold the Fort, for I am coming,” which, set to an inspiring air, caught the ear of the country, and is still in active service.

Sherman crossed the Chattahooche October 3rd and 4th, and finding his wires cut North of Marietta, signaled to the station on Kenesaw and thence to Allatoona, over the heads of the enemy, a dispatch to be telegraphed to Corse at Rome to move at once with all speed and with his entire command to the relief of Allatoona. Sherman himself reached Kenesaw early on the morning of the 5th, and from the summit, to use his own language, “had a superb view of the vast panorama to the North and West. To the Southwest, about Dallas and Lost Mountain, could be seen the smoke of camp fires indicating the presence of a large force of the enemy, and the whole line of railroad from Big Shanty up to Allatoona (full fifteen miles), was plainly marked by the fires of the burning railroad. We could plainly see the smoke of battle about Allatoona and hear the faint reverberation of the cannon.”

The fact was disclosed that Hood lay in force near Dallas, 15 miles to the West and South of Kenesaw, and had detached a heavy column Eastward to destroy the railroad and capture the scattered garrisons including the all-important post of Allatoona.

About 8:30 a. m. Allatoona signalled Kenesaw, “Corse is here with one brigade; where is Sherman?” As received at Kenesaw this message read, “Corse is here with ——.” My recollection is that while the signal officer was working his flag it was cut from his hands by a fragment of shell, [Pg 13]interrupting the message, the latter part of which was not received, or at least not recognized. I find, however, no official confirmation of this. The mutilated report gave Sherman immense relief, but left him to suppose that Corse had arrived with his entire division. Had he known that the reinforcement was only a portion of one brigade, his satisfaction would have been less. As he says himself, “I watched with painful suspense the indications of the battle raging there, * * * but about 2 p. m. I noticed with satisfaction that the smoke of battle about Allatoona grew less and less, and ceased altogether about 4 p. m. * * * Later in the afternoon the signal flag announced the welcome tidings that the attack had been fairly repulsed.”

The signal officer at Kenesaw reports that Sherman at the time, pronounced these signal messages “Worth a million dollars.”

CORSE.

Leaving now this bird’s eye view of what was happening, let us go back a little and follow Corse’s movements. He had arrived at Rome from Atlanta September 27th, with two of his brigades, the third being already there,—and thereafter had been busy, in accordance with his general instructions and frequent communications from Sherman, in organizing and equipping his command for the special work entrusted to him, which was in effect to reconstruct and perfect the earthworks and defences, so as to make Rome impregnable to assault, and at the same time to act as a corps of observation, constantly feeling out for and spying after the enemy, and ready, should occasion offer, to strike a heavy blow in any direction where he should be discovered.

It was isolated, difficult and responsible service, and a dangerous one, since the first contact might be with Hood’s[Pg 14] whole strength, but of the very first importance to Sherman, whose ignorance of Hood’s schemes and inability to anticipate his movements, perplexed and harassed him, and upon Corse he mainly relied to discover, by any or all means, the movements and presence of the enemy.

Corse was well equipped for such service. He had acted as inspector on Sherman’s staff, and stood high with his chief, both in personal regard and professional estimation. Of medium height, erect, active and alert, ambitious, combative, decided, of sound judgment and indomitable courage, the task of holding Allatoona could have fallen into no better hands. As Grant, giving over a page of his memoirs to mention of the battle, says of him, “Corse was a man who would never surrender.”

On the third of October Sherman sent him a warning to be wary, that Hood was meditating some plan on a large scale, and at noon of the 4th Corse received the message already mentioned, by signal from Vining’s to Kenesaw, thence to Allatoona, and thence by wire to Rome, summoning him instantly to the rescue of the threatened garrison. Corse had fortunately already telegraphed to Kingston that cars be sent him. The train in moving to Rome was partly derailed, but the single engine and about twenty cars were ready by dark.

On these was loaded a portion of one of his brigades under command of Colonel Rowett, viz; Eight companies, 39th Iowa, 280 men, Lieut.-Colonel Redfield, commanding; 9 companies, 7th Illinois, 291 men, Lieut.-Colonel Perrin, commanding; 8 companies, 50th Illinois, 267 men. Lieut.-Colonel Hanna commanding; 2 companies, 57th Illinois, 61 men, Captain Van Stienberg, commanding; detachment of the 12th Illinois, 155 men, Captain Koehler, commanding, making a total of 1,054 men, which, with the ammunition for the [Pg 15]division, was all that the available transportation could accommodate. The train left Rome at 8:30 p. m., and reached Allatoona a little after midnight. The troops were debarked, the ammunition unloaded with all speed, and the train immediately started back to Rome for another cargo of troops. As it happened, in returning, possibly with undue haste, considering the rough and insecure condition of the track and roadbed, the train was again derailed, and in consequence no further reinforcements reached Allatoona until about 8 p. m. of the 5th,—four hours after the battle was over.

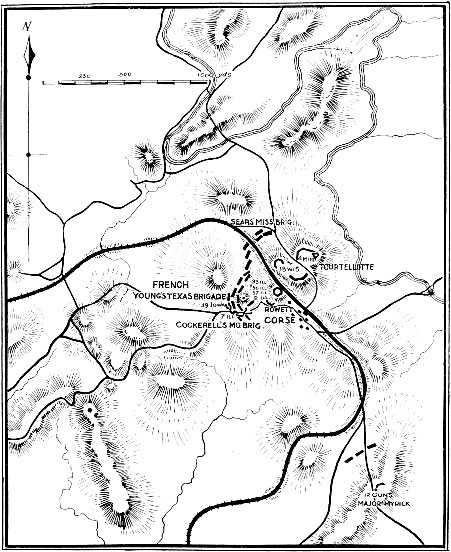

SKETCH OF THE BATTLEFIELD.

Corse immediately took command, and after a rapid survey of the field with Tourtellotte, in the quiet of the starlit night, proceeded to make his dispositions for defence.

THE DEFENCES OF ALLATOONA.

Allatoona was garrisoned as follows: Ten companies, 4th Minnesota, 450 men (of whom 185 were recent recruits), Major Edson, commanding; 10 companies, 93rd Illinois, 290 men, Major Fisher, commanding; 7 companies, 18th Wisconsin, 150 men, Lieut.-Colonel Jackson, commanding, a total of 890 men, organized as a brigade, with six guns of the 12th Wisconsin Battery, under Lieutenant Amsden (number of men not given), and all under the command of Lieut.-Colonel Tourtellotte of the 4th Minnesota, as earnest, brave and steadfast a man in the discharge of duty as ever drew a sword.

Prior to Corse’s arrival, the little garrison, with a full consciousness of its responsibility for the defence of the Post and of the safety of the huge accumulation of rations stored in the neighboring warehouses, warned of danger, and later stimulated to the utmost endeavor by messages from [Pg 16]Sherman, and inspired by the calm and fearless determination of its commander, had been busily preparing for the attack.

The two small redoubts, one on each side of the railway cut, have been mentioned. The Eastern one, perhaps 75 feet in diameter, stood at the extreme Eastern end of the ridge, looking into the valley of Allatoona Creek, and distant about 280 yards from the railroad and 340 yards from the Western redoubt, towards which it had an open view. Guarding the crooked crest between the railroad and redoubt were three detached lines of entrenchments, one looking Southward towards the storehouse 200 yards distant, and two guarding the Northern aspect, with flanks refused on each side of a ravine that lay between them and down which went a road to the Northward.

On the West side of the railway cut, and almost on its verge, stood the other redoubt, about 90 feet in diameter, occupying an elevation from which the ground fell in all directions. Westwardly, after a moderate dip, the ground rose again to a second elevation or spur, on which stood a house, distant from the redoubt about 170 yards. Beyond this the ground again fell, and the road ran West and Southwest, undulating with the roll of the ground. The exterior defences of the West side, in addition to the ditches surrounding the redoubt, were a short line of entrenchments near the crest Southwest of the redoubt, and a longer line of rifle-pits lying completely across the ridge, beyond the house and about 260 yards distant from the redoubt. These rifle-pits, held by the 39th Iowa and the 7th Illinois, were later the scene of one of the most savage encounters in the history of war.

About three-quarters of a mile out on the road, occupying an open elevation, were still other small works and rifle-pits, not, however, any portion of the regular defences. They had[Pg 17] low parapets and were supposed to have been constructed by Johnston’s army when it occupied the locality in June previous. It was from these outer works, which there was, of course, no serious attempt to hold, that our outposts were driven in by the arrival of French’s troops on the morning of the 5th.

Tourtellotte was made aware on the 3rd that the enemy was operating on the railroad South of him, and on the 4th was signalled by Sherman through Kenesaw that the enemy was moving upon him, and that he must hold out, but not till the evening of the 4th was any direct demonstration made on Allatoona.

Feeling the paucity of his isolated force, he had worked night and day to construct and strengthen his defences and mature his plans.

The two redoubts were well located for mutual support, each being able to take in flank an enemy assaulting the other from the North or South. The relative disadvantage of the West redoubt, irrespective of its exposure to the probable brunt of an attack, was the fact that higher elevations to the West and Southwest partly commanded it. Tourtellotte therefore built the rifle-pits across the crest of the ridge to the Westward with the object of holding off the enemy as long as possible, and if the crest were taken, of retiring to the redoubt, to reach which the enemy must cover a distance of some 220 yards without shelter. In addition, he partly enclosed the West redoubt with a stockade, at the junction of the outer slope and the surrounding ditch, to prevent escalade if the enemy should reach it, slashed such timber as remained for abattis, and collected some cotton bales with which to close the entrance.

His gunners in the East redoubt, and the infantry as well on the East side of the cut, were charged to watch the flanks[Pg 18] of the West redoubt, and direct their fire so as to cover the slopes to the North and South of it.

His garrison was depleted by his orders to maintain a force to guard the block house at the bridge across Allatoona Creek, about two miles South of the post, where three companies of the 18th Wisconsin were stationed.

They were summoned by French on his way to Allatoona to surrender, but refused, and held the block house, but as French was sullenly withdrawing after the battle, the post was heavily shelled and set on fire, and when the roof was blazing and the men suffocating with the heat and smoke, they surrendered; 4 officers and 80 men being taken prisoners. These men, though included in the return of casualties of the 18th Wisconsin, were not concerned in the Battle of Allatoona.

Tourtellotte, on the evening of the 4th, apprehending a night attack, which would impair the advantages of his position, strengthened his grand guard, barricaded as well as he might the roads to the South and West, and made arrangements to fire a house or two so as to illuminate the site of the little village and the storehouses; but about midnight was immensely relieved by the arrival of Corse, which more than doubled the strength of the garrison and made it possible to man the defences with some measure of effectiveness.

THE MORNING OF THE BATTLE.

There was but little delay in getting down to work. By 2 in the morning a rapid fire was opened on the skirmish lines South of the post, as though the enemy were pushing up the railroad straight at the stores. Tourtellotte immediately dispatched the 18th Wisconsin to reinforce the outposts in that direction, and an hour later Corse threw out a battalion of the 7th Illinois in further support. Five [Pg 19]companies of the 93rd Illinois were also sent out to the Westward near the outlying works already referred to.

At daybreak, under cover of a strong skirmish line, Corse withdrew the troops from the open ground in the vicinity of the village to the summit of the ridge, placing the 4th Minnesota and the 12th and 50th Illinois in the redoubt, and intrenchments on the East side of the railway cut, under the immediate command of Tourtellotte, and himself occupying with the rest of his force, under the immediate command of Rowett, the Western side, upon which it was evident the weight of the attack must fall. The 7th Illinois and the 39th Iowa, on the left and right respectively, facing West, were ordered to occupy the line of rifle-pits crossing the ridge about 250 yards in advance of the redoubt. As no defences intervened between this line and the ditch encompassing the redoubt itself, it was of vital importance to hold it and keep the enemy in check to the last moment, and the two regiments were instructed to maintain their position at all hazards. The event proved with what fidelity and devotion the trust was discharged.

Three companies of the 93rd Illinois were stationed in the rifle-pits adjacent to the West redoubt, and the remainder of the troops were distributed forward on skirmish and outpost duty. The six guns of the battery were equally divided, two being stationed in each redoubt, with the third outside behind a low parapet.

The day broke calm and clear, with the crisp air and bright warm sun of that superb mountain region. Sherman, on Kenesaw, takes occasion to record it as a “beautiful day” with some vague consciousness in his mind, perhaps, of the contrast between the shining peace that reigned above and the devil’s work that in smoke and fury waged below. At half-past six a rebel battery of 12 pieces opened from an elevation[Pg 20] three-quarters of a mile South and East of Allatoona, and for two hours maintained a furious cannonade, that, concentrated upon the two redoubts, filled the air with smoke and fragments of shell, and deafened the ear with almost incessant detonations. Meanwhile French’s skirmish lines were vigorously pushed round to the West and North until, with the exception of the steep and timbered valley of Allatoona Creek on the extreme East, the garrison was completely invested.

At 8:30, amid a temporary lull of the uproar that had prevailed, a flag of truce was sent in bearing the following message: It was dated

Around Allatoona, Oct. 5, 1864, 7 A. M.

Commanding Officer, U. S. Forces, Allatoona.

Sir:

I have placed the forces under my command in such position that you are surrounded, and to avoid a needless effusion of blood, I call on you to surrender your forces at once and unconditionally. Five minutes will be allowed you to decide. Should you accede to this, you will be treated in the most honorable manner as prisoners of war. I have the honor to be

Very respectfully yours,

S. G. FRENCH, Maj.-Gen’l C. S. A.

In making his report subsequently, French endorses on a copy of this summons, the following:

Maj. Sanders, the bearer of this communication, was attacked while bearing the flag of truce. He delivered the communication to an officer and told him he would wait outside the works fifteen minutes for an answer. None came; none was sent, and so the attack was made.

S. G. F., Maj.-Gen’l, Commanding.

Whatever may have been the external conditions that led to this view of the matter on the part of General French, there is no question that Corse did reply, and promptly and to the point. He wrote his answer on the top of a neighboring stump, and a splinter or two may have gotten in it:

[Pg 21]Maj.-General French, C. S. A., etc.:

Your communication demanding surrender of my command, I acknowledge receipt of, and respectfully reply that we are prepared for the ‘needless effusion of blood’ whenever it is agreeable to you.

I am very respectfully your obedient servant,

JOHN M. CORSE,

Brigadier-General, Commanding U. S. Forces.

When this reply had been dispatched, Corse remarked, “They will now be upon us,” and nothing remained but to notify the several commands of the purport of the correspondence, and to prepare for the bloody work that lay before them.

French commanded a division in the corps of Lieutenant-General Stewart, which had been dispatched by Hood Eastward from Dallas to destroy the railroad, as witnessed by Sherman from the summit of Kenesaw, and his report, dated Nov. 5, from which the following particulars of his movements are derived, is of great interest.

Stewart had struck the railroad at Big Shanty, four miles North of Kenesaw on the evening of October 3rd, and his three divisions labored all night at their task, completing it as far as Acworth. This work accomplished, French’s division was sent Northward under direct orders from Hood, which are given in French’s report, and have some peculiar features. Both orders are dated October 4th, and were handed to French at Big Shanty by Stewart at noon. The earlier one said that French “Shall move up the railroad and fill up the deep cut at Allatoona with logs, brush, dirt etc.” Also that when at Allatoona, French was, if possible, to move to the Etowah Bridge, the destruction of which would “be of great advantage to the army and the country.” The second order again urged the importance of destroying the Etowah Bridge, if such were possible, and that as the[Pg 22] enemy (Sherman), could not disturb him before the next day, he was to “get his artillery in position and then call for volunteers with ‘lightwood’ to go to the bridge and burn it.”

The curious points about these instructions are, in the first place, the absurdity of a wearied body of troops undertaking such a task as that of filling up a railway cut 65 feet deep and some 300 or 400 yards long, in the way described, with “logs and dirt” and the futility of doing it, if it were possible. It would have taken French several days to fill up that cut, even assuming him to be uninterfered with, and one day’s labor would open it again.

The second point is the absence of any reference to a garrison at Allatoona, or to the accumulation of stores there. French was a good soldier, and after stating in his report that as both he and Stewart knew the facts in the case and were aware of the large amount of stores, they considered it important that the place be captured, contents himself with saying, dryly, “It would appear, however, from these orders, that the General-in-Chief was not aware that the Pass I was sent to have filled up was fortified and garrisoned.” The fact is that it requires something more than mere courage to command an army, and it seems likely that a few such specimens of leadership cost Hood the confidence of his subordinates, and thoroughly justified Sherman in a disparaging remark he made respecting him a day or two later.

Stewart gave French 12 pieces of artillery under Major Myrick and at 3:30 P. M. of the 4th he marched away to Acworth, but was detained there until 11 at night by lack of rations. The night was dark, the roads bad, and he didn’t know the country. From Acworth he reports seeing night signalling between Kenesaw and Allatoona, and fearing that reinforcements might be sent from the Northward, he dispatched a small cavalry force to reach the railroad as close[Pg 23] to the Etowah as possible and take up the rails. It was a wise precaution, but undertaken too late, as Corse was at Allatoona by midnight. French arrived there about 3 in the morning, and, as he writes, “Nothing could be seen but one or two twinkling lights on the opposite heights and nothing was heard except the occasional interchange of shots between our advance guards and the pickets of the garrison in the valley below.” He placed his artillery in position at Moore’s, 1300 yards south and east of the Post, an admirable location for the purpose intended, having an open view of the defences across the intervening hollow, left with it the 39th North Carolina and the 32nd Texas, of Young’s brigade, as supports, and sought to gain the ridge west of the fortifications, intending to attack at daybreak, but after floundering in the Egyptian darkness of the forest, with no roads and over a rugged country, and unavailingly seeking, notwithstanding the aid of a guide, to get upon the ridge westward of the works, was compelled to wait for daylight. Finally at 7:30 the head of the column arrived about 600 yards distant from the West Redoubt, and here French got his first view of the works, which impressed him at once as much more formidable than he had anticipated. Instead of one small redoubt on each side of the railroad cut, as he had been led to believe, he declares he saw no less than three on the west side and a “Star Fort” on the east, with outworks and approaches, defended to a great distance by abattis, and nearer the forts by stockades and other obstructions. It may have been the weariness of a long night march, or perhaps the too early morning air, that conjured these formidable defences to French’s eyes, or possibly, it is the exterior aspect of these works that to a covetous and hostile apprehension enlarges their numbers and proportions.

It must be admitted that from the interior standpoint[Pg 24] they shrunk mightily from French’s description, and the defenders at least would have been hugely gratified could they have had the privilege of occupying what French thought he saw.

He rapidly made his dispositions for assault, sending Sear’s Mississippi Brigade round by the left to gain the north flank of the works, while Cockerell’s Missouri Brigade formed line across the ridge, with Young’s Texas Brigade behind it to support and follow up the attack. Myrick had been ordered to open up with his guns and continue his fire until the attacking troops were so close up to the works as to prevent it. Sears, having the longer distance to traverse, was to begin the assault when Cockerell would immediately move forward. Sears was delayed by the ruggedness of his route to the north side of the works, and in fact for a time lost his bearings among the wooded hills, and was not in position until 9 a. m. by French’s time. French says that when he sent his summons to surrender, the Federal officer entrusted with the missive was allowed 17 minutes within which to bring the answer, and this time expiring, Maj. Sanders returned without any. Nothing is said in the report as to the firing upon him, noted in the endorsement on the copy of the summons already mentioned.

THE ASSAULT.

Cockerell was at length ordered forward and the attack began. According to French’s account, everything went as successfully as possible. He represents the triple lines of intrenchments and Redoubts on the west side as being captured one, after another, his troops resting but briefly at each to gather strength and survey the work before them, and again rushing forward in murderous hand-to-hand conflict[Pg 25] that left the ditches filled with dead, until they were masters of the “Second Redoubt,” and the “Third or Main Redoubt” was filled with those driven from the captured works and further crowded by the refugees from the eastern fort and its defences, who had been driven out by the attack of Sears. He represents the Federal forces, their fire almost silenced, as being herded into the one Redoubt on the west, of which French’s troops occupied the ditch and were preparing for the final attack.

At this critical moment, with the garrison and the precious stores, as it were, in the hollow of his hand, French received word that General Sherman, who had been “repeatedly signalled during the battle,” was close behind him with his whole army, and within two miles of the road he would have to take to rejoin his corps.

On this point of Sherman’s proximity to French as his reason for leaving, we have not only full knowledge of the exact position and movement of our troops to show that such was really not the case, but a brief piece of testimony from the other side in the shape of a dispatch from Major Mason, Hood’s adjudant-general, from which it is evident that French, becoming hopeless of success, had sought in advance to justify at headquarters the failure of his enterprise. The date and hour of this dispatch, which reads as follows, are of interest:

“Carley’s House, Oct. 5, 1864. 8:15 p. m.

Lt. Gen’l Stewart,

Com’d’g Corps.

General French’s dispatch, forwarded by yourself, is just received. Gen. Hood directs me to say that he does not know where a division could march at this time to give any assistance to Gen. French, but that you will endeavor to send some scouts to him, and direct him to leave the railroad and march to the West, to New Hope Church.

Gen. Hood does not understand how Gen. French could be cut off at the point he designates in his dispatch, as he should have moved directly away from the railroad to the West, if he deemed his position precarious.

A. P. M.”

[Pg 26]It is of course obvious from the map that if French found Sherman approaching from the South, he had only to follow westward the road up which he had been charging at Allatoona all day and free himself from danger in an hour. It would be of interest to see this dispatch of French’s and observe the hour when sent, but it is not forthcoming. The hour of the reply is significant. It need not have taken a mounted man three hours to get word to Stewart, then near a junction with Hood and to Hood himself, less than 15 miles away. The reply, made at once, is written at 8:15 p. m., and French’s message must certainly have been sent later than 4 p. m. French had probably been gone from Allatoona an hour or more when he bethought him to send the request for a division to extricate him.

The facts are, that it was not until the night of Oct. 5th that the nearest troops of Sherman’s went into camp at Brushy Mountain, 11 miles distant in an air line, and none reached Allatoona until the 7th.

But to return to French. It was really an immense pity that he should feel obliged to leave just when he had but to put forth his hand to snatch the prize; but then it would not do to have his division cut off from the army, and on the whole it might be well to start, and if so, why not at once?

So about 1:30 he says an order was sent to Sears and Cockerell to withdraw. The ground was too rough to carry badly wounded men over it, so that those who could not get away on their own feet had to be left.

The artillery, unable to operate effectively with the assaulting column close up on the works, had already been in part ordered to take the road, and after the assaulting troops had left, French went to the two regiments who had supported it, and sent a battery to the block house at the railway crossing of Allatoona Creek, fired fifty shots at it, knocked it about[Pg 27] the ears of the garrison, and setting fire to it, smoked them out and marched them off as prisoners.

French’s report of this affair, written a month later, from which the above is condensed, is very interesting and dramatic, and regarded as a literary composition, of no mean merit. He has certainly made the best of a bad business, and if his facts do not quite tally with those of his opponents, at least the discrepancies were not officially noticed at headquarters, nor probably would a gloomier account of the affair have been considered more inspiriting. Those rations would have been extremely convenient, could they, or even a part of them, have been hauled away for distribution among the hungry Confederates, and if that were impracticable, it would have been at least a noble stroke to have destroyed them. On this head French’s report is silent; nor does he endeavor to explain how it happened that so vital a part of his own program was omitted. In effect, the play had been badly broken up by the attentions of the gallery, and Hamlet had slipped out of it.

French is without excuse for his fear of Sherman’s approach, baseless as we know it to have been. Armstrong is responsible for despatches to him suggesting it. All the same, the evidence is conclusive that French was beaten, that he knew it, and that he had to withdraw quite independently of Sherman’s movements.

A Confederate historian, K. S. Bevier, writes as follows on this point: “The men of French’s Division had now become so much scattered that it was impossible to gather a sufficient number to give any hope of successful assault on the Fort.”

What can wholly be pardoned to French is the unstinted commendation he bestows on the gallantry of his men.

These poor fellows, ragged and hungry, with but a handful or two of parched corn in their haversacks, had marched[Pg 28] all day on the 3rd; had worked all that night destroying the railroad; had worked and marched all day on the 4th; had marched to Allatoona during that night, and had fought nearly all day on the 5th. Nor is it forbidden to those who felt the vigor of their dashing onset and the undaunted determination with which they rallied again and again to the assault of the intrenchments, or who witnessed the hand-to-hand encounters with sword and bayonet, with butts of guns, and even with loose pieces of rock, to appreciate the intrepidity and resolution with which they hung to their bloody and fruitless task.

Brave men may honor bravery the world over. We can in all sympathy and common brotherhood say: “They were of our blood and race. Peace to their ashes. Give us the like to stand side by side with us, and we could fear no quarrel, were it with the whole round world.”

THE DEFENCE.

Having glanced at the situation from French’s standpoint, let us step over to the other side, as we may safely do at this lapse of time, and see how it actually fared with the beleaguered garrison which we left in momentary expectation of attack; and since General French has been heard, it is no more than fair to quote from the graphic reports of the federal commander.

After narrating his preliminary movements, and the stations of the troops, he proceeds:

“I directed Col. Rowett to hold the spur on which the 39th Iowa and 7th Illinois were formed, * * * and taking two companies of the 93rd Illinois down a spur parallel with the railroad and along the bank of the cut, so disposed them as to hold the north side as long as possible. Three companies of the 93rd, which had been driven from the west end of the ridge, were distributed in the ditch South of the Redoubt, with instructions to keep the town well covered by[Pg 29] their fire, and to watch the depot where the rations were stored. The remaining battalion of the 93rd, under Major Fisher, lay between the Redoubt and Rowett’s line, ready to reinforce wherever most needed.

“I had barely issued the orders when the storm broke in all its fury on the 39th Iowa and 7th Illinois. Young’s Brigade of Texans had gained the west end of the ridge and moved with great impetuosity along its crest till they struck Rowett’s command, when they received a severe check, but undaunted came again and again. Rowett, reinforced by the gallant Redfield, encouraged me to hope we were safe here, when I observed General Sears’ brigade moving from the North, its left extending across the railroad (opposite Tourtellotte). I rushed to the two companies of the 93rd Illinois, which were on the brink of the cut running north from the Redoubt, they having been reinforced by the retreating pickets, and urged them to hold on to the spur; but it was of no avail; the enemy’s line of battle swept us back like so much chaff, and struck the 39th Iowa in flank, threatening to engulf our little band without further ado. Fortunately for us, Col. Tourtellotte’s fire caught Sears in flank, and broke him so badly as to enable me to get a staff officer over the cut with orders to bring the 50th Illinois over to reinforce Rowett, who had lost very heavily. However, before the regiment sent for could arrive, Sears and Young both rallied, and made their assaults in front and on the flank with so much vigor and in such force as to break Rowett’s line, and had not the 39th Iowa fought with the desperation it did, I never would have been able to get a man back inside the Redoubt; as it was, their hand-to-hand conflict and stubborn stand broke the enemy to that extent that he must stop and reform before undertaking the assault on the fort. Under cover of the blows they gave the enemy, the 7th and 93rd Illinois, and what remained of the 39th Iowa, fell back into the fort.

“The fighting up to this time—about 11 a. m.—was of the most extraordinary character. Attacked from the north, from the west and from the south, these three regiments—39th Iowa and 7th and 93rd Illinois—held Young’s and a portion of Sears’ and Cockerell’s brigades at bay for nearly two hours and a half. The gallant Col. Redfield, of the 39th Iowa, fell, shot in four places, and the extraordinary valor of the men and officers of this regiment, and of the 7th Illinois, saved to us Allatoona.

“So completely disorganized were the enemy, that no regular assault could be made on the fort till I had the trenches all filled and the parapets lined with men. The 12th and 50th Illinois arriving from the east hill, enabled us to occupy every foot of trench, and keep up a line of fire that, as long as our ammunition lasted, would render our little fort impregnable. The broken pieces of the enemy enabled them to fill every hollow and take every advantage of the rough ground surrounding the fort, filling every hole and trench, seeking shelter behind every[Pg 30] stump and log that lay within musket range of the fort. We received their fire from the north, south and west of the Redoubt, completely enfilading our ditches, and rendering it almost impracticable for a man to expose his person above the parapet. An effort was made to carry our works by assault, but the battery (12th Wisconsin) was so ably manned and so gallantly fought as to render it impossible for a column to live within one hundred yards of the work. Officers labored constantly to stimulate the men to exertions, and almost all that were killed or wounded in the fort met their fate while trying to get the men to expose themselves above the parapet and nobly setting them the example.

“The enemy kept up a constant and intense fire, gradually closing around us and rapidly filling our little fort with the dead or dying. About 1 p. m. I was wounded by a rifle ball that rendered me insensible for some thirty or forty minutes, but managed to rally on hearing some persons cry, ‘Cease firing,’ which conveyed to me the impression that they were trying to surrender the fort.

“Again I urged my staff, the few officers left unhurt, and the men around me, to renewed exertions, assuring them that Sherman would soon be there with reinforcements. The gallant fellows struggled to keep their heads above the ditch and parapet in face of the murderous fire of the enemy, now concentrated upon us. The artillery was silent, and a brave fellow, whose name I regret having forgotten, volunteered to cross the railway cut which was under fire of the enemy and go to the fort on the east hill to procure ammunition. Having executed his mission successfully, he returned in a short time with an arm load of canister and case shot. About 2:30 p. m. the enemy were observed massing a force behind a small house and the ridge on which the house was located distant northwest from the fort about 150 yards. The dead and wounded were moved aside so as to enable us to move a piece of artillery to an embrasure commanding the house and ridge. A few shots from the gun threw the enemy’s column into great confusion, which being observed by our men, caused them to rush to the parapet and open such a heavy and continuous musketry fire that it was impossible for the enemy to rally. From this time until near 4 p. m. we had the advantage of the enemy, and maintained it with such success that they were driven from every position and finally fled in confusion, leaving their dead and wounded, and our little garrison in possession of the field.

“The hill east of the cut was gallantly and successfully defended by Col. Tourtellotte, with the 4th Minnesota and a portion of the 18th Wisconsin (which was drawn from outpost duty towards the south about 10:30). * * * Col. Tourtellotte, though wounded in the early part of the action, remained with his men until the close, and rendered valuable aid in protecting my north front from the repeated attacks by Sears’ brigade.”

[Pg 31]A notable struggle truly and stirringly told, even though the limitations of an official report forbid that amplification of incident that would make as thrilling a tale as tongue could utter. From start to finish, seven solid hours of as desperate fighting as ever was done under the sky of heaven, and with multiplied acts of individual heroism that would tax the pen of Homer to narrate.

With the exception of about 250 rounds, the supply of ammunition brought from Rome for the entire Division, had been expended by a portion of a single brigade.

Every one of the subordinate commanders’ reports on both sides bears testimony to the unparalleled fierceness and concentration of the struggle, and the closeness and duration of the action, and the terrific slaughter; and these reports, it may be noted, are made by the ruggedest of Sherman’s and French’s veterans—men inured to war in every aspect, and as familiar with bloody battle-fields as we of to-day with the street we daily tread. In reading these scant records, one scarce knows whether to admire the more the daring vigor and persistence of the attack, or the spirit, valor and heroic determination of the defence. With both it was “To do or die,” and each can feel that none, save his rival, can challenge supremacy in war-like exploit.

Corse’s signal dispatch to Sherman after the fight can therefore well be excused, “I am short a cheek-bone and an ear, but able to whip all h—l yet.”

INCIDENTS OF THE BATTLE.

It is a thousand pities that the many notable incidents of this fight are not on record; but, so far as I am aware, no one has sought to gather them in any complete and authentic form.

[Pg 32]Corse caught his wound about 1 o’clock while scanning the movements and position of the enemy from the Redoubt. It was a close call for his life, the ball ploughing his cheek and splitting his ear, and, as might be imagined, dazing him. A surgeon took him in charge and ministered as well as the circumstances permitted. At intervals Corse was unconscious, but rallied from time to time, as though the spirit within him crowded itself up through the physical deadening of his senses. At one of these occasions he caught the words “Cease firing,” and as mentioned in his report, feared some attempt to surrender. On this point, in a private letter, he speaks as follows: “Do you remember our losing a large number of Springfield rifled muskets that exploded near the muzzle after becoming foul from over-shooting? I saw some that had exploded, say about the shank of the bayonet. It was so phenomenal as to make a decided impression on my mind at the time. I think a large number of these must have been lost, and when the order was given to cease firing, it was under the impression that if the men were not given a chance to clean their guns, we would lose them all and be overwhelmed. My impression, you remember, at the time was that the order to cease firing meant surrender, but Rowett removed that impression in subsequent interviews, during and after the war.”

Rowett’s order to “Cease firing” had, of course, nothing to do with the cry of “Surrender.” It is true that there were men in that Redoubt ready to surrender or to do anything else in order to get out of it alive. Happily these were few, and most of them lay prone, close under the parapet, “playing dead,” with the combatants and wounded standing and sitting upon them. If I mistake not, Corse himself, at least for a time, was holding down of these “living corpses” who preferred to endure all the pain and discomfort of his[Pg 33] position rather than get up and face the deadly music that filled the air with leaden notes. It came about this way: The Redoubt was crowded, and as bloody as a slaughter pen. In its actual construction the parapet encircled a higher elevation in the center, which had not been sufficiently excavated, so that a man standing, or in fact, lying, in the middle of the work was exposed to bullets coming in close over the parapet. It was absolutely necessary to keep room for the fighting force along the parapet, so the wounded were drawn back, and in some cases were shot over and over again. The dead were disposed of in the same way, except that as the ground became covered with them they were let lie as they fell, and were stood or sat upon by the fighters. Several of the “skulkers” lay among these, but a few were in the ranks. The slaughter had been frightful. One of our guns was disabled from the jamming of a shot, and we were out of ammunition for the other two, thereby losing both the deterrent effect upon the enemy, and the moral encouragement that the friendly roar of cannon always gives to infantry in action. I recall distinctly the fact that a regimental flagstaff on the parapet, which had been several times shot away, fell again at a critical moment towards the end of the action. There was a mad yell from our friends outside and a few cries of “Surrender” among our own people, but a brave fellow leaped to the summit of the parapet, where it did not seem possible to live for a single second, grasped the flagstaff, waved it, drove the stump into the parapet, and dropped back again unhurt. Of course nobody knows the name of that man, but his action restored confidence, and a great Yankee cheer drowned the tumult, and no cry of “Surrender” was afterwards heard.

What saved us that day—among forty other things—was the fact that we had a number of Henry rifles (16-shooters),[Pg 34] since improved and known as “Winchesters.” These were new guns in those days, and Rowett, as I remember, had held in reserve a company of an Illinois Regiment that was armed with them until a final assault should be made. When the artillery reopened, after the incident related by Corse of the man crossing the cut and coming back with an armful of case shot, this company of 16-shooters sprang to the parapet and poured out such a multiplied, rapid, and deadly fire that no men could stay in front of it, and no serious effort was thereafter made to take the fort by assault.

It is not possible, within any reasonable limits, for a paper already too long for your patience, to undertake the recital of the numerous thrilling incidents. One may be mentioned:

An artillery sergeant, whose gun was at first stationed outside the fort behind an exterior parapet, was driven in by the rush of the enemy, and his men being all killed, he had to abandon it. Wounded himself in several places, he came into the Redoubt, frothing with rage at the loss of his piece, and demanded a crew of volunteers to go out with him and get it. Notwithstanding the deadly fire, he got them, and in three minutes was back with his recovered prize with more wounds to his account. A bloodier man was never seen, but he kept at his work, loading and firing, until a musket ball passed through his neck, and he dropped dead. The same ball traversed the body of an Iowa officer, with whom I was standing further back, and then struck me with force enough to take my breath. That ball had killed two men, and I preserved it with the name and date of the battle scratched on its but slightly distorted surface.

On Tourtellotte’s side a grim war comedy was enacted. The remains of two Mississippi Regiments—the 35th and 39th of Sears’ brigade, that had charged with desperation,[Pg 35] found themselves as the surge of battle that broke upon the hill went back, lodged in a sheltered depression of the north front, whence they could move neither up nor down without concentrating upon themselves the fire of Tourtellotte’s whole front. Unable to determine what course to take, they remained where they were to think it over, and Tourtellotte, observing their embarrassment, thoughtfully sent a portion of the 4th Minnesota to their rescue and invited them to come in. One field and several line officers and 80 men with the colors of the two regiments were the reward of the Yankee courtesy.

After the fight was over we thankfully emerged from the shambles and went out to survey the field. The dead, the dying and the wounded lay everywhere. The ditches immediately outside the Redoubt were crammed with corpses. There were dead rebels within 100 feet of the work, and they were piled in stacks near the house where they had massed for the final assault which was never made, against the reopened artillery, and the rattle of the Henry rifles. But the appalling center of the tragedy was the pit in which lay the heroes of the 39th Iowa and the 7th Illinois. Such a sight probably was never before presented to the eye of heaven. There is no language to describe it. With all the glad reaction of feeling after the prolonged strain of that mortal day, and the exultant surge of victory that swelled our hearts, it was difficult to stand on the verge of that open grave without a rush of tears to the eye and a spasm of pity clutching at the throat. The trench was crowded with the dead, blue and homespun, Yank and Johnny, inextricably mingled in their last ditch. Our heroes, ordered to hold the place to the last, with supreme fidelity, had died at their posts. As the rebel line run over them, they struck up with their bayonets as the foe struck down, and rolling together in the[Pg 36] embrace of death, we found them in some cases mutually transfixed. The theme cannot be dwelt upon.

For relief, take another one, so unique in the circumstances that I doubt at times my own recollection of it. It was in the morning when French first gained the west end of the ridge. The 93rd Illinois was in the vicinity of the outworks, a quarter of a mile or so from the Redoubt. I had been reconnoitering the ground, and the rebel column charged us sharply and without warning. We ran, of course, but in passing through or rather over an old work of low relief, one of our men stooped, grabbed a brick and turned. Curiosity overcame discretion, and I had to look. He threw the brick straight as a bullet at a rebel running toward us, and if I may be believed, the brick caught the man full in the face, and he went down like a log.

One more incident, and I am done. After the battle the wounded of both sides were collected, housed and cared for. One of the surgeons invited me to come to the hospital with him, and on the way said he had a wounded woman there. I expressed surprise, and he said: “See if you can pick her out.” We went through the hospital, and I saw no woman, but passing through again on the way back, the doctor stopped at a bed where a tanned and freckled young rebel, hands and face grimy with dirt and powder, lay resting on an elbow, smoking a corn-cob pipe. The doctor inquired, “How do you feel?” and the answer was, “Pretty well, but my leg hurts like the devil.” As we turned, the doctor said, “That is the woman,” and told me that she belonged to the Missouri Brigade, had had a husband and one or two brothers in one of the regiments, and followed them to the war. When they were all killed, having no home but the regiment, she took a musket and served in the ranks. Like an actor of the old Greek dramas, war has its two masks of tragedy[Pg 37] and comedy, although it is difficult at times to determine to which the antiphonal scene belongs—so of this case. It is perhaps not proper in such a paper as this to expose or call attention to the shifts to which the Confederates were forced to fill their ranks, but the incident may be told nevertheless.

THE STORES SAVED.

The stores which had cost such heroic endeavor and expenditure of life, were saved; the stores, which, as Corse says in a private letter, “would have been such a prize as Hood in all his long and bloody career as a soldier had never secured.” This fact is due, independently of the main action, largely to the coolness and vigilance of Tourtellotte, who in addition to fighting Sears on his north front and flanking the attacks on the west Redoubt, kept his mind charged with the protection of the warehouses, even while his wound forced him to physical inaction. As has been stated, he pushed out the 18th Wisconsin to the southward to hold back the two regiments which were in front of the rebel batteries, and only withdrew them at 10:30 when the assaulting column had reached a point in front of the west Redoubt, whence it had a fire upon the rear of the outlying command. Thereafter Tourtellotte kept a wary eye out towards the stores, with men in his southern rifle pit and its vicinity constantly on guard, and cautioned to unceasing vigilance, and although several attempts were made by individuals and small parties to reach the warehouses and fire them, they died on the way and none of them ever attained their destination. We found several bodies scattered about in the vicinity, and one of them within 20 feet of the buildings, with the implements in his hand for firing them.

As to the amount of these stores, General Sherman, in his Memoirs, says there were “over a million rations of[Pg 38] bread,” probably with Corse’s report at hand, in which the number is incorrectly stated at that amount. Cox, in his “Atlanta,” gives it more accurately at “nearly three millions.” The actual figures (2,700,000) are given in a letter from Sherman to Corse in acknowledging, on October 7th, Corse’s preliminary report of the same day.

THE LOSSES.

Corse’s losses in this battle, from the full official records, were 142 killed, 352 wounded, and omitting those captured at the block house two miles away, 128 prisoners; a total loss of 622—nearly one-third his entire command.

French in his report estimates that he had killed and wounded 750, and captured 205—which, with the block house prisoners, would make a total loss inflicted on Corse of over 1000, which is over 50 per cent. too much.

French’s losses are not known. With his report he gives a tabulated list of casualties by brigades, which shows footings of 122 killed, 443 wounded and 243 missing—a total of 799. Sears, however, whose report of casualties is the only one accessible to me, reports in his brigade alone a total loss of 425—as against 351 attributed to him in French’s schedule, which is an increase of 21 per cent. Young and Cockerell must have lost at least as heavily as Sears, and having charged our line repeatedly and had several encounters at close quarters, probably more so. Allowing for these facts, it is perhaps nearer correct to increase French’s statement of loss by 25 per cent., which would make it almost exactly 1000 men. As Corse actually buried 231 rebel dead, captured 411 prisoners, well and wounded, and picked up 800 stand of arms, and as French left behind him, according to his own account, only those of his wounded who needed litters to[Pg 39] move them, we must add to the 644 rebels accounted for by Corse at least 400 or 500 wounded who got away when French left, or previously. French’s total loss could not have been much less than 1100 or 1200.

The number of troops with him cannot be determined. He gives it as “but little over 2000 men,” in which case he lost more than half his entire number, but he omits three regiments as forming no part of the assaulting column. He refers to those supporting the artillery, but these men were in the engagement, kept the 18th Wisconsin in their front, and French thanks their leader, Col. Andrews, “who commanded on the south side,” and Major Myrick, who commanded the artillery. French’s field report for Sept. 24th showed “Present for Duty” 331 officers and 2945 men; an “Effective Present” of 3626, and an “Aggregate Present” of 4347. He probably had not less than 3000 with him at Allatoona engaged in action, in which case his total loss was proportionally the same as ours, viz., about one-third.

REPORTING TO SHERMAN.

On the morning of the 7th Corse sent me down to Kenesaw to take his report to Sherman, and supplement the gaps in the information which his wound forbade elaborating. As I reached the summit of the mountain, conscious of bearing welcome and important tidings of great joy, and considering what special form Sherman’s delight might take, I found him surrounded by a group of generals and staff scanning with binoculars the long clouds of dust that, rising above the forest to the westward, betokened a great movement of troops. It was Hood en route northward. As Sherman turned and saw me, his greeting was, “Hello! How’s Corse?” I answered that he was doing very well, and Sherman glanced[Pg 40] over the report which I handed him, and inquired, “Pretty hot, wasn’t it?” and without waiting for an answer, said, “I knew it was all right when Corse got there; I’ll write him presently.” As I stood, anxiously waiting an invitation to unbosom myself of the accumulated information that it wearied me to carry, he turned back to take another look at Hood, and some one asked, “General, what do you think Hood is going to do?” Sherman replied, with an outburst of irritation, “How the devil can I tell? If it were Joe Johnston now—Johnston was a sensible man and did sensible things. Hood is a d—d fool and is liable to do anything.” This view of his antagonist is, it will be observed, paraphrased in his letter to Corse, written immediately after, into “Hood is eccentric,” but his off-hand response was substantially as I have given it.

My interview was over. Nor since that time, until this evening, have I had a chance to “unload.”

CONCLUSION.

This practically closes the sketch of Allatoona. I can only hope that it will avail to furnish some material for a proper history of that memorable affair.

Sherman published his congratulatory Special Field Orders, No. 86, dated Oct. 7th, proclaiming the vital military principle that fortified points must always be defended to the last, regardless of numbers, declaring the “effusion of blood” at Allatoona not “useless,” as the position “was and is very important to present and future operations,” and thanking Corse and Tourtellotte and their men for their determined and gallant defence.

Just how important to his future operations was the[Pg 41] successful defence of Allatoona may be judged from what followed.

October 9th Sherman telegraphed to Grant with renewed urgency that the march to Savannah must be made, and stated, to show his preparation, “We have on hand over 8000 head of cattle and three million rations of bread.”

In other words, the Allatoona stores, 2,700,000 rations, were practically all he had.

Sherman impatiently chased Hood northward, seeking to corner and devour him. But Hood, living off the country and traveling light, could go two miles to Sherman’s one, and there was no catching him. Weary of the harassing and fruitless hunt, Sherman insisted that his March to Savannah be not delayed, and on Oct. 19th to be in readiness for it, telegraphed his chief commissary at Atlanta, “Have on hand 30 days’ food.” Say, 1,800,000 rations, two-thirds of the Allatoona stores, which were supplies for 60,000 men for 45 days.

November 2nd Grant for the first time authorized the March.

Sherman abandoned Hood to his own devices, and the unhappy rebel leader, pressing northward, was heavily thrown in his encounter with Schofield at Franklin, and finally dashed himself to pieces against the “Rock of Chicamauga,” the noble George H. Thomas, lying vigilant within the defences of Nashville, and like an old lion, silently licking his chops as he watched his prey draw nigh.

November 12th Sherman, having stripped his railroad, cut the telegraph wires that no message of delay might reach him, loaded his teams, marched his 60,000 men for Savannah, and, although he “lived off the country,” got there with empty wagons.

[Pg 42]With Hood and Forrest in his rear and on his railroad, how was he to accumulate a fresh store of provision, and what would have become of the “March to the Sea” if Allatoona had been lost?

WILLIAM LUDLOW.